Congressional primaries in California are less than a month away, with at least seven Republican-held seats seriously in play this November (according to Cook Political Report, and targeted by Swing Left), the most of any state. Four of those seats are in or adjacent to Orange County, once the home of Richard Nixon and the epicenter of conservative power, where Democrats now hold a numerical advantage.

But there's a perverse twist. Thanks to California's nonpartisan "jungle primary" -- in which the top two candidates advance to the general election, regardless of party affiliation -- Democrats could conceivably be shut out in as many as three of those races. Two Republican incumbents are retiring -- Rep. Darrell Issa and Rep. Ed Royce -- while a third, Rep. Dana Rohrabacher, faces a serious GOP challenger. With an overcrowded field of Democrats, it's possible that Republicans could finish first and second in those primaries. For those reasons and others, these Orange County races provide a miniature study in the struggles inside the Democratic Party today.

On one hand, there's a hyper-energized progressive base producing significant changes among presidential hopefuls and other national figures. Jeff Spross argued recently that “Bernie Sanders has conquered the Democratic Party,” at least as far as key policy proposals are concerned, given the broad support for Medicare for All, a $15 minimum wage and debt-free college education, and growing support for various versions of a national job guarantee from such diverse figures as Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand of New York, Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey and, less surprisingly, Sanders. It's somewhat reminiscent of the way the 2008 campaign advanced the single issue of health care reform.

On the other hand, the party's core political functionaries remain wedded to a backward-looking and demonstrably failed model. Despite polling that suggests strong swing-district support for a progressive economic agenda, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee is trying to win with a bevy of “me too” GOP-lite candidates. That may well work in the short run, as it did most dramatically in the wave elections of 2006 and 2008, but could set the party up for further failure in office and deeper disillusion down the road. (See my look back at the elections of 1994 and 2010.)

One especially trenchant observer on this front is activist, blogger and longtime music exec Howie Klein, who has repeatedly expressed his frustration with the Democratic Party's efforts to intervene in the midterms, and the way the struggle has been covered in the media. Klein discussed the Southern California races recently on his Down With Tyranny! blog, writing that DCCC-favored candidates "are always conservatives and never independent-minded agents of change.” A day before that: “The DCCC has 38 candidates on their Red To Blue list so far. I count three who are worth voting for — and I'm not even 100% sure about one of the three. At least nine of them are outright Blue Dogs. … And 21 of them are admitted New Dems.”

In that same post, Klein predicted that Democrats would fail to break a familiar cycle, and were setting themselves up for yet another GOP comeback down ther road:

There was a 9.1% swing towards the Republicans in 2010 but that was primarily because the Democratic base was disappointed and disillusioned with the Blue Dogs and New Dems 2006 had delivered them.

That's exactly what's going to happen in 2022. Exactly. [Rep. Ben Ray Luján of New Mexico, head of the DCCC] and his imbecile crew are making sure of that by crushing progressives in primaries in favor of Blue Dog and New Dems.

Klein has been following such machinations in races across the country, sometimes individually, sometimes in pairs or larger groups, and he explores a variety of different ways to slice things up. Focusing specifically on Orange County and districts that overlap it, an April 18 post looks at the Democratic focus on wealthy self-funded candidates, with a few other examples by way of comparison.

In California's 39th district, where Republican Rep. Ed Royce is retiring, the DCCC actually wound up recruiting two wealthy candidates able to fund their own campaigns, lottery winner and former Republican Gil Cisneros and Vietnamese-American physician Mai Khanh Tran. Neither of them had previously lived in the district or had strong community ties there, which epitomizes the Democratic Party's problem.

As of the FEC reporting deadline on March 31, Cisneros had given his own campaign $2.5 million, about 82 percent of his total fundraising, while Tran had given her campaign $480,000, about 41 percent. Yet another candidate, health insurance executive Andy Thorburn, had funded his own run to the tune of $2.3 million, more than 91 percent of the total.

