Last weekend’s federal government shutdown was so short-lived that it’s not likely to be remembered by voters.

While its electoral implications are not likely to be significant, the recently-abandoned Democratic effort to utilize Senate rules to block Republicans from passing a budget “continuing resolution” will surely be remembered in the future, especially if another shutdown happens next month.

If Republicans manage to keep the Senate in the 2018 congressional elections, it’s only a matter of time before the GOP will move to further restrict the chamber’s filibuster tradition

President Donald Trump has repeatedly decried the Senate’s filibuster rules which require 60 votes to end debate on motions. They’ve been the only effective legislative tool Democrats have had since their party lacks a majority in the Senate or the House. During the shutdown, Trump renewed his past calls to abolish the practice.

Great to see how hard Republicans are fighting for our Military and Safety at the Border. The Dems just want illegal immigrants to pour into our nation unchecked. If stalemate continues, Republicans should go to 51% (Nuclear Option) and vote on real, long term budget, no C.R.’s!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 21, 2018

But Trump is far from the only Republican to call for the end of the filibuster. In September, Speaker of the House Paul Ryan affirmed his support for nixing it during an interview with Fox News commentator Sean Hannity.

“Of course I’d like to see them do majority votes on these things,” Ryan said.

Pretty much all conservative activist groups are in agreement as are numerous House members and even a few aspiring Senate candidates.

Despite the pleas of their fellow Republicans, however, the GOP’s Senate leadership continues to support the filibuster.

On Sunday, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell reaffirmed the concept.

“Now we all know in the Senate, the minority has the power to filibuster. I support that right from an institutional point of view,” McConnell said in a floor speech during which he denounced Democrats for creating a “manufactured crisis.”

As frustrating as it is for some Republicans that they cannot pass legislation without 60 votes, many of them still support the filibuster on the grounds that it might come in handy whenever Democrats end up with control of the Senate. In July, South Dakota Sen. John Thune, the No. 3 Republican in the chamber, stated that about half of his GOP members would join all of their Democratic counterparts to preserve the practice.

It is only a matter of time before a Senate majority decides to nix the filibuster, however. Its very existence is an accident and the idea that a supermajority is required to pass legislation was something that James Madison, the prime architect of the U.S. Constitution, explicitly argued against in Federalist No. 58:

In all cases where justice or the general good might require new laws to be passed, or active measures to be pursued, the fundamental principle of free government would be reversed. It would be no longer the majority that would rule: the power would be transferred to the minority. Were the defensive privilege limited to particular cases, an interested minority might take advantage of it to screen themselves from equitable sacrifices to the general weal, or, in particular emergencies, to extort unreasonable indulgences.

In the early years of American history, members of both the House and Senate could continue debate indefinitely on any issue. The lower house of Congress soon changed its rules, but the Senate stuck to the principle that “any senator should have the right to speak as long as necessary on any issue,” in the words of the chamber’s official site.

There have been several successful attempts over to restrain or restrict debate over the past hundred years. The first, known as “cloture,” is a procedure urged on the Senate by President Woodrow Wilson in 1917, which allowed debate to be ended with a two-thirds vote. Cloture was deemed necessary because a successful filibuster was able to bring all Senate activity to a halt until it was resolved. Because they were so annoying, senators rarely decided to filibuster for most of American history.

But as pressure began to build on the Southern states to grant full civil rights to black Americans, segregationist Democrats began utilizing the filibuster to block legislation they knew would pass otherwise.

Frustrated by the repeated disruptions, in 1970, Senate leaders moved to further limit the power of a filibustering member by making it possible for the chamber to move on to other legislation while a filibuster was in progress through a system called “tracking.”

While the cloture rule and the use of tracking allowed the Senate not to get bogged down on a single piece of legislation, its ultimate effect was to make filibusters more common because they were no longer perceived as such an extreme and disruptive tactic.

The abrupt increase in the number of filibusters that resulted from the new tracking system prompted another procedural change informally called the “Byrd Rule” (after the late Democratic Sen. Robert Byrd of West Virginia), which prohibits senators from prolonging debate over revenue-raising bills.

First enacted in 1974, the Byrd Rule establishes a procedure called “reconciliation,” which is aimed at helping the chamber raise an amount of revenues to match the money spent during the earlier appropriations process. Reconciliation is meant to be limited in scope, and any senator is allowed to file a challenge with the Senate parliamentarian about whether various measures are compliant. Reconciliation reduced the number of filibusters, at least for a while. They gradually became much more common in more recent decades, however, as Washington politics became more about bitter partisan conflict than back-room dealmaking.

Things changed drastically and perhaps permanently in the Senate after the 2006 midterms, when Republicans unexpectedly lost their Senate majority after roughly 10 years. McConnell was elected as minority leader to help bring the GOP back to power, while Sen. Harry Reid, D-Nev., took over as majority leader. The relationship between the two men had never been good and McConnell found himself almost immediately under pressure from his own party’s far right. He saw obstructing the Democratic agenda as the only thing that could unite Republicans. He carried this policy through into the 111th Congress which began in 2009, under newly-elected President Barack Obama.

