Notifications buzzing on my phone rarely announce good news these days. The one that grabbed my attention Wednesday afternoon was no different. While putting on my shoes to go out with a friend that ominous shudder grabbed my attention. I retrieved the device from my pocket, swiped the screen to access my e-mail inbox, and . . .

“Oh, man.”

“What?” my friend asked, her face suddenly sagging with dread. “Oh no. What?”

I read her the headline: “Jeffrey Tambor under investigation for sexual harassment by Amazon.”

“Noooo,” she yelled. “No way. Not him.”

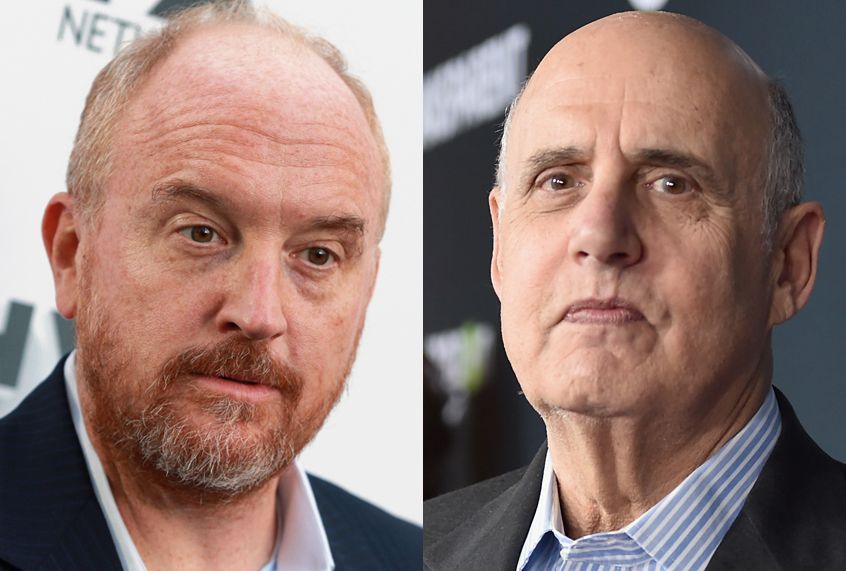

I imagine a number of people who saw that headline reacted with similar disbelief and distress largely because of the psychological dissonance between our idea of him, informed by his characters on “Arrested Development” and “Transparent,” and the accusation. George Bluth Sr., as Tambor realizes him, is a hapless, corrupt boob. Not a predator. Maura Pfefferman is a sensitive transgender woman whose emotions are easily bruised. Again, not a predator.

These are characters, and Tambor — an Emmy, Golden Globe and SAG Award winner — has made a career out of his stellar ability to convince us that he’s something he isn’t. I get that. What roils my guts is the memory of spending time with the man last spring — interviewing him on the phone for more than an hour about his memoir, “Are You Anybody?,” then moderating a live event with him the next day.

Journalists are not supposed to befriend their subjects, and certainly I can’t claim to truly know the man based on two question and answer sessions. However, my mother had passed away a short time before that interview, and although I was functioning, every day still felt like I was walking around with no skin on my body. I did not tell him this. Yet, after the last “thank you” of that phone interview he extended the conversation for another 30 minutes to share his own experiences of internalized inadequacy, loss and the grace of forgiveness.

We’d reprise some of that conversation the next day in front of an audience, where he was self-effacing and easygoing and charming, where he stayed afterward to shake hands and sign autographs. Fished out of the news cycle’s fast and dirty stream I still want to think of it as a healing experience in a year that’s flogged me — and all of us, truly — with biting sorrow and inhumanity and injustice.

This is why I don’t want to believe the allegations against Tambor, and I know that isn’t quite right.

From the viewpoint of how the American justice system is supposed to work, but often does not, we’re supposed to assume the accused is innocent until proven guilty. And Tambor vehemently insists the allegations of impropriety made by his former assistant Van Barnes in a private Facebook post are false.

“I am aware that a former disgruntled assistant of mine has made a private post implying that I had acted in an improper manner toward her,” Tambor said in a statement release on Wednesday. “I adamantly and vehemently reject and deny any and all implication and allegation that I have ever engaged in any improper behavior toward this person or any other person I have ever worked with. I am appalled and distressed by this baseless allegation.”

But will that hold any weight? And should it? You see, the tidal wave created by #MeToo shifts the burden to the accused to prove his innocence, especially among women. That’s why the takedown of Harvey Weinstein, the dethroning of former Amazon Studios chief Roy Price, and the career erasure of Kevin Spacey have been satisfying. That’s why the idea that Bill Cosby enjoyed a flourishing career years after the first of his assault accusations began bubbling up, and the fact that he’s still roaming free today, is so aggravating. What little we knew about these men didn’t leave us much reason to root for them. Actors Ed Westwick and Danny Masterson have both been accused of rape, and the details are so heinous that a person can’t help but see guilt.

