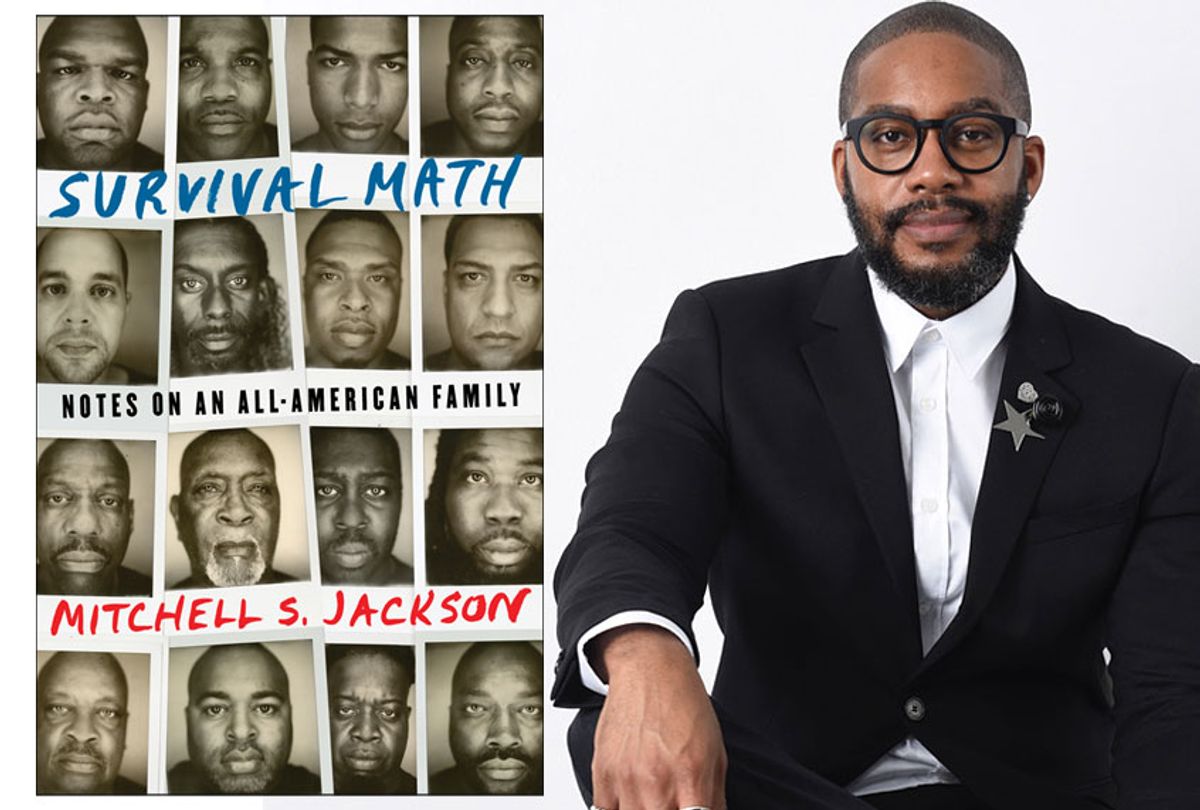

Shared struggle and collective survival form the core of Mitchell Jackson's latest book, "Survival Math: Notes on an All-American Family." The cover image features rows and columns of Jackson's photographs of his family members, whose anonymous stories he dubbed "Survivor Files" and interspersed throughout his memoir. "The narratives of the men in my family are separate from the narratives in the essays," Jackson writes in the author's note. "But they are one with the story of black Americans. We are all-American, which is to say, our stories of survival are inseparable from the ever-fraught history of America."

At first glance, Jackson's writing style and his life trajectory are defined by a straddling of multiple and seemingly contradictory worlds, yet in "Survival Math," Jackson powerfully disrupts various binaries, showing how academic scholarship and accessible writing can merge, how empathy and accountability can overlap, how self and social critique are interconnected.

In a recent interview, Jackson discussed his writing process, the essay that angered his editor the most, and how truth-telling is the connective thread in his work.

You're writing style is so unique — it's poetic, but really clear and has this unique cadence to it. Musically, and literary-wise, who are the people that have shaped your style?

One of them is John Edgar Wideman, I really liked a lot of his later works. . . One of my favorite books of nonfiction is "Brothers and Keepers," which is about him and his brother who are doing life in prison. But I really love the way that he captured his brother's voice. He sounded very much like my uncles and some of the guys I grew up with.