That McConnell is hated by the extreme right is one of the strangest facts of modern-day politics since he, more than any other Republican, has prevented Democratic policy proposals from being enacted. Liberals, too, have gotten McConnell wrong in one respect: The all-out obstruction that the Kentuckian carried out under Obama actually began two years earlier, under George W. Bush.

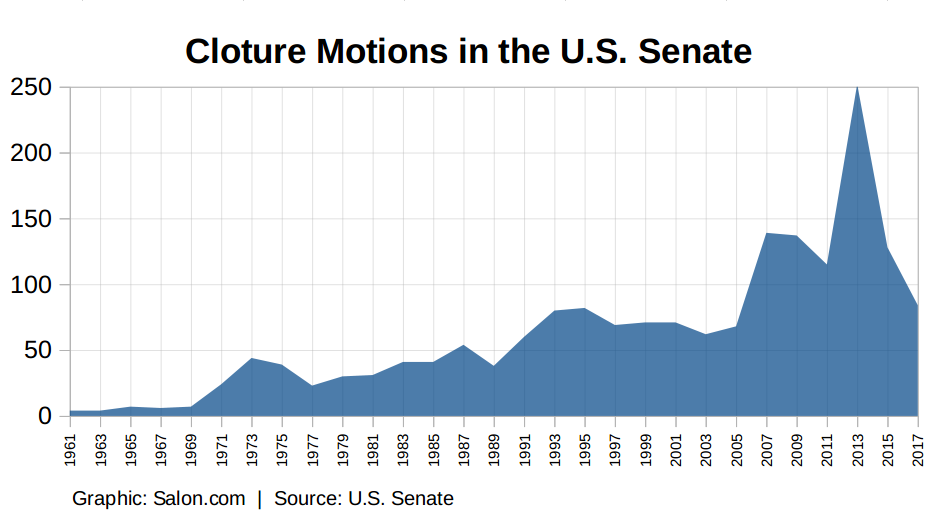

Whatever his motivations were, McConnell doubled down on the filibuster quite literally. During the 110th Congress, 139 cloture motions were filed, compared to 68 when Democrats controlled the chamber in 2005 and 2006. McConnell ramped up his legislative blocking in 2013 after Obama was re-elected and began to filibuster many of the president’s judicial nominations as well, an unprecedented move in the Senate.

Faced with such record-breaking obstruction (cloture was forced 187 times during the 113th Congress, by far the most in history), Reid and his Democratic colleagues changed Senate rules once again, making it so that federal district and appeals courts nominations could not be filibustered. This was something that McConnell’s Republican predecessor, Sen. Trent Lott of Mississippi, had described as the “nuclear option.” Ultimately, he never tried it.

Once the GOP took back the Senate in the 2014 midterms, sending Democrats back into the minority, the number of filibusters declined drastically. McConnell simply used his majority to prevent legislation favored by Obama from even being considered on the Senate floor. He did the same thing, most famously, when Obama nominated U.S. Court of Appeals judge Merrick Garland to the U.S. Supreme Court in 2016.

After Republicans took full control of both House, Senate, and the presidency in 2017, Senate Democrats, now under the leadership of New York’s Chuck Schumer, have essentially followed McConnell’s precedents. After Trump nominated Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court, Schumer and many other Democrats announced that they would filibuster his appointment. McConnell and his GOP colleagues further eroded the filibuster tradition, and changed the rules again so that Supreme Court nominations could be subject to cloture votes.

That brings us to this month, when Democratic efforts to filibuster the Republican budget continuing resolution ended up with a three-day government shutdown. While the warring parties patched together a temporary solution and passed a funding bill to keep the government running until Feb. 8, the fundamental issues — the status of some undocumented immigrants brought here as children and the budget for domestic spending programs — are nowhere near resolved.

With the Senate GOP dominated by advocates of “immigration reform” (i.e., less stringent enforcement) and the House dominated by anti-immigration hardliners, there is a strong chance that we will see another shutdown in February.

Should that happen, it will be much more difficult for McConnell to resist conservative calls to further restrict the filibuster, such as making continuing resolutions not subject to unlimited debate.

McConnell may hold the line on keeping the filibuster, this time around. But eventually someone on the Republican side will figure out that the current distribution of the American population fundamentally favors the GOP in the Senate. Every state gets two senators, no matter how large or small it is — and there are far more sparsely populated rural states than there are densely populated urban states.

Essentially, only Republicans’ increasing willingness to nominate extremist candidates like Christian nationalist Roy Moore in Alabama or Richard Rape Is God’s Plan Mourdock in Indiana has prevented the GOP from achieving a semi-permanent Senate majority.

Once that reality dawns on enough Republicans, the days of the filibuster will be numbered.

After that happens, Democrats will be forced into the the “50 state strategy” they’ve been talking about since Howard Dean was the DNC chairman but have never gotten around to doing.