The framers of the U.S. Constitution understood that a free press was essential for a healthy democracy. It is a check on power, a "watchdog and witness" that provides citizens with the necessary facts and information to make political decisions. This is why authoritarians and demagogues such as Donald Trump consider a free press to be their mortal enemy.

Following an old script, Donald Trump has at times encouraged violence against reporters and journalists and clearly holds the First Amendment in contempt. He has threatened to shut down newspapers like The Washington Post that dare to criticize him by exposing his likely criminal behavior and naked corruption. He has personally mocked and derided journalists who he does not like.

Like other authoritarians and fascists, Trump is waging a war on truth and reality. His primary weapon is constant lying, along with undermining the credibility among the American people (and especially his followers) with slurs about "fake news." This is essentially a contemporary version of the Nazis' "Lügenpresse" campaign.

And like other authoritarians, Trump has his own version of state-sponsored media in the form of Fox News and other areas of the right-wing echo chamber, to circulate lies and other forms of propaganda in support of his regime.

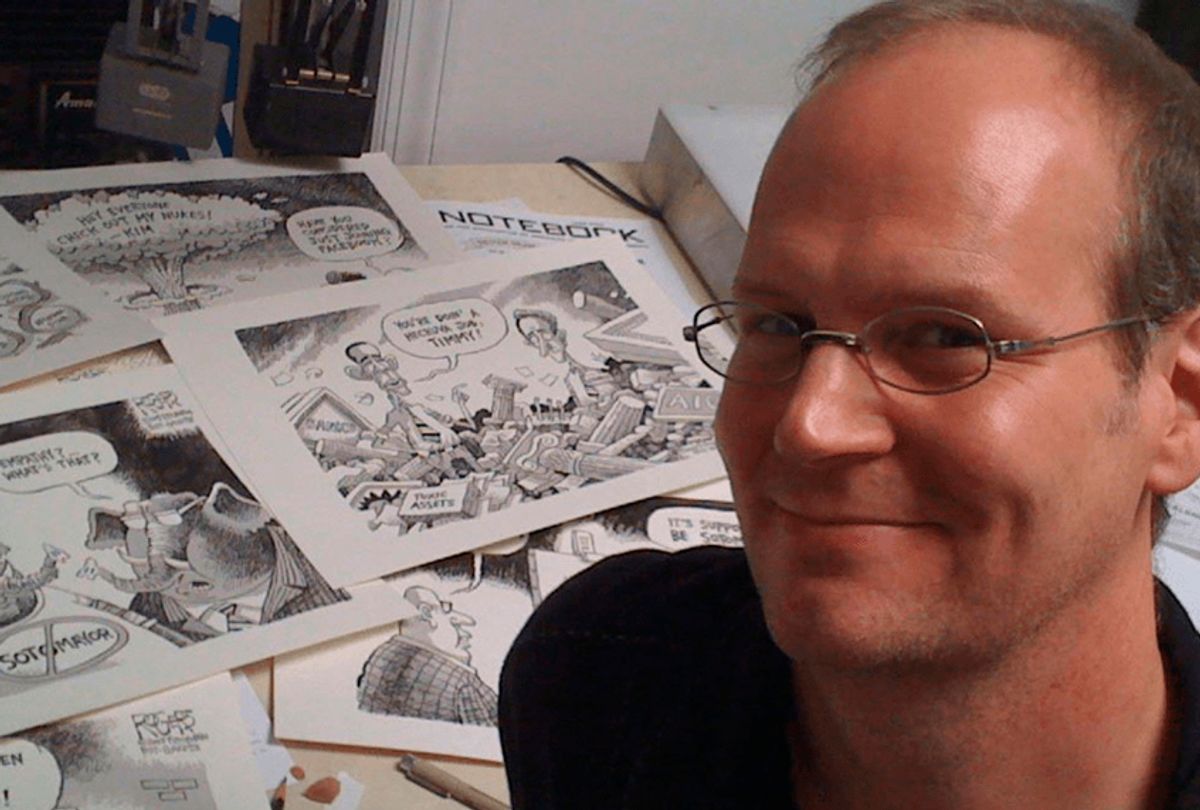

Trump's assault on the free press has found allies among publishers and editors who support his assault on democracy. Several weeks ago, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette fired editorial cartoonist Rob Rogers, ending his 25-year tenure at the newspaper. He is a Pittsburgh institution and one of America's most popular and widely-read political cartoonists. Why was he fired? Rogers refused to stop drawing cartoons criticizing Donald Trump.

