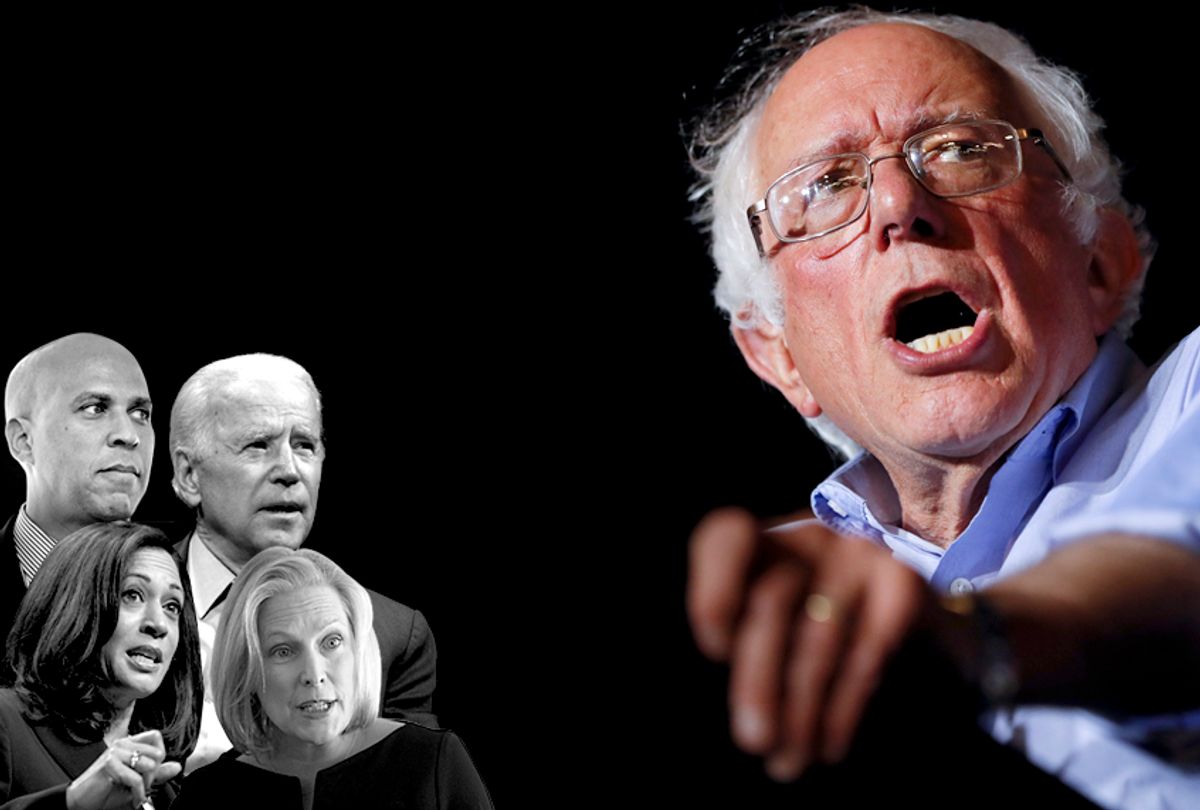

Bernie Sanders has repeatedly declined to answer questions about whether he is planning to run for president again in 2020. But last week Politico reported that Sanders had called a meeting with his top advisors to discuss a potential campaign, signaling that the 76-year-old Vermont senator is seriously considering it. If he does end up running again, Sanders would likely become the frontrunner in the Democratic primaries, and with the 2018 midterm elections quickly approaching, 2020 no longer seems that far away.

The 2020 Democratic primaries are almost certain to have a crowded field, and it is unlikely that the party establishment will get behind an avowed “democratic socialist,” even if polls suggest he is the most popular politician in America. While Sanders became a national sensation in 2016, he remains an outsider in Washington and within the Democratic Party, and his anti-establishment politics have angered more than a few party leaders. Indeed, the divisions within the Democratic Party that were evidenced during the 2016 primaries are likely to be magnified in 2018 and 2020. At the center of that debate will be the question of money in politics.