And then, I actually hear my uncles, and my stepfather, and the kind of men that I grew up. As far as the voice, [that's] who I hear most when I'm trying to compose — even borrowing their diction, their cadence, the rhythm of how they say what they say. So there's literary influences, and then also just minding the language of home.

Right. The "Composite Pops" in your life, as you write. I'm also just curious if you were listening to any specific artists or albums while writing "Survival Math." I don't know if that's part of your process, but it's kind of musical in a way or rhythmic, even.

It isn't a part of my process. I can't listen to music while I'm working.

But what I do sometimes is listen to music that was made during the period in which I'm writing. So when I was writing, let's say, "The Scale," I would go back and listen to old Too $hort or old 2pac. I was sometimes quoting it, but I wanted to remember the kind of language. I wanted it to put me in places where I used to listen to the music when I was young. I don't know if it necessarily influenced the voice, but it does put me in the place that gives me access to memory.

In the book, at various points you're addressing your children, distant family members, friends. I'm wondering if there's a specific reader or audience that you're speaking to?

Yes. I think I'm really interested in speaking to a person that's, I guess like myself, who both has some kind of connection or — a genuine connection to, let's say — I hate saying urban America, but to that kind of environment. But, then someone who also is in some way connected to the literary world or academia, who has these kind of concerns, which exist in the academy and has access to that kind of language. I'm always trying to put those two things together, and then really speaking to the person that stands at the intersection of them.

Can you talk to me a little bit about the title and also the subtitle, "Notes on All-American Family"? It made me think about the recent Esquire cover. I don't know if you saw it, but just the types of people and stories that are always default for "American."

Yes. I didn't see the recent Esquire story, so now I'm looking it up. Was it last month?

It's the March cover, but it's of this 17-year-old conservative white kid.

"An American Boy." Oh. OK.

Yeah. Exactly.

Now I see it.

It's interesting, the juxtaposition of your work coming out the same month.

Well, that is why I chose that subtitle, because I think that when we talk about what it means to be American, we often leave out these kind of stories or stories about these kind of people. And so, I really wanted to kind of challenge that idea of what it means to be American.

In "American Blood," I even make the case that people who have been marginalized are maybe the most American, because they are able to maintain a kind of sense of national pride, while the nation kind of puts them under their boot. It's a lot easier to feel national pride when you're exalted like this guy on the cover of Esquire.

"Survival Math" just came from me reflecting on experiences — that I was really doing some calculus in order to escape harm on a number of occasions, and then me kind of reflecting and saying, "Well, if it happened to me it must've been happening to other men in my family, because we were all living in the same area."

And I was right.

The book is like this collection of different types of writing. There are parts that are like journal entries, letters, parts that are really conversational. There are these really robust historical and religious references, "Survivor Files," and I think it's so fascinating how the writings are coupled by themes that feel simultaneously broad and personal. What was the writing and curation process like for you? Did you start with themes and organize later?

Well, I initially started with a few essays, and then at a certain point I figured out that the title was going to be "Survival Math."

Oh, wow. You figured out early?

Yeah. And then, once I figured out it was going to be "Survival Math," I knew that I wanted to figure out how to include other stories of survival, and so that's when I came up with the idea to photograph the men in my family and write their stories.

I also wanted to give them a sense of anonymity. I knew they had gone through some tough things and I didn't want this as a trail in their life, so that's why I ended up using the second person and not identifying them. My editor and I actually said, "Well, how are we going to organize this?"

We started asking ourselves questions, and then through that kind of conversation I was like, "Oh. Well, each section is going to be answering a question." And then, really, really late in the process, like actually right before I handed in maybe one of my final drafts, I decided that I wanted to frame the really personal stories with the historical context.

That's where I came up with centos and went and researched all of those documents, because I said I think it's really easy to kind of dismiss these as, "Oh. This is just what's happening now in this particular place," and to disconnect it from the history of this. And so, I wanted to do what I could to discourage people from doing that and that's where the centos come in.

It's like, "No. I'm taking the language of America's history and using it to frame these really personal stories."

Right. And bringing it into context, this violence in many forms as a historical legacy of America. I thought that was just fascinating. How did you go about kind of collecting these very detailed, at times painful stories from people in your family, not just in the "Survivor Files," but really sprinkled throughout?

