As budget discussions between Republican and Democratic leaders continue to stall, it’s starting to look like another partial shutdown is in America’s future. That may well be true even if the closely divided U.S. Senate can work out a stopgap measure to fund the federal government beyond Thursday. (At this writing, that is far from a sure thing.)

The current fractiousness in the Senate is a departure from how things worked in that chamber for much of the the mid-to-late 20th century. That has prompted many congressional observers to ask who “broke” the Senate and whether the damage can be repaired.

Spoiler alert: GOP leader Mitch McConnell had a lot to do with it. But before you can answer either question, it is useful to explain what good-government types typically mean when they refer to the Senate being “broken:” It passes fewer bills than it once did, and the two major parties have great difficulty cooperating on legislation and executive branch oversight.

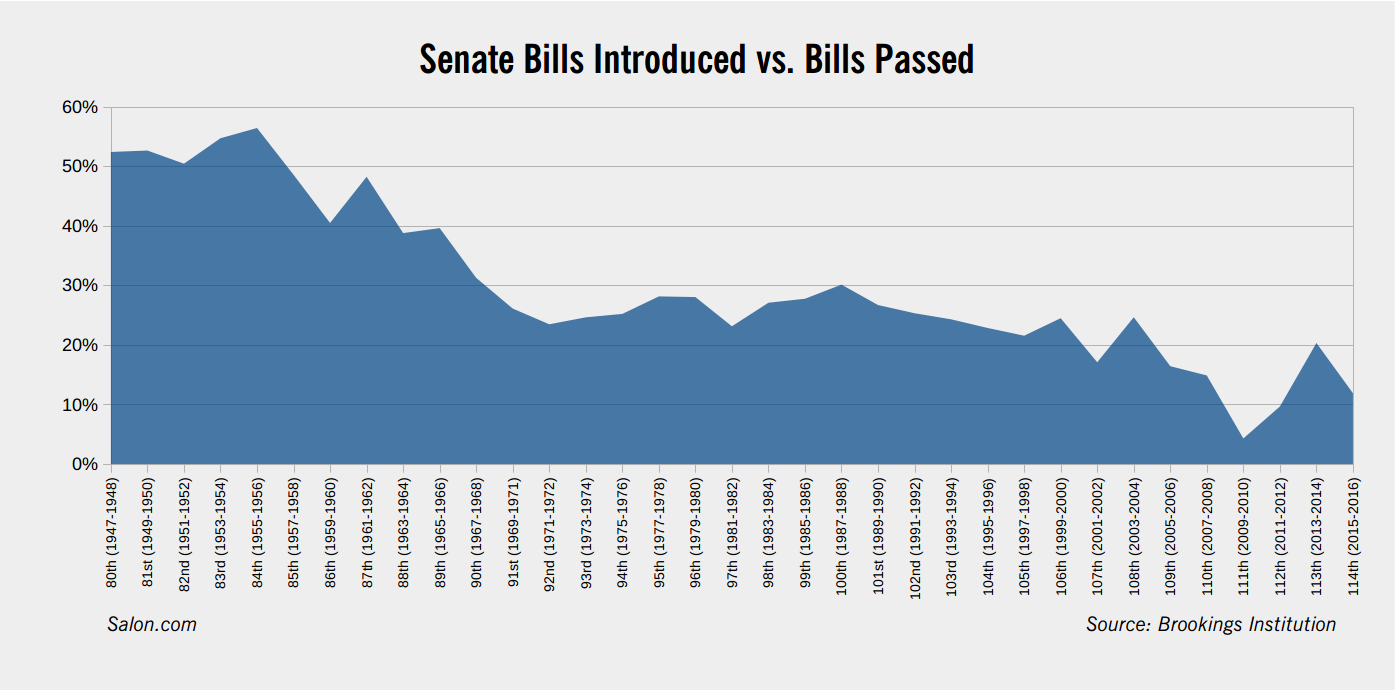

In terms of legislative achievement, it is indeed true that in recent years the Senate passes less legislation than it used to. According to data compiled by the Brookings Institution, from 1947 through 1978, the upper chamber passed at least 1,000 bills during each congressional session. Since that time, the number passed by the Senate in an average session has declined drastically. Only once during that stretch — the 100th Congress, in session 1987-88 — has the Senate passed more than 1,000.

Introducing legislation in the Senate seems to have become largely a matter of political posturing, rather than a good-faith attempt to enact law. During the 114th Congress that wrapped up in 2016, just 12 percent of all bills that were introduced actually ended up passing. That’s a dramatic departure from during the 1950s when upwards of 50 percent of bills went through.

Political scientist Molly Reynolds, author of an extensive book on the history of the Senate filibuster, explained one of the biggest reasons for the Senate’s decline in productivity during a panel discussion hosted by Brookings on Monday. After a period of long-term political stability, control of the Senate has become much more vigorously contested between the Republican and Democratic parties since the 1980s.

Since Ronald Reagan’s first inauguration in 1981, Senate control has changed hands between the parties seven times, with five of those switches coming since 2001.

Why has Senate become so much more partisan? The biggest factor was the emergence of the American conservative movement that rose to prominence alongside Reagan. Ironically enough, that development fulfilled the wishes of Progressive-era activists such as President Woodrow Wilson, who called for America to move toward a more ideologically coherent political party system where members would vote en masse instead of individually.

