My teenage daughters and their friends are my role models. While some of my peers brag that they don't vote because "elections don't matter" and watch news of political corruption and mass shootings with a kind of resigned detachment, it's the students I know who are fearlessly, consistently getting stuff done. I'm not just talking about marches, although marches have their purpose. I'm not just talking about voting, although I couldn't have been prouder when my college student daughter texted me a selfie after she'd mailed off her first absentee ballot. I'm also talking about students testifying before congress about gun control. Lobbying for college tuition relief. Standing up and speaking up about sexual assault. Taking their health into their own hands.

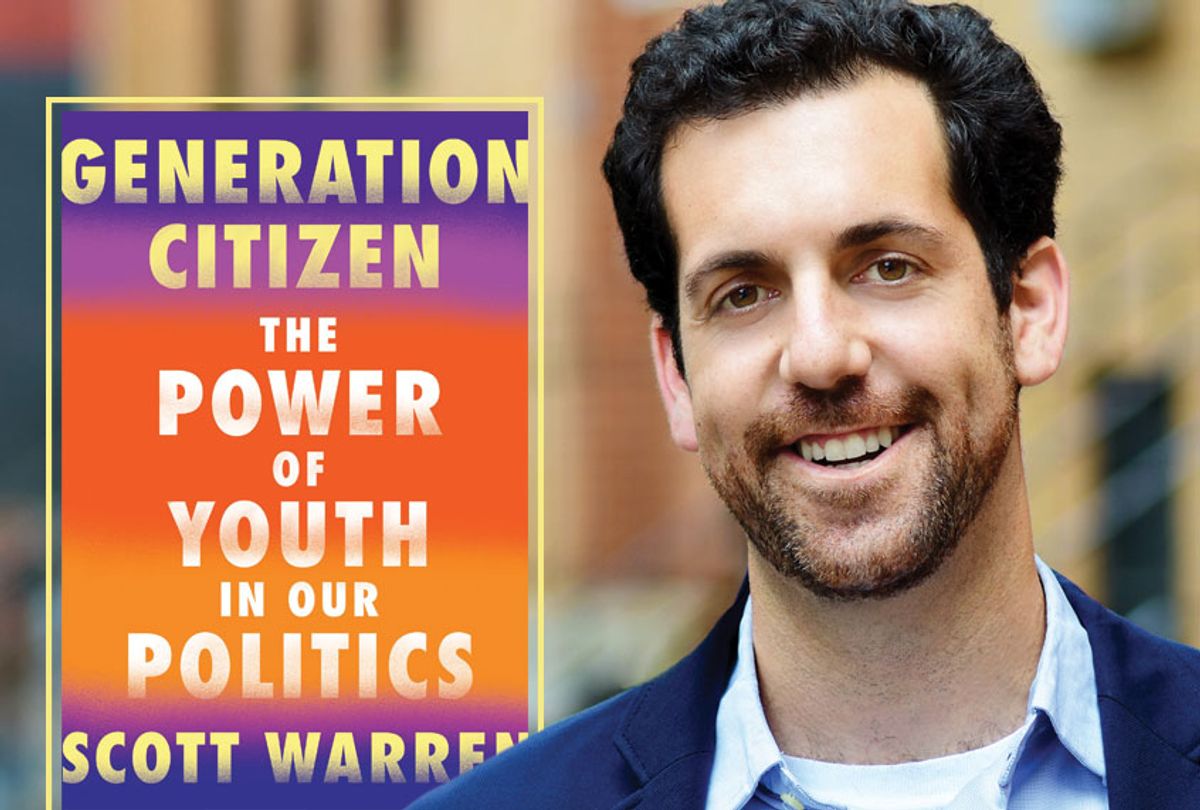

Scott Warren shares my hopefulness, and he's got a plan. As cofounder and chief executive officer of Generation Citizen, he's spent the past decade — since he was a college student himself — advocating, organizing and facilitating youth movements for positive change. He's now the author of a new book, appropriately entitled "Generation Citizen: The Power of Youth In Our Politics," and recently talked to me via phone about how all of us — whatever our age — can be more engaged inside and out of the voting booth.