Right. Yeah. I mean, I'm just very fortunate. I think one of the things that helped me was I would always share something personal with whomever I was interviewing. And also, because I had relationships with all of the people that I interviewed, I think they already had a certain level of trust in me, and I tried to do what I could not to violate that trust, and to remind them that I was doing this in good faith, and that it was kind of serving a purpose that was bigger than us.

I do think that them sharing their story is going to make a difference for someone else, and so that worked out. But, it was still almost shocking sometimes to hear stories about people that I knew very well, people that were my blood kin and to hear them and go, "Well, where was I? Why didn't I hear about this? Why wasn't I there to help you?"

But, it also made me feel like I was creating a ledger of family history. And so, that part made it feel very necessary.

Yeah. It's interesting where you start the book writing to Markus, who died in 1788 and was the first documented black person in your hometown of Oregon, and then thinking about this overall goal of creating a family history. How given America's history of kidnapping black people and erasing their stories, that's a radical act to document.

Yeah, yeah. I agree.

Your first book is fiction. How was the transition from fiction to memoir?

Well, my first book was an autobiographical novel, and so I think it was an easier transition for me to move to nonfiction. Also, I worked as a journalist for a very long time. I did a lot of hip-hop journalism and sports journalism, so I was used to interviewing people. I was used to figuring out very quickly the kind of structure that I needed for a particular piece of writing, so I think all of those things served me well.

But, I think what really served me well is this kind of imperative in my work to tell the truth. And so, that exists across genres. All of my stories are born of some kind of personal experience. No knock on anyone who's Afrofuturist or likes romance or some other kind of genre, but I'm in the genre and the spirit of realist or naturalist fiction, and so I think that lends itself to memoir and essay.

I was reading that you started writing your own story while you were in prison. I'm wondering if some of that writing made it into "Survival Math"?

No. That writing became "The Residue Years." But, I guess some of it actually did make it to "Survival Math," because I talk about that experience in I think it was "Revision."

It's all of a theme to me. This theme feels very much like the kind of brother of "The Residue Years." As "The Residue Years" is like my particular or immediate family, the story of my immediate family, and then "Survival Math" is like the story of my extended family. But, also the story of my community. So it's like dialing out the lens a little bit and really trying to figure out how we got to the place that I wrote about in "The Residue Years."

I thought the addiction/marriage metaphor was really compelling, I'm wondering if you feel like they're interconnected in some way or do they share emotions or actions that stand out to you?

I think I just started out trying to examine why my mother struggled so long with her addiction, and then at a certain point I was like, "Well, I mean what if we can look at it through a different vantage?" What if I can take a step back and say, "Well, she has been almost committed to this life for a very long time."

I don't remember how I started thinking about it in the context of marriage. Maybe because I was already thinking about commitment, and then that just led me into researching the history of marriage. It did operate like a long-term relationship with my mother and the thing about bad relationships is you kind of never know when you're gonna go back to that person. They can sweet talk you, and then you're backsliding. That's the way that addiction has worked, at least as far as I can see in my family.

I really appreciated the section on the broadness of violence against women, and how you really held yourself accountable for your own mistreatment, and also asked the women in your life for consent to tell your side of the story, as well as allowing them a place to their own. I'd never seen that. I'm wondering if the #MeToo movement has helped you think through this process of how "Men on the Scale" can seek restitution?

The heart of that essay was started, I don't know, 2011/2012. It was well before I knew anything about #MeToo, and so I was already of the mindset that there needs to be a reckoning. But I finished the edits on the essay while #MeToo was — I don't want to say it was at its apex — but it was very much a part of the kind of national conversation.

And so, it's interesting, because I started thinking about this well before it came, but the movement shaped how someone would receive it. I'm very much aware of that, to the point where I'm like, "Is this the right thing for me to even be writing about now?"

If I was motivated by #MeToo to write this essay, then I probably wouldn't put it in, because it would have felt disingenuous. It would've felt like I was trying to catch a wave that I thought other people were already interested in. But it felt like I was already committed to telling the story well before that came. So, it felt like a necessity for me to kind of work through this and this took the longest of any essay that I've ever written and more drafts. It also angered my editor in a way that I had never seen before. And so, I also took that as a challenge to figure out how to do it and ultimately, it was adding the voices of women to it that I think kind of shifted it into the place it needed to be.

What angered them about it?

I mean, just hearing all that I had done. I have a woman editor. . . At first, I didn't have any of the women and I think it felt like hubris. You know? Like I was proud of this and I wasn't, but I could see how she could receive it like that.

