Over the first weekend of June — a month that brings us the beginning of summer and the official beginning of the Democratic presidential campaign — Sen. Elizabeth Warren had a series of news moments pointing in conflicting directions. They serve to illustrate the uncertain character of Warren’s campaign, which appears finely balanced between breakthrough and collapse, and also the uncertain state of her party.

On Friday, Warren appeared on “The Breakfast Club,” a syndicated radio program whose hip-hop-oriented national audience, largely but not exclusively younger people of color, has made it an important platform for Democratic candidates. Generally speaking, it was a friendly encounter — from this white observer’s perspective, Warren appears to have impressed black audiences with her frank and specific talk about the pernicious economic and social effects of racism. But along the way co-host Charlamagne tha God called Warren “the original Rachel Dolezal,” comparing Warren’s previous claims of Native American ancestry to the white woman who infamously presented herself as black for many years.

Warren’s supporters can respond that the comparison is deeply unfair, and they’re probably right. There’s no clear evidence that Warren gained any tangible advantage from having occasionally described herself as “American Indian,” and that identification was at least based on plausible and consistent family legend. Her DNA test revealed at least some Native ancestry several generations in the past, although the same could be said of a great many white people whose forebears came to North America in the 19th century or earlier. (My own family genealogy lore includes a presumed Native American great-great-grandmother; I have no idea whether that’s true.)

But the awkward Dolezal moment went viral, and the accusation stings for a wide range of reasons. It feeds into Trump’s profoundly offensive “Pocahontas” insults, and right-wing media gobbled it up and recirculated it accordingly. It interlocks with genuine issues of white privilege and a widespread, not entirely untrue perception that “identity politics” can be manipulated for cynical purposes. It also conjures up the specter that haunts the 2020 campaign, whom Warren at least superficially resembles: Hillary Clinton.

Of course these two women are not much alike in terms of personality or ideology, and their class backgrounds could hardly be more different. The resemblance is almost entirely a matter of insidious sexist stereotype — the pantsuit-clad female policy wonk who has “a plan for that” — but it does no good to pretend it isn’t there or doesn’t matter. Everyone in the 2020 race, male or female, is doing battle with Hillary’s ghost: They must simultaneously appeal to Clinton’s supporters, who still passionately wish for an America where she was president, and also to those who see her as the shifty, untrustworthy embodiment of the Democratic Party’s rootlessness, neoliberal triangulation and internal corruption.

After the exceedingly uncomfortable Charlamagne exchange, which pointed to a weakness that is only partly Warren’s fault, she proceeded to show her greatest strengths. That same evening she drew an enormous crowd to an outdoor rally in Oakland, California — hometown of one of her presidential primary rivals, Sen. Kamala Harris — and the next day went across the bay to deliver a fire-breathing speech at the California Democratic convention, by many accounts the biggest hit of the entire event. (Harris, Bernie Sanders and Beto O’Rourke were also well received.)

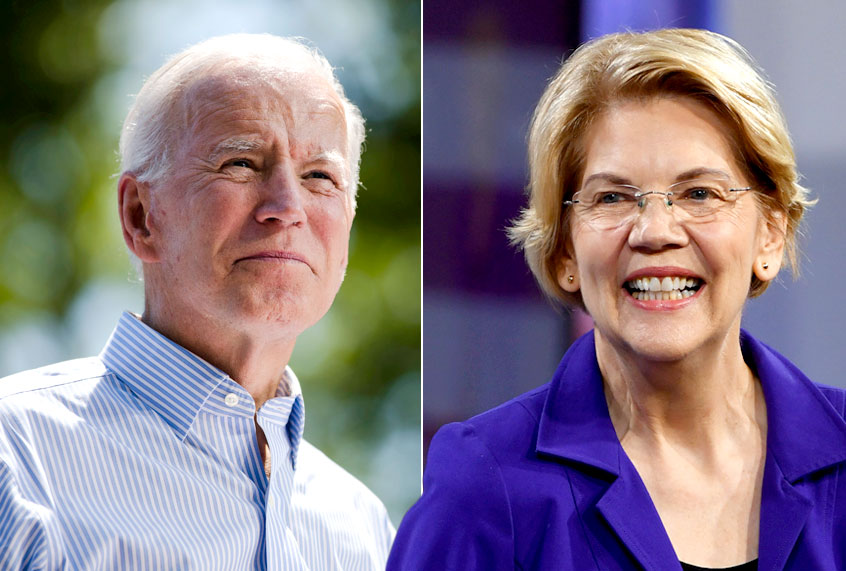

“For decades, the entire structure of our system has favored the rich and the powerful,” Warren told the delegates in San Francisco, tying her dense list of policy proposals to a systemic critique and a mission to reclaim and repurpose the Democratic Party. She took a none-too-subtle shot at former Vice President Joe Biden’s claims that Republicans will have an “epiphany” once President Trump is removed from office, and that a Biden presidency will restore us to a mythical era of amicable bipartisan compromise. “Some say if we all just calm down, the Republicans will come to their senses,” Warren acridly proclaimed. “But our country is in a time of crisis. The time for small ideas is over.”

