In May 2019, the Jackson County Detention Center In Kansas City, Missouri, with no warning to local attorneys, instituted a new security policy that requires all visitors, including inmates’ attorneys, to pass through a metal detector. That seems reasonable in theory, but the practice has led to what one assumes is an unintended side effect: Some women’s underwire bras are setting it off. In response, instead of simply using a wand to determine what is setting off the alarm as other prisons do, the center is refusing to let visiting women pass through until they do not set off the detector. Which means, in practice, that their bras must come off.

This is not unique to Kansas City. An even more draconian policy was implemented in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in 2018: Visitors were given only two chances to pass the metal detector — and women were required to wear a bra under prison rules. These policies resulted in women removing the wire from their bras or buying new ones. A Maryland jail was sued in 2011 after two women were required to take their underwire bras off before visiting, even though prison officials had stated four months earlier that underwire bras were allowed. Indeed, there is a long history of prison rules that uniquely disadvantage women, whether as inmates or visitors.

What makes the situation worse in Kansas City is that this is a detention center, not a prison; almost everyone held there has not been convicted of a crime and is therefore presumed innocent. Moreover, it is attorneys — who have already been vetted by the detention center — who are being turned away. A similar situation in Portland, Maine, in 2015 led to official apologies. But in Kansas City, the officials’ response to the attorneys’ complaints has actually added insult to injury.

First, Jackson County Sheriff Darryl Forté denied that the problem was even happening, calling it “misinformation” and insisting that no one was told to take their bras off. This is technically true. But as one attorney put it, if the choice is entering the detention center sans bra or not seeing your client, the detention center isn’t actually giving you a choice. Similarly, when the issue was brought to the attention of a judge as part of a larger proceeding about the burdens suffered by the public defenders in Jackson County, the (male) judge also denied that the problem existed, arguing that no one else seemed to have a problem with it. These denials of the actual experiences of female attorneys are extremely troubling.

Next, the director of the Department of Corrections, Diana Turner, offered a “solution”: Women could keep their underwire on but would only have “no contact” meetings with inmates, means that attorneys would have to confer with their clients through glass. As the attorneys have pointed out, this “solution” impedes their ability to meaningfully interact with their clients and build a rapport with them. Using a telephone to communicate through a pane of glass makes it impossible for attorneys to go over evidence with their clients or have them sign documents, which are essential tasks for a lawyer, particularly when their client is still awaiting trial. It’s no wonder that the attorneys found this solution to be a non-starter.

Turner also attempted to turn the gender issue into a class issue by accusing the complaining attorneys of “want[ing] privilege” as part of the “educated elite,” pointing out that all corrections officers must pass though the same security. Turner argued that attorneys have essentially stated that “it’s reasonable to suspect your people. Your staff is just [corrections officers].” No complaining attorney, however, has ever stated that female corrections officers should be subjected to this policy. Moreover, there may be a valid reason to treat corrections officers differently. There is no record of an attorney ever smuggling contraband into the facility, but just last year a former Jackson County corrections officer was sentenced to 16 months in federal prison for smuggling contraband. Finally, the detention center strip-searches every inmate after they meet with their attorneys. So even if attorneys were trying to smuggle in contraband, corrections officers would catch it in the normal course of events. So this isn’t about contraband at all. Something else is going on here.