In an earlier post, Klein looked at how much money came from individual small donors in the 39th district, and the results were particularly striking, For Thorburn, it was much less than 1 percent, and for Cisneros about 1.8 percent. Tran had raised about 12.5 percent of her funds that way, while a fourth Democrat, Sam Jammal, looked like Bernie Sanders by comparison, raising 27.3 percent of his money from small donors. The fact that he's an outlier speaks volumes about the candidate problem within the blue wave.

None of this is exceptional. In California's 48th district, where longtime GOP Rep. Dana Rohrabacher is clearly vulnerable, two leading Democrats, Harley Rouda and Omar Siddiqui, have funded well over half their own campaigns, with sums in excess of $700,000 apiece. In the 49th district, where Issa is retiring, the problem is even more acute. One Democrat, Paul Kerr, has given himself more than $1.6 million, 83 percent of his campaign total; another, Sara Jacobs, has self-funded with just over $1 million, 77 percent of the total.

In contrast to this lineup, Klein argues (and I would generally agree) that in three of these four districts there are strong candidates “who have a shot at winning and who aren't trying to buy the seats ... and who are actually trying to win based on their ideas, values and intentions towards the working families of the districts.” (Those would be the aforementioned Sam Jammal in the 39th, Katie Porter in the 45th and Doug Applegate, who nearly unseated Issa in 2016, in the 49th.)

More could be said, of course, about the specific details of these races. But my emphasis here is on how candidates in this particularly rich area for seat-flipping reflect problems that are endemic throughout the Democratic Party. Since the DCCC has only endorsed one candidate in California so far, it's not entirely fair for Klein to blame the problem of self-funding (and carpetbagging) on decisions made at party HQ in Washington. It's clearly much broader than that.

Remember that polling data I mentioned? It came from Celinda Lake, polling for the Congressional Progressive Caucus PAC, Democracy for America, the Progressive Change Campaign Committee and the Roosevelt Forward. According to Lake's memo, the poll of voters in 30 swing districts finds that progressive Democrats have a tremendous opportunity "to run and win on progressive policies." She continues: "We found that in these districts, mostly held by Republican incumbents, voters enthusiastically support progressive policies and progressive messaging works, both to persuade swing voters and to mobilize the base."

The most intensely popular policies focus on prescription drugs, health care, infrastructure, protecting Social Security and Medicare, and cracking down on Wall Street, and these policies were popular with both swing voters and surge voters [i.e., hardcore anti-Trump Democrats]. Prescription drugs are so popular that they are seen as a core value across all demographics, with even 66% of Republicans strongly in support of allowing Medicare to negotiate prices like the VA.

Initially, Lake found Democrats lead Republicans on a generic ballot by 11 points (46 to 35 percent) with a similar enthusiasm gap among strong supporters (38 to 27 percent). After exposure to those progressive policy proposals, the Democratic lead rose to 18 points (49 to 31 percent). Lake's report concludes: “This shift includes expanding the margin with white non-college voters from +5 points to +9 points from the initial (43% Democrat, 38% Republican) to the final (45% Democrat, 36% Republican) ballot.”

This underscores how out of touch with reality the Democratic Party establishment is, since it still believes (or claims to) that progressive policies are electoral poison. Things look markedly different from the grassroots looking up, where more and more attention is focused on breakthrough figures who can help shift the “common sense” assumptions that so often mislead us. Further up the ballot, there's a clear choice that has progressives in California excited: State Senate President Kevin de León's primary challenge against longtime incumbent Sen. Dianne Feinstein.

Feinstein has "lost the confidence of the California Democratic Party," in the words of Bill Honigman, state coordinator for the Progressive Democrats of America. She was unable to gain the party's endorsement at its recent state convention, “because she has all too often voted along the lines of the conservatives in the Senate, even the Republican majority,” he said.

“Most of us who consider ourselves to be progressives know that we need big bold action on critical issues: Health care, education, the environment, mass incarceration,” Honigman said. “All those things need big, bold steps, not baby steps, and Feinstein represents the incrementalist baby-step approach."

R.L. Miller, who chairs the state party's environmental caucus and founded the Climate Hawks Vote PAC, said she believes de León “is putting together a remarkable coalition — labor, environment, Latinos, well educated whites, millennials and youth voters — that reminds me a lot of the Obama coalition circa 2007-2008."

