In 2005, writing for True West magazine, I asked "Deadwood" creator David Milch when he thought the series should end. He replied, “Buffalo Bill once said ‘When the railroad comes, the story is over.’ The railroad brought civilization to the West and tamed towns like Deadwood.”

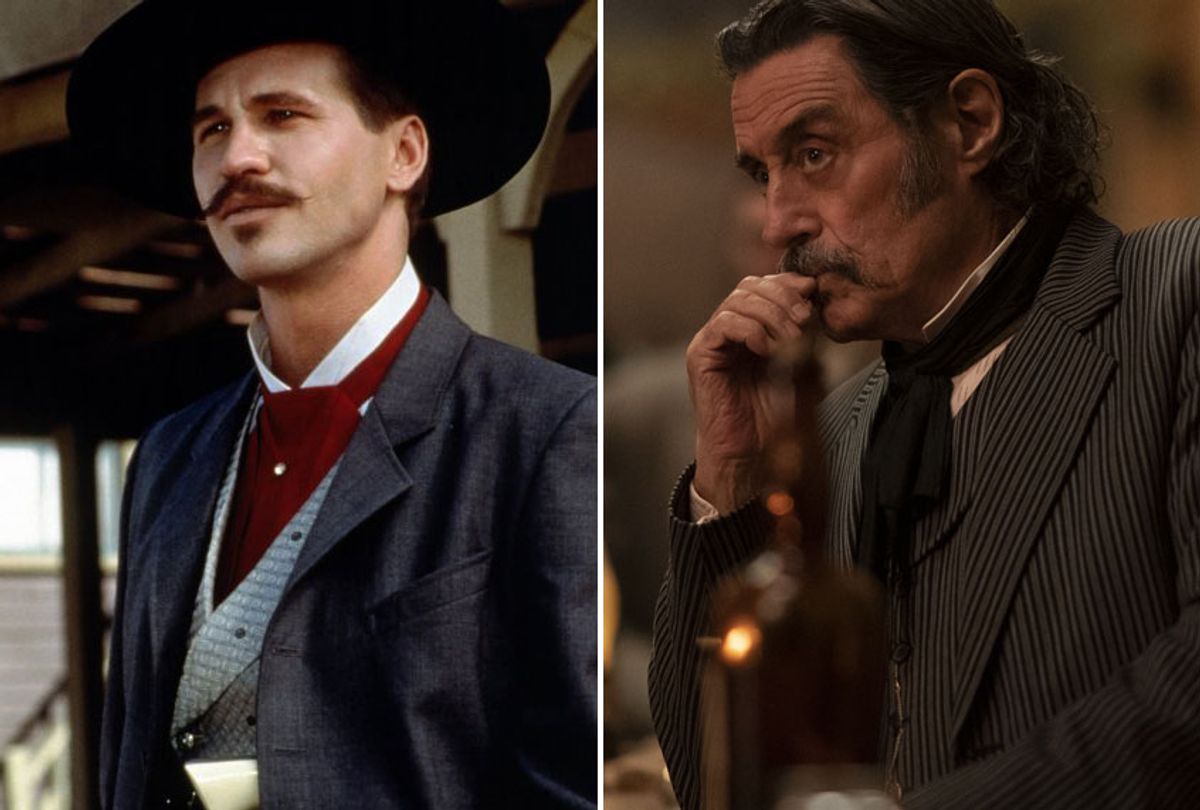

"Deadwood" the HBO series ran from 2004-2006, covering the years 1876-1879, and the railroad never made it there. It’s now 1889 in the long-awaited "Deadwood" movie, and the railroad has arrived, bringing civilization to the South Dakota gold mining town. Some of the inhabitants look even better: Timothy Olyphant, greyish hair slicked back, is splendid as the real life marshal (and, later, friend of Theodore Roosevelt) Seth Bullock. Ian McShane as the real-life saloon/brothel owner Al Swearengen, also in his own way looks splendid, though his own way means looking like a vampire who has been rotting from within for more than a decade.

Most of the principals are back. Robin Weigert as sometime-gunfighter and full time fantasist Calamity Jane; John Hawkes as the town’s entire Jewish population, the merchant Sol Star; Brad Dourif as the aphorism-spouting Doc Cochran; Paula Malcomson as the damaged but durable prostitute Trixie; Kim Dickens as perspicacious lesbian brothel hostess Joanie Stubbs and Molly Parker as the widow Alma Ellsworth, who shows up in town just in time to add to thwart the intentions of Gerald McRaney’s Senator George Hearst (father of William Randolph).

