It appears the mainstream media — especially the political desk at the New York Times — has decided on its narrative framework for the Democratic primary campaign in 2020: There's a fraught and difficult choice between nominating an "electable" centrist or choosing a more progressive candidate who will motivate the base but supposedly will have a much harder time defeating Donald Trump.

Glenn Thrush of the Times is the latest reporter presenting the idea that a centrist is more "electable" as if this were an inescapable truth instead of a poorly evidenced assumption.

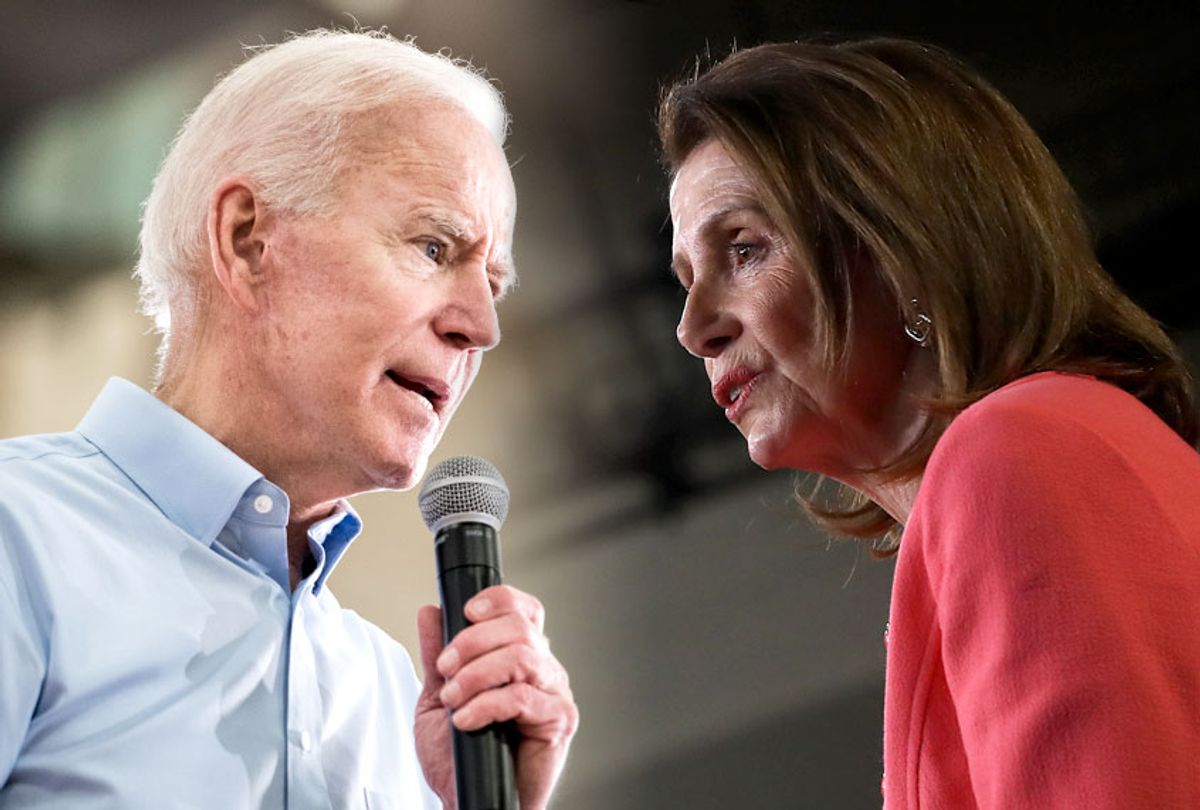

"Pelosi Warns Democrats: Stay in the Center or Trump May Contest Election Results," the headline on Thrush's weekend story blares. In it, he claims that House Speaker Nancy Pelosi's desire is to "not risk alienating the moderate voters who flocked to the party in 2018 by drifting too far to the left."

Whether or not Pelosi actually said that, or whether that's just Thrush putting some spin on the ball, is unclear. He only quotes her saying, "Own the center left, own the mainstream," and adding that Democrats won in 2018 because they "did not engage in some of the other exuberances that exist in our party," which Thrush defines as "'Medicare for all' and the Green New Deal." But he doesn't directly quote Pelosi mentioning either of those things, and considering how many Democrats who ran on Medicare or All won in 2018, it's hard to imagine she was actually arguing that phrase is political poison.