Wilson and other “liberals” of that era — the word admittedly doesn’t quite fit — also argued that our nation’s constitutional system was fatally flawed, because the separation of powers guaranteed an inefficient central government. (Today Donald Trump would likely agree.)

“No living thing can have its organs offset against each other, as checks, and live,” Wilson argued in a 1912 campaign speech.

Wilson presumably never would have imagined that it would be the anti-government conservatives who took control of the Republican Party in the 1960s and ’70s who would move the United States toward the disciplined partisan system he advocated.

Before the right succeeded in capturing the GOP, the major parties were ideologically heterogeneous: There were liberal Republicans in the Northeast and conservative Democrats in the South, along with moderates in both parties whose differences were largely cosmetic. Nowadays, the parties have shifted toward the left and right.

As both parties have moved toward more ideological homogeneity, they have also moved toward much greater legislative bloc-voting. The rise of McConnell, who has enforced iron discipline among Republican senators (with a few notable exceptions), has certainly contributed to this fact. The Senate’s all-time low in the graph above was achieved in the 111th Congress when McConnell squared off against Democratic president Barack Obama.

“Their goal is to slow down activity to stop legislation from passing in the belief that this will embolden conservatives in the next election and will deny the president a record of accomplishment,” Sen. Dick Durbin of Illinois, the Democratic whip, said at the time.

But even as party discipline has increased drastically within both the House and Senate, the upper chamber’s rules, especially the unlimited debate allowed by the filibuster, have stood in the way. So as both sides have become more disputatious and allergic to bipartisan compromise, the Senate has also become less able to function.

“The Senate has perhaps been the major casualty of the movement away from deliberation and toward party unity,” observed William Galston, a colleague of Reynolds at the Brookings Institution.

“It’s yet another case of ‘beware of what you wish for,’” he added.

While senators of both parties frequently complain about how the “world’s greatest deliberative body” conducts business in a viscous and vicious manner, resolving the situation will not be easy.

Some observers, including Ira Shapiro, a former senior congressional staffer who has worked for lawmakers in both parties, are calling on senators to bind together to check the power of the imperial executive, as they did in the days of Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter and Reagan.

While that idea gets a lot of lip service from the pundit class, it’s highly improbable in an era when Republicans like Sen. Jeff Flake — or Democrats like former Sen. Joe Lieberman, for that matter — are run out of town for defying their parties’ base voters.

What we’re likely to see instead, as I wrote last month, is the further erosion of the Senate filibuster. That’s especially probable once it becomes more obvious to Republicans that they have a built-in advantage in the Senate, thanks to the geographic concentration of liberal voters in a few large coastal states and the fact that nowadays few people vote for different parties in presidential and congressional elections. (Such “split-ticket voting” used to be more the rule than the exception in many heartland states.)

Eliminating or restricting the Senate filibuster will likely lead, in the short term, to Republican majorities pushing through laws that most liberals and progressives won’t like.

Ultimately, however, that outcome may be necessary to “fix” the problem of the Senate’s inability to pass major legislation. That’s because if more far-right legislation makes it through the Senate, the long-term consequences will likely include the diminution or defeat of the anti-government right.

That may sound counterintuitive, but it’s not. Republicans will finally have to be accountable for the policies they advocate, something they have largely avoided thanks to their deployment of cultural populism, meaning the long-standing practice of using hot-button cultural issues to distract the public from the conservatives’ wildly unpopular economic policies. In the end, the GOP will pay the price for building congressional majorities on lies and deception, and those majorities will almost certainly collapse under their own weight. Either they will pass politically suicidal legislation and get massacred for it or they will have to implicitly admit that the Republican plan during the Obama years was to deliberately fail to legislate in the hopes of riling up their base.

America got a preview of what might happen if the filibuster were abolished, during the presidency of George W. Bush when the GOP briefly had full control of the presidency and both houses of Congress. Despite Bush’s campaign promises to slash the budget, Republicans in Congress did no such thing: They actually increased federal spending and even created a new Cabinet-level federal agency, the Department of Homeland Security. Under Bush, Republicans increased government spending more than any of the six presidents who preceded him.

We saw the same thing happen again during Republicans’ successive failures to roll back the Affordable Care Act. Instead of fulfilling their promises to gut Obamacare, Republican senators from swing states refused to go along with the party’s plans to boot tens of millions of people off federally subsidized health insurance plans.

Making Republicans answer for their many years of cheap anti-government rhetoric is likely to be the only way to force the American conservative movement to grow up. That seems to have happened to a large degree in Louisiana and Kansas, where GOP legislators in both states openly flouted the far-right by raising taxes in the face of titanic budget deficits brought on by previous cuts. A similar thing has essentially happened outside the United States: No center-right party in any major industrialized country actually advocates against national health care or a comprehensive welfare state.

On the other hand, there’s no telling how long it might take for the GOP’s asymptotic nihilism to work itself out, or what terrible things might happen while it does. Who knows what President Trump and a Republican majority, unrestrained by the Senate filibuster, would actually do?

Woodrow Wilson’s prescription for open political combat may be filled at last. But America may have to go through some incredibly tough times to find out whether it’s the right medicine.

Democrats could even help with the process, should they gain control of the Senate in 2018, by ditching the filibuster themselves. As a bonus, it would make them even more effective in blocking Trump.