As a parent of a recent first-time voter and another upcoming voter, this is a subject that's very dear to my heart. It was sad when you wrote about older people being discouraging and cynical about this generation coming up. I have so much hope in them. I have so much trust in them. Going to marches with my daughters, it just feels like I see this wave of activism coming up that is really, really different and really exciting.

So what spurred you to write this book right here, right now? You begin by talking about Parkland, bringing it very much to the front and center of present day. But you've been working in this field for over a decade. Why this guide? Why now?

I have always been, as I write about, passionate about this topic. I've been passionate about the power of politics and the potential of democracy for essentially my entire life. I have seen firsthand the power of what happens when young people, and the idealism that they have, help propel us forward. I think it's possible in this moment to inject, however difficult it may be, some positivity back into the potential and possibility for political engagement. It's easy to be cynical, and I do think that our democracy and politics are at some sort of precipice right now. There is a necessity for young people to become engaged right now. This book can help spur a conversation, can help spur a realization or a new recognition of the power of young people. I get to see this every day in my work.

We are in a unique moment in our democracy, in a post-Parkland moment. There is renewed interest in youth political engagement at large.

This is a book that's coming out in the lead up to the 2020 election. We saw what happened in 2016. We saw the difference in the election in 2018 in terms of young people getting out and voting. But this is not just a book about voting. That's a really important point that you make. It's not enough to just show up once or twice a year at the polls and think that you've done your civic duty. I'm wondering what you have seen, as someone who has been involved in this for a long time and who was involved in civic action before 2016. Was it a harder sell a few years ago? Was it tougher for you to motivate people before 2016? Or is it just that we as adults haven't been paying as much attention?

Generation Citizen was literally founded in the summer and fall right before Obama got elected. There was this energy behind politics then, in the sense of possibility. But even when Obama was getting elected, it was difficult for folks to take civics education and Generation Citizen seriously. I think we just put all of our hopes in that presidency and didn't think about sort of the ramifications of rebuilding a foundation. Whereas now, post 2016 election, there's a lot more interest in civics education and youth activism. I think some of it speaks to we have a tendency to react to threats, and we have a tendency to react to negative. We need to get more engaged now, whereas we might have felt that things for a little better before.

Voting is important but insufficient. In 2018, 32 percent of 18 to 29 year olds voted, which was much higher than the 18 percent of the last returns. It's still only 32 percent. The thing that I think about a lot is, "How do we just get this to be something that is an expectation?" Our politics would be completely different if young people participated, not just voted but participated, more. We do have an opportunity right now because there's more attention on it.

I want to make sure that we're seeing this as cyclical and not just in response to certain elections. We're also thinking about, how do we build the foundation that's not just in response to Trump or not just in response to Obama, but there is a broader perspective of, are we going to rebuild our democracy? We really have to focus on the foundations.

I could've written a fairly similar book about five years ago. I don't think it would have gotten as much attention. That speaks to the the fact that young people are always at the forefront of change and that they need to get involved. That democracy is a precipice is not new. The fact that people are realizing that probably is a little new. So that dynamic is sort of interesting to explore too.

If you know anything about history, including global history, so much of it is student-led. So much of it is youth-led. You can't have really significant positive change without a youth movement.

That's always been the case, and people still discount youth voices. They perhaps don't see them as relevant or actionable. It's almost the whole notion of re-learning history, and how we have to continually do that. I feel that to some extent with young people and youth activism or even with Parkland. There is this sort of [feeling of] oh, the young people are going to save us. Youth activism is not new.

Two of the points that you make are that we can't just have the "one story," and we can't just be reactive. It can't just be, "We're going to take to the streets" or, "We're going to address an issue, a foundational problem," when something erupts. We have to be working constantly. It's not just the case of one person who does one thing and we're going to respond to that. But the idea that you have to put in the time every day feels different.