Sanders’ core message in 2016 was that the American political system has been corrupted by money, and that campaign finance reform is necessary to revitalize American democracy and pass progressive policies that are supported by the majority (yet opposed by the donor class). What made the Sanders campaign so important and unique was that it rejected support from super PACs and big donors, yet still managed to break fundraising records, proving that it was possible to run a successful national campaign almost entirely on small donations. Sanders and his team raised $218 million online, the majority of which came from individual donations of less than $200, averaging about $27 each.

This grassroots fundraising model shattered conventional wisdom, which suggested it was impossible to succeed in American politics today without the support of super PACs and big donors — a conventional wisdom Democrats have often employed to justify their long list of corporate and billionaire donors.

Of course, the fact remains that the better-funded candidate wins elections the overwhelming majority of the time, and more often than not the better-funded candidate is an establishment candidate who has the support of wealthy donors. It is also true that Republicans won’t be turning down money from their big donors on principle anytime soon. Indeed, just last week it was reported that the infamous Koch brothers will be spending up to $400 million through their political network on the 2018 midterm elections to protect the Republican majority. This, Democratic leaders will no doubt insist, is why they must continue to play the game and court the donor class if they hope to win in 2018 and 2020. As long as Republicans rake in millions of dollars from billionaire donors like the Kochs, Democrats have little choice but to do the same.

Though somewhat disingenuous, this reasoning isn’t entirely wrong. Until there is systemic and structural reform that eliminates money from politics and outlaws what amounts to legal bribery, money will remain a decisive factor. The Sanders campaign demonstrated, however, that it is possible to play the game by a different set of rules — that is, to bypass the donor class and appeal directly to ordinary citizens. More importantly, it demonstrated that popular opinion is decidedly on the side of reform — a fact that has been confirmed time and again by polls showing that the majority of Americans believe that money has too much influence in politics.

The populist explosion of 2016 was, in essence, a backlash against the establishment and the donor class, which is still ongoing. With Republicans currently in charge of the federal government, the Democratic Party has an opportunity to capitalize on today’s anti-establishment mood and lead a genuine “resistance” against not only Trump and the Republican Party, but the broken political and economic system. This would mean embracing populist candidates and adopting grassroots campaign methods, much like the 2016 Sanders campaign, which provided a template for future progressive candidates.

But the Democratic Party leadership is proving to be averse to real change. In a recent article in The Intercept, for example, reporters Ryan Grim and Lee Fang document how the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC) is currently resisting congressional candidates who embody today’s populist spirit in favor of more established candidates who have a knack for raising money:

Across the country, the DCCC, its allied groups, or leaders within the Democratic Party are working hard against some of these new candidates for Congress, publicly backing their more established opponents. In order to establish whether a person is worthy of official backing, DCCC operatives will "rolodex" a candidate. On the most basic level, it involves candidates being asked to pull out their smartphones, scroll through their contacts lists, and add up the amount of money their contacts could raise or contribute to their campaigns. If the candidates’ contacts aren’t good for at least $250,000, or in some cases much more, they fail the test, and party support goes elsewhere.

This shows that the Democratic leadership is still operating on the assumption that political success is determined primarily by a candidate’s ability to raise money and fill the party’s coffers. Of course, Hillary Clinton was a fundraising machine in 2016, bringing in $1 billion, the majority of which came from large contributions. But even a billion dollars couldn’t make Hillary Clinton -- who embodied the establishment and the status quo at a time when many Americans were fed up with politics as usual -- a winning candidate.

After 2016, one might think that the Democrats would have learned their lesson, and would recognize that all the money in the world is useless when you have no real message to sell. (As a side note, the Clinton campaign devoted less of its overall spending to policy advertisements than any candidate in the past four presidential elections, focusing instead largely on personality.) With the 2018 midterm elections fast approaching, it seems the Democratic Party has yet to truly come to terms with what happened in 2016.

The major divide between progressives and establishment Democrats in 2018 and 2020 will come down to the question of money in politics. Whether or not Bernie Sanders decides to run again in two years, his 2016 campaign proved that it is not money but the message that will win elections for Democrats in the future.

Shares