So, I really had to go in there and think about what I was saying. I hadn't done the research yet on types of violence and why one might consider this a type of violence, even if it's an emotional violence. And then, also I think I had to figure out the right balance of historical research, because I didn't want it to be like I was shifting blame to history. But, also I wanted to acknowledge that this does come out of a kind of way of thinking that predates me and my cohort.

I really appreciated just the total laying out, because it felt like ownership of what you've done and I feel like that's often what is missing when men are doing these kind of apology tours, is an unwillingness to reckon with what exactly happened and what harm that caused. I thought was really powerful in a way where it was like you were unafraid to — not in a disrespectful way — but to humiliate yourself. It was just brutally honest and I feel like that made me think, "OK. Someone can begin to heal from here."

Mm-hmm. Yeah. Well, one would hope.

Right and then, knowing that you had consent from these women to share their stories made it also more grounded, too. I also thought was really interesting when you talk about your grandfather and his ultimately fatal abuse against your grandmother. You get into ideas of restorative justice, in both acknowledging that he shouldn't be reduced to a single act, no matter how horrific, and also that he's faced and sought penance. I'm wondering if your own experience with the excessive and disproportionate punishment of the criminal justice system has affected your ideas around justice?

Yes. My personal experience really shaped it.

When I was in there, I remember I got transferred from a minimum to a medium security [prison] and the first day I walked in there was this guy sitting on a bunk and the way that he looked at me was like he wanted me dead. I didn't know who he was, and so I asked one of my friends. I was like, "Yo. Who is this dude?" They were like, "Oh. He in for murder, but he about to go home." He had done like 16 or something years and he was about to go home.

But later on he and I just started talking. And then, we started chatting, like really having conversations about what we wanted to do and what his objectives were. And then, he left maybe four months before I went home and he was one of the first people to write me a letter when he left the prison. At that point we were friends and I was like, "Man, this guy was looking out for me, wanted me to feel safe, to feel acknowledged." I was like, "Yes. He's done this terrible thing, but as far as I can see he wasn't that person."

And so, many instances like that really instilled me with the belief that we have to be able to figure out how to let people make amends, and then make some positive changes in their life.

Yeah, definitely. The book, to me feels really grounded in this unwavering empathy and honesty in regard to the people in your life, and also, it reminded me some of Kiese Laymon's "Heavy," in terms of this real sense of strength and bravery when it comes to self-critique and ownership. You're not writing about yourself in this pseudo self-deprecating way that's actually self-aggrandizing or meant to be charming, but truly brutally honest. That can't come from just writing, but serious reflection and accountability of one's power and consequences. Is there anything you can share with me about what this process has been like for you? How "Revision," as you talk about in multiple ways, has shaped this book?

I mean, I think its really been the most important lesson that I've learned thus far. But, the overall lesson of it takes assiduousness. I had to keep at it, and keep at in. There isn't anything in here that wasn't revised dozens and dozens of times.

Also, I learned that I would start with an idea and think I knew something, but then I would do research and I would do all different types of research and I would figure out that, "Oh. I have to go further." And so, it really made me have a lot of respect for the process of making something.

And then, being open to reflection, and revision, and not being so grounded or stringent in my beliefs or where I thought something was going to go that I couldn't revise it. So all of those things are important in making something, in this case a book. But, I think they're also really important in living a life. If I had just maintained the same kind of cultural values that I had at 21, I would be in really bad shape now at 43.

Do you think as a writer it's essential to reckon with our own personal experiences and our own humanity?

Yeah, I read someone talking about how they didn't want to write about themselves anymore and I guess I understand that to a certain degree, but I feel like we're always writing about ourselves no matter what and I would be kind of apprehensive about saying that I was moving away from the self.

Even if I was writing a genre or writing about spaceships, I feel like you have to really interrogate what your values are, what your morals are, what you're willing to do and not do, how you see the world, why you see the world, and I think that, that is at the core of everything that we make.

Which, reminds me of Toni Morrison, where she was like, "I don't believe in arts for art's sake." She was like, "Every piece of art is political, you're always saying something about the current political moment." Sometimes you're saying you don't want to change it, in which case you're saying, "No. This is just art." But, then in other times you're explicitly speaking to some kind of political question.

But, I'm of the mind that it should be both beautiful and it should be speaking to justice.

Shares