"Deadwood" the TV series owed a debt to Dashiell Hammett’s classic crime novel, "Red Harvest," in which an unnamed protagonist arrives in a western mining town and finds two corrupt factions running a town untethered by law. In Hammett’s novel a maelstrom of violence ensues; in "Deadwood," there’s an uneasy peace on the surface, with boundaries and alliances shifting underneath. Every episode brought some new wild card that threatened to tip the precarious balance of power between Olyphant’s Marshal Bullock and McShane’s Swearengen.

In every episode an atmosphere of dread hung over the town like smog. Most of the iniquities had strong basis in historical fact. Deadwood was a bastard town, illegitimate at birth, settled on land ceded to the Lakota tribes by treaty in 1851. When gold was discovered in the Black Hills in the early 1870s, the government was unable — or unwilling — to stem the flood of prospectors, merchants, saloon owners, gamblers and prostitutes that poured across the U.S. border.

Those caught attempting to cross the line could be arrested and jailed; those who strayed from Deadwood into the hills risked the wrath of hostile Lakota. For three hellish years the atmosphere of greed and corruption attracted many of the frontier’s celebrities — Calamity Jane, Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, and, of course, the Babe Ruth of gunfighters, James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok. (Wild Bill only lasted two weeks, murdered by a vengeful gambler while, according to legend, holding the Dead Man’s Hand: aces and eights.

David Milch, former literature lecturer at Yale and co-creator of "NYPD Blue," headed a team of writers who delved not only into the history of Deadwood but the language as expressed in letters, memoirs, and newspapers. No sooner had someone opened their mouth in the first episode than you knew "Deadwood" wasn’t "Gunsmoke" or "Bonanza."

Critics have debated whether the diction of "Deadwood" is historically accurate, but since we have no audio evidence we’ll never know. But why does it matter? Did Shakespeare replicate the speech patterns of characters in his historical plays?

Milch’s characters speak with the rhythms and patterns of people raised on Shakespeare and the King James Bible, a language short on contractions and spiced with a heavy dose of Yankee impertinence. Here’s an exchange from Deadwood the movie between Bullock and Hearst when the Marshal accuses him of complicity in a murder:

“You're impuding, sir, as a slur meant to incite me. And I do not chose to be provoked. You’re impuding foreknowledge, sir, to me of Mr. Utter’s murder exposes me to slander and disesteem. I will have you recant or either be ready to receive behavior from me to rebuke.”

Bullock replies, “What form then do you figure your rebuke will take, murdering c**t that you are?”

I can’t say if this language is historically correct, but it rocks.

“I’ve never taken any particular pleasure in using what people refer to as ‘dirty words.’ I was always more interested in the language of the period as a whole," Milch told me in a 2006 interview. "I did a lot of research on oral history and the development of language at the Library of Congress, and read H.L. Mencken on American language, too. I’ve always been fascinated by what I call the ‘specialized locutions’ that develop in any environment that was isolated, like Deadwood was, where the people in that environment are dealing only with each other. In those circumstances, a language grows that is rich with expressions you won’t find anywhere else."

Here’s a few more favorites:

A proposition is “easier told than saddled and rode.”

A character philosophizes on the dizzying pace of change in the late 19th century: “We’ve no say as to the pace of modernity’s advance. I myself am merely its vessel, a humble foot soldier …”

Another shrugs in reply, “I am not made for such complexity.”

And everyone, even the children, talks like that. The enjoyment of watching "Deadwood" comes from wondering what the characters will say as much as what they will do.

There is one major problem, though, that the movie must confront. Statehood has come to the Dakotas and gentrification in its wake. There’s no more threat from hostile Indians and gangsters like Swearengen; they can’t just have their enemies’ throats slit and bodies fed to the hogs.

Most of the tensions that held the series story lines together have evaporated. Bullock and Swearengen have settled into an uneasy coexistence, and Deadwood no longer feels like a powder keg near a fireplace. The town’s economy is now based more on lumber instead of gold. Swearengen — God bless him — is suffering from a well-earned cirrhosis and isn’t long for this world. Deadwood needs a new villain to stoke its hellfire, and Milch finds him with the return of McRaney’s George Hearst.

Milch often plays fast and loose with his characters; like any smart creator he’s never been averse to tinkering with the record when it suits his dramatic purposes. The real George Hearst was a hard case and a ruthless businessman, but there is no evidence that he commanded thugs to murder his enemies.