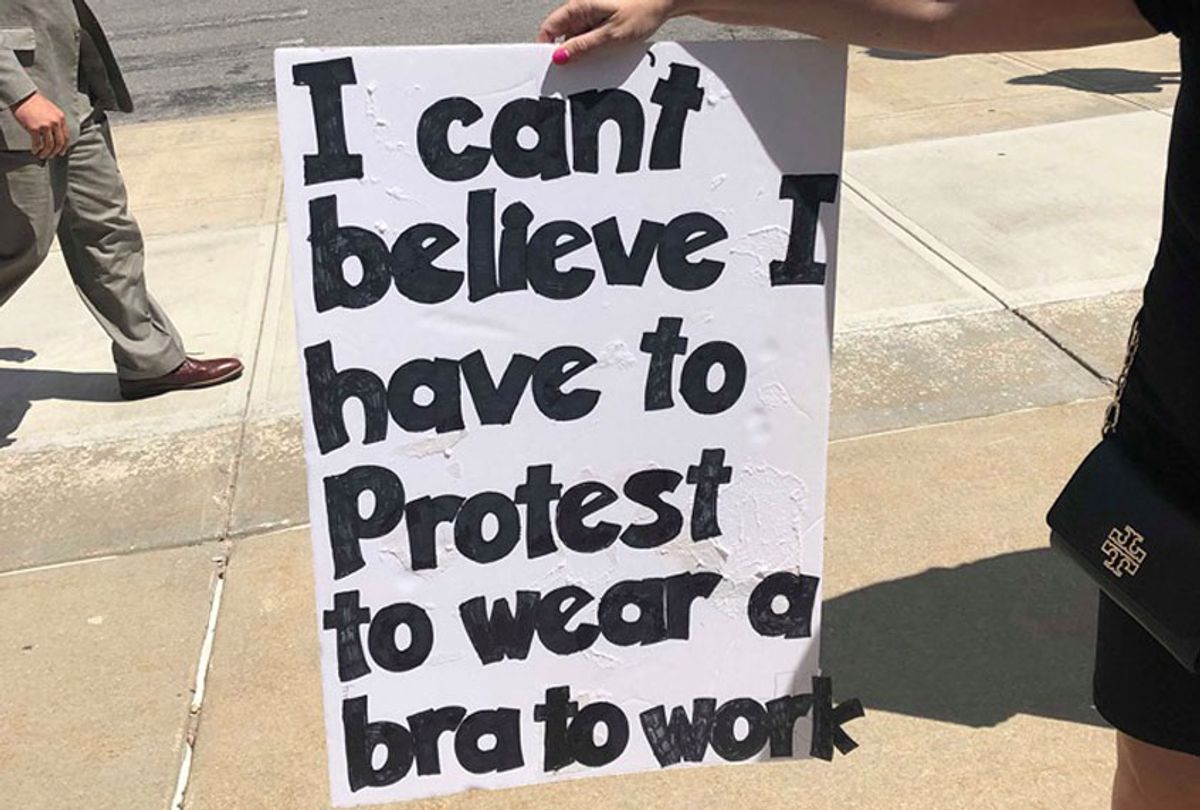

Back to the story. Despite Forté and Turner’s best efforts, this issue has not gone away. A letter was signed by more than 70 attorneys — men and women — and addressed to prison officials as well as the local legislature. The issue was publicly taken up by county legislator Crystal Williams, and last week there was a peaceful protest outside a 90-minute meeting of the county legislature. At that meeting, however, the attorneys were met with intransigence. Sheriff Forté said the county would not change its policy, despite several legislators voicing their concerns. Forté agreed to meet with the complaining attorneys, but no date has been set and there is no reason to be hopeful he will have a change of heart.

Indeed, the sheriff has already retaliated. Forté recently filed a Sunshine Act request to see the emails from attorneys to legislator Williams regarding this issue. When criticized, Forté defended his request as an effort to “educate the community about open records, as well as to ascertain facts about alleged comments.” It is unclear what “education” his request will provide or what “facts” he needs to discover.

So, for those keeping score, when women (and, later, men) complained about a policy they found unnecessary, humiliating and sexist, they were met with gaslighting, false solutions, accusations of privilege, stonewalling and, finally, retaliation. And this was against attorneys, who by definition are well positioned to fight back. There are 300 female workers at the Jackson County prison and several of them had to buy new underwear just to do their jobs, which Turner described positively as “making adjustments” to the policy. The workers’ union complaints make clear, however, that they would have preferred to avoid this unnecessary expense and merely capitulated to keep their jobs.

And the chaos continues. A week after the legislative hearing, attorneys reported that their underwire bras were no longer setting off the metal detectors, though Sheriff Forté has stated that the machines were not changed. After those first reports, however, the metal detectors were no longer going off, they began to go off again, leaving attorneys wondering whether BraGate 2019 will ever be resolved.

Shares