Let’s make the ritual pronouncement that it’s way too early for horse-race punditry, which is not all that useful at the best of times. Who’s going to win? Who should win? I have no idea. Bill Moyers told me years ago that those were always the least interesting questions in politics. The important questions are about why things are happening the way they are, and what stories we tell ourselves to explain them.

Win or lose, Warren is a highly significant figure in the Democratic Party’s 2020 quest for relevance, which goes far beyond the urgent question of defeating Trump. In practical terms, she is running the most idea-rich, policy-driven presidential campaign in recent memory, and as she made clear in San Francisco, is proposing not just standard-issue liberal-bureaucratic tweakage but large-scale economic, social and juridical reforms. Her approach to feminism and “women’s issues,” in this male viewer’s eyes, has felt both natural and skillful: She is unafraid to “lean in” to her identity, especially when addressing girls and women, but always as part of a larger agenda of national reform and redemption.

In symbolic terms, Warren represents the possibility of healing the Bernie-Hillary split that so bitterly divided the Democratic coalition in 2016, and continues to linger in the air like burnt roast in an apartment kitchen. She is almost literally a fusion of the two, an educated and ambitious woman who is strong on the details, but who also perceives the scale of America’s crisis and demands big-picture structural change. If anything about the overcrowded Democratic field makes sense (which is debatable), then Warren makes hypothetical sense as the most viable alternative to Joe Biden. She can now just barely glimpse a narrow pathway to that goal.

Just a few weeks ago, mainstream commentators had largely given Warren up for dead amid Pete Buttigieg’s surge and the Biden bounce and the launch announcements from (apparently) every white male Democratic office-holder in the Mountain West. But her admirers kept the candles burning in the social-media darkness — how many plaintive tweets have you seen extolling her ever-lengthening list of policy proposals? — and Warren herself kept cheerfully trudging from one town meeting to another, often in the Trumpiest, most Nowheresville places imaginable.

It’s working, at least in the sense that her crowds have consistently gotten bigger and the media has discovered her all over again. Maybe she wasn’t “likable” in the winter months, but she’s plenty likable now! Warren was the first prominent 2020 candidate to call for Trump’s impeachment following the release of the Mueller report — most of the others have now followed along — and effectively stands alone in her refusal to hold a town hall meeting on Fox News. “I’ve got a plan for that” has become a meme, and mostly in a good way.

Polls of likely Democratic primary voters have been largely stagnant since Biden entered the race — and should not be taken too seriously at this stage — but Warren has crawled back into third place, a point at a time. OK, she’s a distant third, closer to ninth place than to first. But that’s unmistakably better than tumbling into the bottomless Gillibrand-Hickenlooper vortex south of 1 percent, from which physicists tell us no light or matter or energy can escape. If old-school political wisdom held that there were only three tickets out of the Iowa caucuses, this time around there might be only six tickets that get you there in the first place.

Warren’s path to being the last person standing between “Sleepy Joe” and the Democratic nomination — perhaps you haven’t noticed this, but Trump possesses a playground bully’s keen instinct for insulting nicknames — relies on a long list of ifs and maybes. (But then, so does everyone else’s.) If Sanders has been too badly damaged by 2016 and cannot expand beyond his core support of 20 percent or so; if Harris is already effectively running to become Biden’s running mate; if Buttigieg and O’Rourke have had their exciting gap-year adventures and can head back to real life now; if everyone below Cory Booker and Amy Klobuchar is already irrelevant but sticking around as an obscure “career-building” exercise.

All those things are individually plausible, even likely. But for Elizabeth Warren to avoid being remembered as a latter-day Adlai Stevenson or Eugene McCarthy — the thinking person’s candidate who couldn’t seal the deal — they all have to be true in the right sequence and at the right time. (Followers of British politics might identify an even better cognate in early-’80s Labour Party leader Michael Foot.)

Although the Democratic campaign will be long and arduous, the actual 2020 primary calendar will be exceedingly short, a fact the strategists and consultants have grasped but the public likely hasn’t. The Iowa caucuses are on Feb. 3, with the New Hampshire primary eight days later. Three weeks after that comes the first Super Tuesday on March 3, which for the first time will feature California, the biggest delegate prize of all, along with 12 other states, including Colorado, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Texas and Virginia. It’s unlikely that more than two candidates will be left standing at that point; Joe Biden’s campaign fully expects there will only be one.

In some ways, it’s a more deeply skewed or “rigged” system (if less intentionally so) than the one that drove Sanders supporters bananas four years ago. As Elizabeth Warren and the rest of the un-Biden candidates are well aware, the battle for hearts and minds can’t wait for that disorienting month of political blitzkrieg. It must happen now, and it’s a psychological battle as much as anything else.

For Warren or anyone else to prevent the uniquely depressing experience of a Biden “national unity” campaign, specifically targeted at a tiny cadre of wobbly Trump voters and Jeff Flake-style dissident Republicans, something has to change before next winter. Democratic voters and the media and basically everyone else must get over their skittish, fearful response to the Trump presidency, and their based-on-nothing certainty that nominating a progressive or a woman or a socialist or anybody who isn’t an avuncular white man with a vaguely reassuring demeanor and no discernible ideology will once again lead to disaster. They have to get past the trauma of 2016, face the ghost of Hillary Clinton and put it behind them, and move on. It may be too much to ask, but at least Warren has a plan.