But regardless of what Pelosi said, the article's clear implication — that Democrats have to choose between progressive politics and winning elections — remains a sacred doctrine in mainstream media circles. There is no real evidence for this proposition. Yet this is precisely why former Vice President Joe Biden is being held out as the most "electable" candidate in the race, on the grounds that he appeals to the supposed moderate swing voters who are viewed as the key to a Democrat winning the White House in 2020.

The "moderate" voter in the pundit imagination is not all that well-defined most of the time, but taking a stab at it, I'd say what is being imagined is often someone like Biden: Economically more conservative than most Democrats but generally liberal on social policy, while occasionally saying conservative-friendly things about race and gender issues to reassure white voters that he's not too woke. The idea is that candidates like that will scoop up voters, mainly in suburban areas, who often vote Republican but are gettable because they're economically conservative but basically cool with issues like gay marriage and abortion rights.

The problem is that this category of voters, who would be called "libertarians" in political science circles, don't really exist in American politics. As Paul Krugman of the New York Times noted in February, these fabled economically conservative but socially liberal voters only constitute about 4% of the electorate. This is in contrast with the consistently liberal (45% of voters), economically liberal but socially conservative (29%), and the consistently conservative (23%).

If we're talking about people who voted for Barack Obama and then switched to Trump, they mostly fall into group No. 3, the economically liberal but socially conservative types — aka "populists" — who seemed to feel safe making the switch mainly because Trump was (incorrectly) perceived as posing no threat to social safety net systems like Medicare or disability benefits on which this group relies.

All of which is to to say that the "centrist" model for a Democrat has it exactly backwards. If the goal is to win over swing voters in Midwestern states, the winning strategy isn't to back an economically centrist candidate like Biden, but a Democrat who appeals so strongly to these voters with progressive economic policies that they're willing to set aside the racial resentment that led them to vote for Trump.

Incidentally, this is part of the reason why Obama won in 2008. A small but important percentage of populist voters stifled their racism and voted for the black candidate for economic reasons. But Obama also ran in a time of economic crisis, when those voters were extremely worried about the security of their jobs and benefits. With a relatively strong economy, it may simply be impossible for Democrats to win them back this time around — and there's no point trying to appeal to them on social issues. Even the most socially conservative Democrat is far more liberal than the most liberal Republican, so any strategic effort to appeal to social conservatives is likelier to alienate liberal voters than to accomplish its stated goal.

Even that argument is likely giving too much weight to ideology as a factor in winning elections. Political science shows there's surprisingly little causal relationship between ideology and party affiliation, and that people tend to pick parties for identity reasons and then shape their political views around that. That's why Trump, who started out as a bitterly polarizing figure in the Republican Party, now has near-complete support from Republicans. Even if they were initially skeptical, it was easier to get on board with Trump than it was to abandon their identity as Republicans.

There are many fluctuating factors in play that make it nearly impossible to say for certain what an "electable" candidate looks like, one thing that's worth noting is that both Obama and Trump were able to garner a great deal of media attention by being something new and different. (Indeed, this might be the only quality they share.)

In Obama's case, it was not just his race, though that certainly mattered in terms of making the 2008 election seem historic. It was his personal charisma and his upbeat campaign style, which struck a strong contrast with the misery inflicted by eight years of George W. Bush, but also with the milquetoasty, triangulating style of the Democratic Party at the time. Obama was not actually on Hillary Clinton's left during the 2008 primaries — at least not on policy — but he was perceived as such, particularly since he hadn't supported the Iraq war, unlike the milquetoasty, triangulating Democrats. He was able to define himself as someone bold and interesting, which John Kerry was totally unable to do in his 2004 campaign against Bush.

Similarly, Trump, hateful monster that he is, was able to cast himself as a decisive, bold figure who was not given to compromise and would shake things up in Washington. That helped generate enough enthusiasm among the declining Republican base to drag him across the finish line.

What these elections demonstrate is that voters aren't really inspired by playing it safe or moving to the center. Instead, candidates do better by convincing voters that this election is a historic moment and they don't want to be left on the sidelines. There are a number of 2020 candidates who have that juice for different reasons: Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Pete Buttigieg and Kamala Harris all seem to be generating excitement at their rallies. It could be catastrophic if Democratic voters, laboring under the panicky delusion that only a "centrist" can win, blow their chance to beat Trump by nominating exactly the wrong kind of candidate.

Shares