A preponderance of us have experienced gender-based discrimination, harassment or assault, or are close to people who have. And a pattern has emerged among the many of the victims: their claims have been dismissed or not listened to, and their career opportunities dried up after speaking up. Some have been driven out of the industry entirely.

Or, just as horrifying, they’ve told their stories and watched helplessly as nothing is done about it and, worse, their victimizers continue to rise.

Be careful, those of you inclined to argue that this is, actually, the very definition of a witch hunt. Doing so fails to observe the heinous discriminatory asymmetry fueling actual witch hunts, where countless women were powerless to prove their innocence before a patriarchal judiciary system and died as a result.

The victims coming forward now had long felt disempowered and had nowhere to take their grievances or hope for justice. Stories upon stories tell us of network executives and production bosses and colleagues covering up for aggressors, and human resources departments either doing nothing to help or making the situation worse. Can you blame these men and women for taking their accusations to social media, the town square of 2017? Right now it’s the best chance going for a victim’s voice to be heard.

Simultaneously this also puts people like me, who are glued to our gallery seats in this courtroom of horrors, in the position of questioning our past judgment and wrestling with our current feelings. Especially critics, who championed their art and in some cases, praised their feminism. We may question our percipience and contemplate our culpability. (A popular tactic of predators is to use feminism as a cloak to gain women’s trust). Some of you guys know exactly what I’m talking about: Tell me you didn’t want to believe the allegations that have been swirling around Louis C.K. since at least 2012.

“The Good Place” creator Mike Schur didn’t — he admitted as much as he apologized for casting C.K. for a multiple-episode arc in “Parks and Recreation” in 2012. And he’s not the only one. Tell me, “Louie” fans, how many of you continued to purchase tickets to his live shows after 2015, when Gawker made more direct inquiries following up its 2012 blind item? How many of you continued to applaud him when he publicly claimed to empathize with women or spoke lovingly about striving to be a good father to his daughters?

How many of you streamed an old episode of “Louie,” purely for enjoyment, after Tig Notaro recently hinted at impropriety and expressed dismay that he has an executive producer credit on her Amazon series “One Mississippi”?

Also, if you’re like me, you may be wondering how “Better Things” co-creator Pamela Adlon, who partnered with C.K. on her FX show, is feeling right now. Few half-hour series speak to the truth, the beauty, frustrations and triumphs of being a woman with such poignancy and accuracy as that show does.

C.K. has a writing or a co-writing credit on every episode of the current season. On the top rail of the same webpage where the New York Times broke its report that included the on-record accounts of five different women he forced to watch him masturbate is a link to Adlon’s first person account, “The First Time I Ever Tried a Tampon.”

I’ve interviewed Adlon twice and found her to be a kind, warm, potty-mouthed honest human being. Now, thanks to what Louis C.K. has done I won’t be able watch her show, which airs its second season finale next Thursday, without wondering whether something happened to her too. Is she OK? What did she know about all this?

Update: Friday evening Adlon issued her own official statement via FX’s publicity department.

“Hi. I’m here. I have to say something. It’s so important.

My family and I are devastated and in shock after the admission of abhorrent behavior by my friend and partner, Louis C.K. I feel deep sorrow and empathy for the women who have come forward. I am asking for privacy at this time for myself and my family. I am processing and grieving and hope to say more as soon as I am able.”

Even if she had an inkling about his sickness, guess what? I don’t blame her for remaining silent. A common theme of the stories that have turned up as a part of #MeToo is that we’re the ones who have the most to lose by speaking up. (See: The Information’s report about “Mad Men” creator Matthew Weiner. Yep. Him too.)

On Friday C.K. released an official response to the New York Times story in which he admits his guilt. Here’s an excerpt:

“These stories are true. At the time, I said to myself that what I did was okay because I never showed a woman my dick without asking first, which is also true. But what I learned later in life, too late, is that when you have power over another person, asking them to look at your dick isn’t a question. It’s a predicament for them. The power I had over these women is that they admired me. And I wielded that power irresponsibly.”

Salon’s Deputy Culture Editor Gabriel Bell brilliantly breaks down the full text of the statement here.

When scores of women are turning over Hollywood and shaking it hard enough for tens of vile, nightmarish stories of violation to shake free and scurry into the light, nothing can be discounted. Not even when the good ones get snagged.

When I read the headline to my friend, she echoed my sentiment: “I hope it’s not true.” She met Tambor too, you see, read his book and experienced that connection. And hopefully that image we held of him is genuine and his claim of innocence is true — not only because that would mean one fewer victim in all this, but because women like me need the hope offered by the presence of good men, now above all.