I recently spoke with Rogers about his recent experiences. We discussed the obligations of a political cartoonist in the age of Trump, why Rogers decided not to surrender to a virtual gag order on caricatures of Trump and the challenges of drawing political cartoons about a real-life politician as grotesque as this one.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length. A longer version can be heard on my podcast or through the link embedded below.

<iframe sandbox="allow-same-origin allow-scripts allow-top-navigation allow-popups" scrolling=no width="100%" height="185" frameborder="0" src="https://embed.radiopublic.com/e?if=the-chauncey-devega-show-6N90ql&ge=s1!49cc84c6804156ef9543ec5b1380f97ae97f2ddd"></iframe>

How are you doing? Given this moment, being fired for criticizing Donald Trump seems almost predictable but no less troubling.

It is predictable in some ways because of what's happening in Washington and around the country. But it is not so predictable for a large major newspaper in a city that’s fairly sophisticated. You could see this happening maybe at a small paper that's owned by a more conservative publishing conglomerate -- for example, the Sinclair news organization. Pittsburgh has been a traditionally liberal city, where there's a running joke that if you want to vote for mayor or any of the other city offices, you need to be a registered Democrat because the real voting happens in the primary.

As far as how I'm doing, I'm still a bit shocked. I'm still reeling from all the public support and the media attention that's been heaped on me. I'm very grateful for all the support, and I'm really touched by the notes of condolence from readers saying, “They never should have done this, and you're a great cartoonist.” So that's really uplifting. I work alone in my studio, and I see the reaction sometimes if my wife looks at a cartoon. But I rarely get to see people reading it. So this has really proven to me that the cartoons have reached a lot of people, and I'm very humbled by that.

Tell me a little bit about how this all unfolded.

It was a slow build. Three months ago when the new editor took over, I had a real sense that this day was coming. I knew we were not seeing eye to eye. I also knew that if I continued to do my job in the way it needed to be done that I was going to be butting heads with management. But it was a little bit of a shock that they didn't try harder to keep me. Even after the six cartoons that were killed in a row and the public outcry in response, and they were getting media calls and other attention. Even after that, they came to me with a terrible contract and said, “Here, sign this.” I was like, “You've got to be kidding!”

What were the details of the contract?

The guidelines were much more onerous and draconian than even what I was working under with the new editor. They wanted me to be reined in even more, and I was already having trouble. So, I said, “No, I can't sign this in good faith.” Then I waited. I basically responded with, “How about that we just go back to what I originally proposed. Put me on the op-ed page, I'll continue to do the work that everybody loves in the paper, and you guys can have your editorial page all to yourself and not worry about me messing it up.”

I had proposed that three months ago with my new editor. At the time he said, “Well, that's an interesting idea.” But then he never really followed up on it. Then I suggested it again when this all started, and then once more. But instead of getting right back to me they waited a week-and-a-half, and then when I went in to see them again, it was simply to be told, “You're no longer an employee.” So they dragged it out quite a bit, just to make me sweat.

Trump is the result of many decades of institutional failure in this country. This moment is a crisis of personal, societal and moral truth. The job of a political cartoonist is to tell the truth as he or she sees it, right? Those truths are often uncomfortable.

In my opinion, the editorial cartoon is supposed to be provocative. It is supposed to make somebody uncomfortable when they look at it. Now, hopefully the cartoon can do it in a way that also makes them laugh or makes them think. That's what I believe I've been doing for 34 years, 25 of those being at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

So it's surprising to me when, after all those years, they go from saying “Hey, you know, that great job that we told you you've been doing, that great job that led us to match an offer from another newspaper that was trying to take you away from Pittsburgh," now this same paper is suddenly saying, “We don't want you to do that anymore.”

That really hurt. I feel like it became personal at that point. But in the end, I'm not really so worried and upset about myself as I am for the readers of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, who are now getting this kind of mish-mashed, right-wing, one-voice-only on the editorial page. This is seeping into other parts of the paper as well, with how stories are placed and emphasized. This is incredibly dangerous because it is being done to make the president look better.

Why did they end my employment? The only real way you're going to get an answer to that is to get inside the head of John Robinson Block, the publisher. He's the one that had decided that back in 2015, when Trump got into the race, "I like this guy, and even though we've been a traditionally liberal paper, we're suddenly going to start pushing towards an endorsement for Trump." It wasn't just that they didn't want me to draw hard-hitting cartoons about Donald Trump. They wanted me to soften them in a way that would make it a much more conservative cartoon or editorial page.

How did you make the choice to stand by your principles and not sell out?