She continued, “Usually, when I see that a candidate is endorsed by some of the fossil-fuel-friendly unions, I worry about their climate policies. Not Kevin -- he's doing something truly remarkable." Along with most other observers, Miller expects de León to finish second to Feinstein in the primary election -- but remember, that means they will face each other again in the fall. "The more people learn about him the less they'll vote for Dianne Feinstein,” Miller concluded.

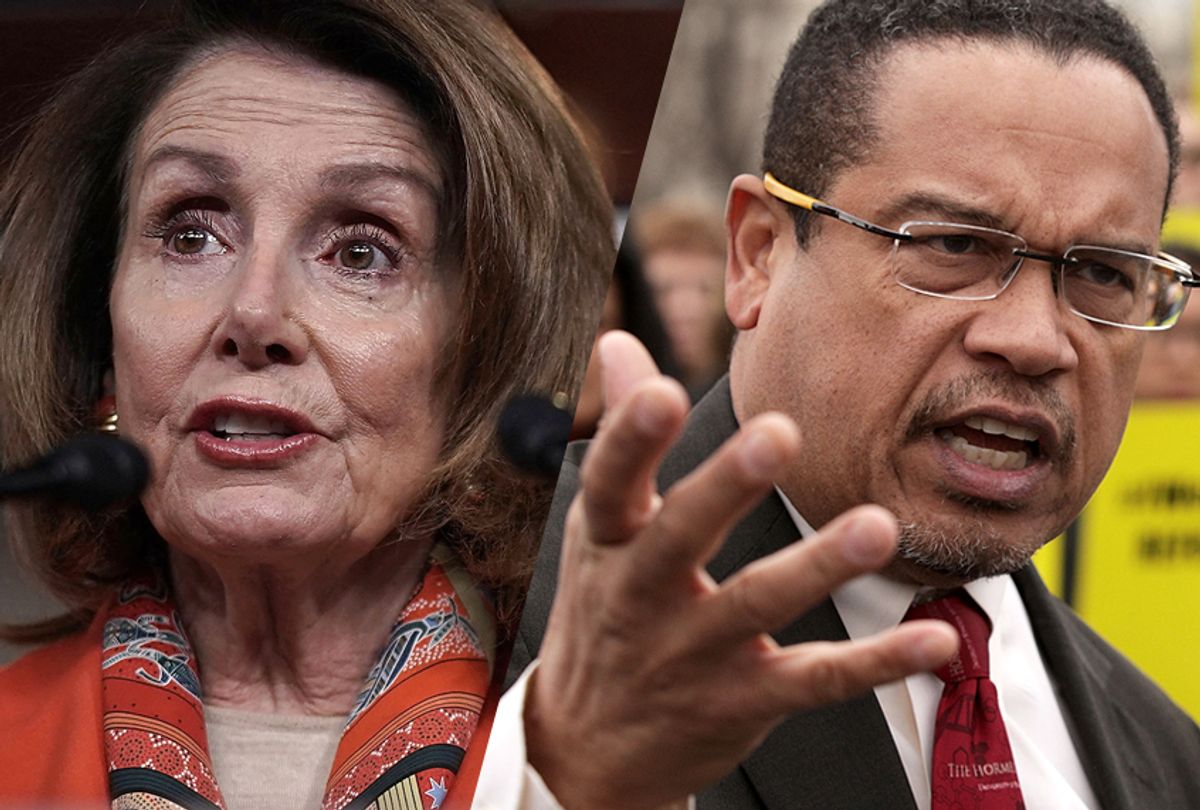

Two other facets of intra-Democratic struggle deserve notice here. The first is the question of who should be House speaker next January if Democrats win a majority, as most people on all sides of politics now expect. While there's plenty of progressive grumbling about Nancy Pelosi, it seems to be the “centrist” or conservative Democrats who are leading moves within the caucus to dump her, which is not likely to play well with an energized base after a big win in November.

The second is the issue of how or whether Democrats should limit the role of superdelegates in the presidential primaries for the 2020 election. This was highlighted at Truthdig recently by Norman Solomon, co-author of last year's progressive report, “Autopsy: The Democratic Party in Crisis,” which I wrote about for Salon here.

