Cutter Wood wasn't a true crime obsessive. He wasn't the sort of man who could rattle off his favorite unsolved murders and disappearances. He was a graduate student studying in Iowa, whose mother just happened to send him a newspaper clipping about a suspicious motel fire on Anna Maria Island, In Florida.

The blaze — and concurrent investigation of its missing owner, Sabine Musil-Buelher, — intrigued Wood, who had been a guest there a few months before. And that small connection drew Wood into a mystery that would encompass nearly ten years of his life, involve three compelling suspects and form the basis for his haunting debut, "Love and Death In the Sunshine State."

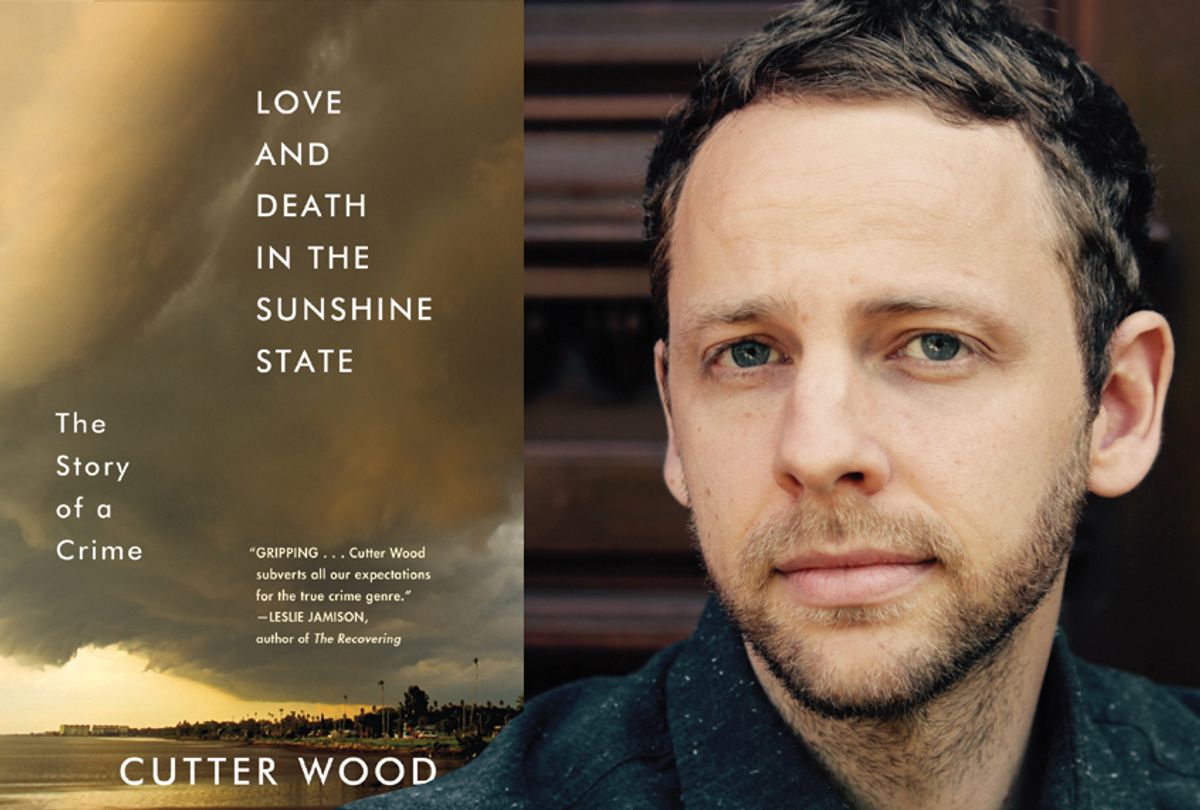

Salon spoke recently with Wood about the small town crime that fascinated him, about writing what it feels like to die and in finding the humanity even in a person who commits the darkest deed.

Your mother sent you this newspaper report and you almost immediately got sucked in. Why did this crime resonate with you at that moment in your life that it did?

In some ways I could never truly understand why I went down [to Florida]. I received that article. It just seemed strange that two weeks after this murder — it was most likely a murder — someone would then still feel so roiled inside that they would feel obligated to go and set fire to the motel. That really, really came into it.

Then there were all these tips and leads coming into the sheriff's office after the woman went missing. They were just so peculiar. It's this little island, and people were really having these hallucinations. They saw her everywhere. They saw her at the Goodwill and the Salvation Army, they saw her at a bar with a man dressed like a pimp. They saw her looking disheveled and upset. They saw her at the orthodontist's office. They saw her at the Sarasota International Airport boarding a plane. One woman I spoke with was totally confident that Sabine was going to communicate from the afterlife with her through the shape of her pet parrot. Part of my original interest was really just trying to figure out what was going on in this community,that they were filling this place where this woman had been with all of these kind of strange hopes and desires and reactions.

But you were also going through your own things in your life that that drew you to this. You could have written a book that was just straightforward reportage, but you didn't.

I was interviewing a number of people, in particular interviewing Sabine’s boyfriend, William Cumber, about their relationship. At the same time, I had just moved in with the woman who was then my girlfriend, now my wife. A lot of the same issues that they were having were ones that I thought were reflected in my own life. First of all, just talking with William Cumber made me reflect on these things. Then secondly, I felt like if I was going to subject him to this scrutiny, I had to turn the camera back on myself and subject myself to the same scrutiny. Then you became part of the story because it is such a small community, and you developed this relationship with one of the prime suspects. It's still strange to me to say that I have a relationship with William Cumber, who was one of the suspects. I've got a big box full of letters here, and there's bound to be something that develops between you. It’s not something I'm totally comfortable with.