And it's a hard thing to do. We have a tendency as society to glorify the individual and glorify the success story. We need heroic endeavors to actually get us from point A to point B. Inspiring people through the individual and the narrative is important — while recognizing that you literally cannot do it on your own. People talk about being able to only get to a certain place alone. Our culture has very much continued to over-glorify and -simplify that individual narrative in ways that can be problematic.

I think part of the apathy or the sense of helplessness that people often have about civic engagement is this sense of, "But I'm not a hero. I'm not a visionary. I'm not brilliant. What can I possibly do?" And you then break down, "Well, here's what you can do." I would love for you to give a little breakdown for of the hourglass concept.

The hourglass can literally be used for anything in life. The concept is breaking down complex issues, figuring out the root cause and then ensuring that there's a specific goal on the other end. That process is incredibly important for political engagement. We have a tendency to focus on the broader. Care about climate change? Go to a rally. Care about gun violence? Write a letter. If you just talk about broad aspects of an issue without going into detail, you're only going to scratch the surface.

The notion of that purposeful muddy middle is harder, but it allows you to really understand why something's happening, what the problems are and how to work at a more complex level. It doesn't mean that you have to understand every single issue to its entire complexity, but there is just an importance of really trying to understand things. There also can be a danger when you don't. If you're not actually understanding issues, there can be a challenge in terms of not carrying things to their conclusion too.

That speaks very much to young people who have a different set of distractions and commitments and responsibilities. It is hard to balance being a full time student and practicing your saxophone and commuting to and from school, and then finding time in your day to then also be an engaged and caring person. To really find and identify maybe one aspect of an issue and to start drilling it down to, "Maybe there's something I can do at my community level."

That local aspect of it is so important too, especially in politics right now, figuring things out in your community where your voice does matter. I was in a rural town in Oklahoma last week called Manitou. There's a lot of the same feelings that you would find in New York City, [students] feeling that their voices don't matter and frustration that the system's left them behind. There's power in recognizing the universality that young people want to make a difference, but they're frustrated. There's an opportunity right now to help push that narrative forward too.

Do you think that part of the challenge is that we live in a more siloed culture right now that it's harder to get out of your comfort zone and it's harder to engage?

One hundred percent. I think and I worry about this. The extreme polarization is one of the more challenging and pressing issues of our time. Social media and the internet exacerbate it. And I think our living habits exacerbate it. I do think it is valuable to engage with people who disagree with you. On a more macro level, that's something that we have to grapple with because a democracy cannot work if there's one opinion or one side that prevails over everybody else. The partisanship is significantly worse than it's ever been in. Figuring that out, it's going to be really, really important and really, really challenging too.

In the book, you are so straightforward in terms of who you are and where you are coming from politically. But you also then say, "This is not just about me and my personal politics. This is about how to become involved and how to become an involved citizen." That is something that all of us need to start thinking clearly and constructively about.

It would be inauthentic to write a book in which I'm talking about everybody getting engaged and make it nonpartisan. I include my own beliefs. It doesn't mean that my own beliefs are right. I think that's important to put in there too.

The key isn't, "How do I figure out how to follow Scott's path exactly like he does?" But, "How do I use these examples and ideas as a template for my own civic engagement?"

The only way this is going to work as if we all engage. Not if one person as an individual engages, but we all engaging. That I think is the collective puzzle that we have to try to solve.

If I were to say, "You feel cynical. You think it doesn't matter," what would you say is, "You know what, just try this. Just try this today"?

One thing I actually say is, just to talk to any young person. Their idealism is needed and necessary and a breath of fresh air. That's what I do. I am probably less idealistic that I used to be, but that's always necessary.

Then I think, focusing, focusing on an issue and going in deep on that issue. It takes time. That's one thing that I would also advocate for is for people to be patient. Look at history and look at how many times across history we've seen real progress. Becoming inspired and recognizing that this takes a while. It's never going to be perfect and that's partially what we have to realize too. But we keep moving forward. And that's one of the inspiring things that I've seen.

Shares