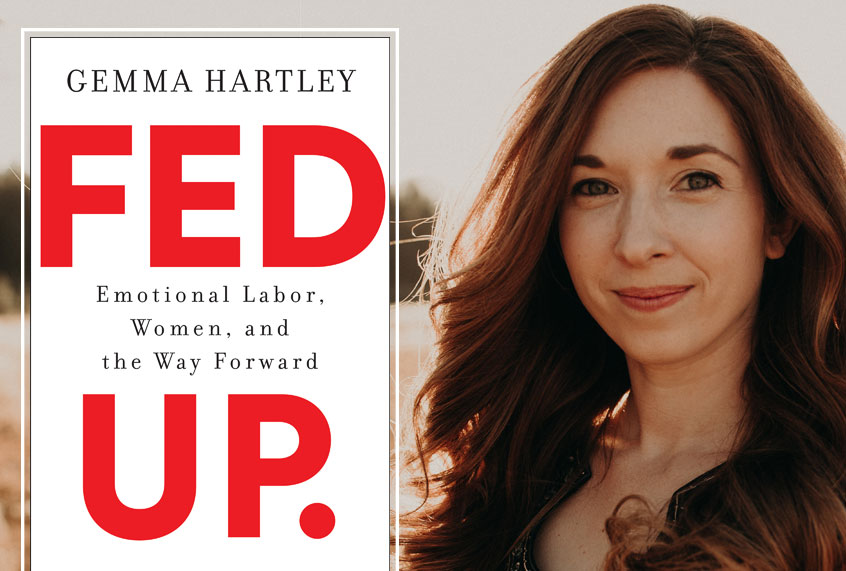

The number one accessory women are carrying around this season is their fury. Not that female anger is a new concept — we’ve been simmering for eons — but the articulation of our frustrations has made for some great recent literary fodder. The past several weeks already brought us Soraya Chemaly’s “Rage Becomes Her” and Rebecca Traister’s “Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger.” Now, a year after her supremely relatable Harper’s Bazaar story on women’s emotional labor went viral, Gemma Hartley has put expanded on her argument in a wise and realistic new book. Appropriately titled “Fed Up: Emotional Labor, Women, and the Way Forward,” Hartley writes from the grounded perspective of a working mother of three who knows exactly the toll of the invisible work of keeping all the ships running smoothly.

But it’s not just a tome for mothers — it’s a call to action for every woman who’s had someone else’s drudgery dropped in her lap, an acknowledgment of the heavy lifting of simply building a home life. Salon spoke recently with Hartley about creating more balanced domestic dynamics — and why becoming the poster girl for emotional labor didn’t magically transform her own life.

“We’re trying to move the needle on something that has been set in stone for hundreds of years,” Hartley tells me. “It’s not an easy thing to do. With my husband, it’s a totally new concept for him. We as women are just now finding the language to talk about this, and then we’ve got to have the language to talk about it and then bring men into this completely foreign concept. It takes a lot more work than just, ‘Oh I get it now. I can explain it now.'”

Another challenge is that the task of reforming things still falls upon women — men haven’t exactly shown themselves to be eager to upend the status quo. “That’s the Catch-22 of emotional labor,” she says. “We have to be the ones to initiate that change. It’s very frustrating to have to keep carrying that burden to see any change. That is really where that anger and that frustration rises up from. It should not be this way. We should be able to expect an equal amount of initiative from our adult partners. We shouldn’t be having another child added to the family in our partners. I think that’s really what my book comes down to.”

That equal initiative frequently doesn’t manifest. Instead, research suggests just the opposite to be the case — men will deliberately do a poor job with a household task so they can be relieved of it. “In one particular study from the UK, men actually admitted to doing chores badly so they wouldn’t be asked to do them again,” Hartley says. “Not just not taking the initiative, but doing a bad job so they would not have to.”

And here’s where women need to step back and not be our own worst enemies, too. “Sometimes women infantilize their husbands to such a degree,” Hartley observes, “that it’s not men being malicious and deliberately doing things wrong, but women just assuming that they’re going to do things wrong. I just want to shake people when I hear that. He’s not going to step up and say, ‘How about I put a little bit more on my plate right now?’ It’s that self-fulfilling prophecy that we’re putting in place when we say, ‘He could never do what I do.'”