In the movie Hearst is made to represent the coming evils of corporate America, and McRaney, who has never had a better role, is up to the task. And you can see Olyphant growing in the role of Seth Bullock as he confronts him. The movie offers the satisfying showdown and conclusion that the series never had. Thus proving the Nietzschean adage cited in another great western, "Blazing Saddles": “Out of chaos comes order.”

"Deadwood" achieves the difficult feat of being elegiac without the least hint of sentimentality.

"Tombstone," now celebrating its 25th anniversary (though it actually went into limited distribution late in 1993), was in many ways a precursor of "Deadwood." And like "Deadwood," it transcends the genre.

Beginning in 1932 with Walter Huston in "Law and Order," Wyatt Earp and Tombstone have been resurrected in dozens of movies, most notably John Ford’s "My Darling Clementine" (1946) and John Sturges’s "Gunfight at the O.K. Corral" (1957), and television shows, even episodes of "Doctor Who" and "Star Trek." "Tombstone," though, was the first to suggest why the story became legend in the first place.

The silver mining boomtown of Tombstone had uncanny parallels with the gold mining camp of Deadwood. Established at nearly the same time, Tombstone was nearly as isolated as Deadwood, set on a plateau near the Mexican border and perilously close to Apache country. Bands of cattle rustlers and smugglers collectively known as “Cowboys,” protected by local law enforcement, raided Mexican territory with impunity. (Where’s a wall when you need one?)

Kevin Jarre was the first filmmaker to draw inspiration from historical sources and suggest the complexity of the forces that resulted in the clash between the Earp Brothers, Doc Holliday, and the Cowboys. Nearly a decade before Deadwood, Jarre, the adopted son of composer Maurice Jarre, tapped into the rich vein of 19th century American frontier vernacular.

Kurt Russell’s Wyatt Earp tells a sleazy Faro dealer played by Billy Bob Thornton, “No need to go heeled [armed] to get the bulge on a dub like you.”

“Go ahead, skin it. Skin that smoke wagon,” he says, facing the gambler down, “and see what happens. . . . I’m tired of your gas. Now jerk that pistol and go to work.”

To Stephen Lang’s Ike Clanton: “You called down the thunder, well now you’ve got it. You tell ‘em I’m comin’, and hell’s comin’ with me!”

Val Kilmer’s Doc Holliday, though, gets the best lines, which he delivers in an impeccable aristocratic antebellum accent. To an enemy who tells him he’s so drunk he’s seeing double: “I have two guns, one for each of ‘ya.”

Wyatt tries to coax a drunken Doc to go home and sleep it off, and Doc replies, “Nonsense. I have not yet begun to defile myself.”

A tinhorn gambler, pissed at losing a hand, calls the tubercular Doc “a skinny lunger.” Kilmer deadpans with a drawl, “What an ugly thing to say. I abhor ugliness. Does this mean we’re not friends any more?”

When Michael Behan’s Johnny Ringo tries to provoke an unarmed Wyatt, Doc picks up the challenge: “I’m your huckleberry — that’s just my game.” The NBA’s Karl Malone helped popularize the phrase, taunting opponents before a jump-ball “I’m your huckleberry!” And “I’m your huckleberry” even made its way into a "Key & Peele" sketch.

Perhaps Doc’s most famous phrase came during the gunfight when a Cowboy, holding a gun on him at point blank range, says “I’ve got you now, you son of a bitch!” Doc, who has no fear of dying in a gunfight, faces him with a smile and open arms: “You’re a daisy if you do.” (According to western historian Jeff Morey, Jarre’s consultant on the film, a newspaper reported that Holliday actually said this.)

Jarre, who died in 2011 at age 56, was a terrific writer; he also scripted the greatest of all Civil War movies, "Glory" (and gave himself a cameo in the film as a Union soldier who clashes with Denzel Washington).

It’s a shame that he couldn’t direct as well as he wrote. With the filming of "Tombstone" moving at a snail’s pace, the producers fired Jarre and replaced him with Rambo-hack George Cosmatos. The result is a sometimes disjointed plot in which some key points are unexplained. But for the feel and look — the costumes, hair, hats, mustaches, guns, and the interiors of saloons and the famous Bird Cage theater — and for Russell and Kilmer, the best Earp and Holliday ever, "Tombstone" is exhilarating. And given Hollywood’s waning interest in our frontier history, perhaps the last great western.

*** Allen Barra is the author of Inventing Wyatt Earp: His Life and Many Legends.

Shares