What was it like in your experience living this in real time? You maybe believed certain things about the way that events transpired, and then in the course of events found out, no, actually, things that I heard, things that I believed were entirely different.

The strangest thing about this entire project was that the day I sent what I thought was the final manuscript to my agent. I sent it maybe at 10:00 in the morning, and at 10:15 I hopped on the computer and there'd been a confession.

At that point in time, I had become close enough to people down there. I was so emotionally shocked when the confession occurred just because there had been this threat of a trial for a long time, but it seemed like it was never going to happen. There was no body. There was still no murder weapon. There was still really no defined motive. It really seemed like a long shot that there ever be any kind of resolution. I'd kind of written an entire book with that presumption and I was okay with that. I thought that that open-endedness was not a terrible thing. Then to send it out and 15 minutes later find out that everything has been clapped shut. I was really, really struggling.

I would imagine both professionally and personally.

I definitely spent years writing something and putting together the sequence of events, and even if they're somewhat or largely confirmed, it was still weird to see it all suddenly play out so quickly.

I want to ask you about something you did which was very, very bold. You go into the experience of the murder from the point of view of the victim and also from the point of view of the murderer. That's a very unusual device. You get into that experience of what it would feel like to be murdered. I wonder how you did that. There must have been intense.

It certainly is a part of the book that I almost always planned to take away eventually. You write all these different things and see what happens. You don't really have a concrete idea. It was something that I realized was a big decision and I wasn't at first sure if I was prepared to make that decision.

I had all of this data on what would have happened, photographs of her apartment and all these very general things. I also had done lots of research about — it's painful to talk about — what are the experiences of dying? What is the physical bodily experience? I wrote a lot of that before the confession happened, before we knew exactly what had happened. In fact, I wrote just tons of different versions. At that point in time I had no idea of exactly how the murder had occurred. It was just too gruesome that I kept dialing it back and dialing it back to the point that I thought it felt palpable to me. Then of course, when the confession occurred, it turned out that the most recent version was in fact the real one. I thought it was important to keep those perspectives in there because for me, a lot of the book is about not giving preference to a single perspective. That's kind of the elemental difficulty of a relationship. I felt like I needed to do that there.

And then to get into the baffling experience of committing the murder as well, the surprising aspects of what it would feel like to kill somebody.

I went down and was able to just sit down with the man who confessed the murder and we spent probably close to a week talking. It gave me the full breakdown of everything from the moment he first met Sabine to what it was like to to roll her body up in a sheet and bury her. It was one of the strangest and definitely most difficult things in my life doing that. I can't think of really many times when you are required by this thing you've gotten into to go through that experience, to sit down and have someone tell you what it's like to murder.

I would imagine that really, really gets in your head.

I can't say that I understood what he was going through or even exactly why he did it. But I knew there was more to him than simply that he was a murderer.

It is easy to kind of turn a real experience of violence into entertainment. To forget that the victim had a life, was a fully realized person, and that the murderer was as well. The person who commits a crime is also someone who was somebody’s child, who maybe had hopes and dreams, and who then committed terrible acts.

I feel like it's dangerous, as a person, that it’s dangerous to society, to ignore that murderers are also often people, and these things don't just come out of nowhere. That was definitely a big thing that was on my conscience and my consciousness while I was working on this. I wanted to make sure that this is a story about human beings.

Without in any way blaming the victim or making excuses for the murderer, but seeing it as a complicated story that has humanity in it. What's it like now in the aftermath of that? Where are you now within this story that has had a resolution?

I got into this thing when I was 24 and didn't expect it to be very a life-consuming thing. I thought the first time I'd just write a short essay about the way these people on this island had been affected by this. It turned into this multi-year project and involved going down to Florida all the time and driving up to prisons and jails, interviewing people and going to detectives. That’s just my way of saying I had no idea what I was getting into and I'm still not sure what the full ramifications of it are. I would love to never write anything this dark again. It took a toll on me very much emotionally, just terrible dreams and the stress of wanting to make sure you weren't doing something that would really hurt somebody's feelings or damage their lives in any unnecessary way. I'd like to move on to something a little bit lighter.

Did this book turn you into a true crime person now?

It's funny though because I get the allure. All through this process I've been trying to understand what that allure is and why I feel it. I guess as a kid, I remember going to the library and finding Sherlock Holmes on the shelf and not even making it to the checkout counter. I just stood there and read the book cover to cover, because I was so engrossed. It’s not even like that's fantastic literature, but there is something captivating about it. It's not as though it doesn't exist somewhere in me, but definitely I feel like the thing that motivated me was just wanting to describe the life of a relationship, what it's like for two people to fall apart or stay together.

It's really haunting because it is a human story. It's not just a story about a crime. It's a story about a community and about a woman and about a killer and this confluence of events in which you do feel the almost cruel randomness of it.

It's just made it hard for me to read the paper. Especially just because that part of Florida, when I talk to reporters down there, it's like, “This is not that crazy of a crime. There are people getting chopped up and stuffed in sewer drains all the time.”

Sure, because Florida.

It's a disconcerting way to look at society.

That there is a certain degree of humanity or pathos in true crime that really fascinates me. Yours is a story about a person who becomes enmeshed in all sides of it — from the victim to the perpetrator — and what happens when you find yourself at that crossroads. It makes you confront uncomfortable feelings about the perpetrators.

People do things, and I include myself in this, that they don't understand. Maybe for reasons that are very dim and historical. That to me is a fascinating question — why do we the incomprehensible things we do?

Shares