For me it was about balancing the weight of allowing the editors to do their job and them trying to make me into somebody I'm not. My previous editor worked with me to make my cartoons better, to do some give and take. If I was maybe covering something that was a little too controversial, massaging it so the publisher wouldn't kill it, but doing so while not watering down the message, I could keep my integrity and that was really important to me.

They're trying to frame it now that I was not willing to collaborate and I wasn't good to work with. Frankly, that's just not true. All you have to do is look at all the times that I was trying to cooperate with them, all the sketches that I threw away and started over many times over the last three months. But what it came down to was they wanted me to muffle my voice in a way that I had never done in my 34 years as a cartoonist.

I would have to make a choice, and that choice would be to do cartoons that were sort of funny, but not offensive in any way to Republicans or Democrats or anybody. They didn't actually mind if I made fun of the Democrats. One of the reasons I blame this on Trump is because if Hillary Clinton had been elected president none of this would have happened. They would have been happy with my cartoons about Hillary because I would have been hammering away at her and there wouldn't have been this pro-Trump standard.

I think for me the moral decision came down to this: If a political cartoonist doesn't believe in what he or she is drawing and saying in a cartoon, then where in the paper can you believe anything? I just felt like I owed it to the readers, I owed it to myself and I owed it to all the fans that I have out there that don't even live in Pittsburgh to do the best work that I could.

This is especially important in a time where we have a president who doesn't believe in the rule of law, who doesn't believe in telling the truth and who believes that the media is the enemy. I felt like there was no way that I could go soft on him. It was clear that's what they wanted, because they were killing cartoons that were too hard on Trump. Management would then allow some cartoons to get in that were not about him. Then the situation reached a peak with the final week, where they killed everything I submitted and I just thought, “OK, they're trying to push me out.”

Was there any one moment? At the end did you just say to yourself, “I'm just going to do what I'm going to do, they're going to kill it anyway, let the chips fall where they may"?

When the editors killed six in a row -- and that has never happened to me in my entire career. I've never had two in a row killed, let alone six. I've had two or three cartoons a year killed, and that's a normal year for me. That's part of the game because I do make adjustments when the editors asked me to, and I will change some things. But then I'll also stand up for ideas, and if they get killed, it's usually because the cartoon just goes too far for them and I wasn't willing to change it. It doesn't mean I lose my job. It just means that's one of the submissions that gets killed in a given year.

But this was six in a row, and when it hit number four, I was like, “What's happening here?” and at that point, I just started drawing for the rest of that week. The next two that I drew I didn't even preview or pitch them. They were both about Trump and likely to get killed anyway, so I figured, what do I have to lose?

One of those cartoons is making the rounds right now. It is the cartoon with the immigration sign and a crossing where the family is running, and there's a silhouette of Trump grabbing a baby. By the time we got to the point where I went public with this, they had killed 10 full, finished cartoons and nine cartoon ideas. That's a lot.

How can you write a comfortable story or do a comfortable editorial cartoon about children being stolen from their families? Or about this man's sexism and racism? Because that's a really important point. The truth is uncomfortable by definition. The truth is nasty, the truth is ugly.

I think that that’s what they wanted me to do, and you just can't do it. You can't do it and still save face. You could write about it in that way if you're working for Fox News, of course, but I couldn't do such a thing. I knew that was what they wanted. I felt that I'm not going to be able to sleep at night. I'm going to be questioning what I just submitted to the paper if I do that.

In the beginning, when I started at the paper, the arrangement we had was that if I get something killed, I can still send it out for syndication. It just won't be in the paper. They agreed to that. When the editor first started killing all those editorial cartoons, they were still going out for syndication. The public was responding positively, and people were still saying, “Yeah, great cartoon,” and management had to hear about it. That was the other part that they didn't like. People were enjoying my work. Management was trying to stop it from happening.

I know it's their newspaper. I know the First Amendment protects them and not me in terms of my job. I can go out on the street or on Facebook or on Twitter and say whatever I want. That's where the First Amendment protects me. In terms of me saying whatever I want on their page, the owners have the right to say whatever they want in their product.

But I also know I have a responsibility to that audience and to myself. One would also think that the owners and management would recognize the value of a 25-year career where people are following me regularly and writing in and saying how much they love my cartoons. You would think that the owners would say, “OK, yes, we're changing our opinion page and position but maybe what we do is add some conservative cartoons on the page and move him over to the op-ed page so we keep the value that he adds to the paper.”

They didn't want to do that. I don't know why they felt that it was more important to get me to change who I am rather than just move me over. It especially doesn't make sense in this economy, because the newspaper is getting cancellations and lots of other flak for this.

Where did your moral courage come from?