Of course, the pressure on women is intense. Dads are still generously regarded as “babysitting” their own children; a woman whose spouse cooks or cleans up is “lucky” rather than merely living with an equal partner. But “we shouldn’t be comparing our partners to the worst of our mediocre friends,” says Hartley. “The standard that you’re setting in your home should be between two equal partners. Just because we have it better than the next woman doesn’t mean that we can’t want more for ourselves and for our relationships. It’s not an unhealthy thing to want more.”

Hartley knows that wanting more is easier than asking for more, though. “There is this expectation that we should be doing emotional labor,” she says. “When we don’t, we feel like we’re doing something wrong. There is this social status that comes with being the woman that has it all, that has it all together, that keeps everything running smoothly. We have this desire to be perfectionist in that way to get everything done and to feel completely competent and in control of everyone’s lives, not just our own. It’s really hard to give up that gold star for doing all of the emotional labor.”

The upside of doling out the workload extends to men and kids. Surprise — competence and empathy are good for everybody!

“We talk about it like it’s a lot of work and it’s a burden — and it is when you’re doing all of it,” Hartley says. “When it’s more equally shared, it really benefits both parties. With emotional labor, we talk a lot about the surface stuff, the noticing what needs to be done in the house. It goes deeper than that. It’s about noticing what other people need. It’s really the work of caring deeply about how people around you are living and how they are feeling. That is a skill that we don’t cultivate in boys, and it’s one that we really should because it impacts their relationships both with each other and with their partners. When people are normalizing the equal splitting of emotional labor, it’s good for everyone. You don’t have to have kids in order for this to be a good thing for the future of our culture.”

This, precisely, is why does the conversation about emotional labor matters so much. Because it’s about respect. It’s about being seen. It is a thoughtful, adult act to cohabit with someone in a way that acknowledges shared responsibility, that recognizes the effort of making the doctor appointments or changing the toilet paper.

“The most favored argument of all of the men who came after me after I wrote that original article was that ‘You are just a control freak. Your standards are too high. No one could live up to your expectations.’ I don’t think that’s true at all,” says Hartley. “I don’t have unreasonable expectations. We are just so used to feeling that if you want things done a certain way, you need to do them yourself. We do have to go into that perfectionism and see where we might be overdoing it a bit. But by and large, women that I know don’t keep immaculate houses or have these really unreasonable standards. It’s keeping everyone on track, everything running smoothly.”

“I think that when you say, just give it up or do it yourself, it’s really devaluing the work that women do when they take on emotional labor,” she adds. “It’s saying that this work is not important and that we don’t need it, and that’s just not true. When you are raising children they’re not going to thank you for what you’re doing and they’re not going to notice all of the things. That is natural; that is how it should be because kids are little narcissists. It should be different with your partner. You should have mutual respect. You should have shared responsibility, and that is not the case for so many women.”

“It seems so basic,” says Hartley, “because we’re so used to going deep and really caring about the lives of others. Men need to do that, too. It really will bring them more fully into the human experience when they have these skills of emotional labor. It’s a really essential skill. Even those menial jobs like the noticing the socks on the floor, the laundry, can be really satisfying. It really just makes you more grounded in your life when you have these new experiences other than ‘I go to work and do my job and come home and don’t take care of anything unless I’m asked.’ There’s so much to be gained by going deeper to really experiencing what it’s like to live with emotional labor as a part of your daily life.”

Yet the resistance to change runs deep, especially when it befits the patriarchy to assume that if only women are saying there’s a problem, it’s not a legitimate issue. “So much of the recent literature has said if you don’t want to nag or do it yourself, just let it all go. But that’s also not a great option, because it’s saying that the onus is on you to either drop everything or figure out a new standard,” says Hartley. “It’s not changing the dynamic in your relationship at all. It’s not demanding any growth from your partner. I don’t think it should always be on women to be the ones to step up and find the solutions and make everything work while men sit around and do the same thing.”

Whether they’re in our couch cushions or our relationship dynamics, there’s no reason for women to settle for crumbs any more. “I think we are so conditioned against speaking up when something is wrong,” Hartley says, “especially when we’re in good relationships — because we should feel lucky that we have someone who takes up a good equal role in parenting or someone that doesn’t make you stay home and do dishes all day. We should be grateful for crumbs.”

But, she says, “Society wouldn’t have made much progress if we had always been content with the crumbs that the patriarchy told us to be happy with. You’re just going to be stagnant if you don’t demand more.”