“The issue of superdelegates is a matter of democracy,” Solomon explained by email. “There's no real way to justify superdelegates unless one accepts the idea that current party officials should have an extra say about who becomes the presidential nominee.” He pointed out an obvious contradiction: “Many of those officials are apt to feel disenfranchised if their superdelegate status disappears — but the reality is that the existence of superdelegates actually disenfranchises the voters. Their choices are supposed to be the essence of democracy.”

Defenders of the superdelegate system often argue that it did not provide a decisive margin of victory in the 2016 race between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, or in previous campaigns. Solomon calls that claim misleading, and said it "avoids basic realities of what the superdelegate system ends up doing":

The distorting and undemocratic impacts of superdelegates have gone way beyond their numbers. By November 2015, Hillary Clinton had already gained public commitments of support from 50 percent of all the superdelegates — fully 11 weeks before any voter had cast a ballot in a state caucus or primary election. Such a front-loaded delegate count, made possible by high-ranking party officials who are superdelegates, can give enormous early momentum to an establishment candidate.

Superdelegates were always intended to give more power to elected party leaders, justified in large part by their proven ability to win elections. But that ability lies in shambles today, as never before. Any victory that Democrats win in the coming midterms is clearly going to be driven from the grassroots. If the party hopes to win in 2020, the same should hold true then as well.

One example of how this plays out is found in Swing Left, a new organization focused specifically on flipping the House by supporting activists in swing districts and connecting them with supporters around the country. The effort has proved remarkably successful so far, according to Jennifer Stokely Eis, who oversees the western U.S. Swing Left does not endorse candidates in any primary, but the group does just about everything else — it helps register, identify and turn out voters, and is committed to raise funds for eventual district nominees.

"We demonstrated what that model looks like in a couple of recent special elections," said Eis, including Rep. Conor Lamb's surprise victory in Pennsylvania's Trump-friendly 18th district and the election in Arizona's deep red 8th district, where Democrats narrowed the margin to five points. This candidate-neutral role keeps Swing Left out of intra-party struggles, but recruiting and training hundreds of thousands of activists can't help but empower grassroots campaigns for a more responsive party. This is bound to have repercussions in the years ahead.

One way to make sense of what's going on more broadly in our politics was recently laid out by Nancy Fraser, a professor of philosophy and politics at the New School, in a recent issue of American Affairs, "From Progressive Neoliberalism to Trump and Beyond."

To explain where we are and how we got here, Fraser employs Antonio Gramsci's concept of "hegemony," meaning “the process by which a ruling class naturalizes its domination by installing the presuppositions of its own worldview as the common sense of society as a whole.” The key to that process is “the 'hegemonic bloc': a coalition of disparate social forces that the ruling class assembles and through which it asserts its leadership.”

Although the economic and social ideology we now call "neoliberalism" came from the right, she explains, “the right-wing 'fundamentalist' version of neoliberalism could not become hegemonic in a country whose common sense was still shaped by New Deal thinking, the 'rights revolution,' and a slew of social movements descended from the New Left. For the neoliberal project to triumph, it had to be repackaged, given a broader appeal, linked to other, noneconomic aspirations for emancipation.”

In short, that's how we wound up with "progressive neoliberalism," which “combined an expropriative, plutocratic economic program with a liberal-meritocratic politics of recognition.” That's what Bill Clinton and the “New Democrats” put in place in the 1990s, and at least arguably what Barack Obama continued for the most part, even after the financial crash and the Great Recession exposed its flawed foundations. In the 2016 election, progressive neoliberalism was confronted by populism on two fronts -- from the Bernie Sanders left and the Donald Trump right -- and paid the price.

Establishment Democrats generally seem to believe they can put the "progressive neoliberal" coalition back together again, perhaps with some additions and adjustments. They may be correct in the short term, but it's anyone's guess where the party's internal combat will lead over the next few years. At the very least, we can say this: The more open, healthy and democratic the process is, the less likely it is that liberals and progressives will repeat the mistakes that led to their current predicament.

Shares