I've been pondering that myself. My wife and I don't have children, but if we did this may have been a different decision. I knew I could take the stand because we looked at our finances and we said, “It's not going to be great, but we're going to be OK.” That's really important to know. Not enough people in this world have that opportunity, and they have to stay in jobs where they're treated poorly, where they're bullied, where they're sexually harassed. I think that's really horrible, because it's liberating to be in a position to say, “If this doesn't go the way I'd like it to go, I can walk away.”

That said, it was still a tough decision. When I look back on my life, the explanation has to be my family. My father and my sister were both very fierce advocates for what was right. I remember my dad sitting me down when Watergate was heating up. I was a kid. I still remember him saying, “Turn off 'Gilligan's Island' and watch this,” and I was like, “Ah, I don't want to watch this, this is boring. Just a bunch of old people talking.”

I didn't really get much out of watching it, but I did a lot out of him saying, "This is important and you need to pay attention to this." So that's where we are now. We're in a place where we need to start paying attention to all that is happening with Trump and his movement in this country. We can't ignore it. We can't let Trump have a pass, that's for sure.

In this moment, when a guy who already seems like a cartoon character is president, how do you separate the hackwork, the easy, obvious stuff, from more nuanced and sophisticated work?

The important part of any creative process, I believe, is to not go with your first idea. You need to realize that if I thought of that so quickly, then maybe others have thought of it too. So that's a good way to avoid the obvious, but then it's just constantly working and the more you do it, the better you get. I have often been so happy when I pursue the not-so-easy road and redraw or re-caption a cartoon, and it always turns out better.

The funny thing about political cartooning is, yes, there are many tempting clichés, but sometimes those clichés are the best metaphors. With Trump it's really difficult because he is a caricature already. It's our job to exaggerate him to the point of disbelief, but with enough truth that it is funny and still rings true. With him that's so difficult because everything he does is beyond belief. He's almost impossible to caricature. You almost have to find another way to get to him because just making him look like a buffoon is not enough. Trump already does that for himself.

What would have been the challenges if Hillary Clinton had won the election?

One of the challenges with Hillary is that she's a woman. It's harder to be as vicious in the drawing with women and with minorities because there's a fine line between caricature and sexist or racist ridicule. So you have to be really careful. On the other side, she's so well-known that there would be an ease with it too. The public knows that she is a tough, good politician. Some people think there's no tenderness there, but we've seen it in a few moments. I think there would be plenty to do. A woman president would be an interesting target for a cartoonist.

How did you navigate that with Barack Obama, given America's history of racial stereotypes from race minstrelsy to calling black people apes and gorillas. Is this where Obama's ears come in?

You have to balance the likeness with the exaggeration. With Obama, I think people were leaning more towards the actual likeness and less grotesque caricatures. Part of that, as you hinted, is because it would be racially insensitive to do it the other way. But also, every caricature is a journey, and every time you start to draw somebody, you start to figure out what things work and what things don't. It becomes a journey, and you eventually arrive at this place where you say, “OK, that's it. That's my vision of that face, that president.” It's always interesting to see what similarities cartoonists cling to, but how different they can be as well.

Given the controversy about her appearance and what is appropriate to mock, what would you do with Sarah Huckabee Sanders?

The funny thing is, I haven't really drawn her yet. I drew her predecessor a lot [Sean Spicer], and he was a fun target. I've seen other artists who handle it very nicely. She has those sad eyes. It is a tough call. You have to figure out how to say something in the drawing because it is more than just how they look but what they exude in terms of their moral character. I do think that some cartoonists have taken license with that, and I think they've done an OK job with it.

What's next for you?

Right now I'm in a maelstrom of goodwill from people, and I’m getting a lot of freelance offers. So I have to sit back and get my breath and look at all of that and take it in seriously. In the meantime, I want to keep drawing because I think this president needs to be held accountable. So I'm going to continue to draw cartoons for the syndicate and then see what the next thing will bring. I think it's important to just continue to be who I am, and that means at least three times a week I'll be drawing cartoons about politics.

What gives you hope for this country? What causes you the greatest concern at this moment?

Well, the greatest concern would be what happened to me at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette happening everywhere else to other people who are reporters, journalists, cartoonists and the like. This country is turning into something that we never have been. It's really ugly and that scares me. What gives me hope is that there are still a lot of people out there who believe the same thing I do: That we are better than this and that we should be electing people that are better than Trump. There may be a time when we can look back on this situation and see it more as an aberration than as a trend. I do think that there are enough people out there who believe in the good American story, and I think that's going to be important.

Shares