When Joe Biden unveiled his health care plan there were the usual echoes of Hillary Clinton. She used to do a bit in which she’d tremble at the “chaos” that would erupt if we even spoke of single-payer. Biden told the AARP that under Bernie Sanders' plan there would be a “hiatus” in which seniors might lose coverage (followed by locusts, frogs and the Angel of Death). Sanders punched back; thus we got the lovely New York Times story, "Biden and Sanders Fight over Health Care, and it’s Personal."

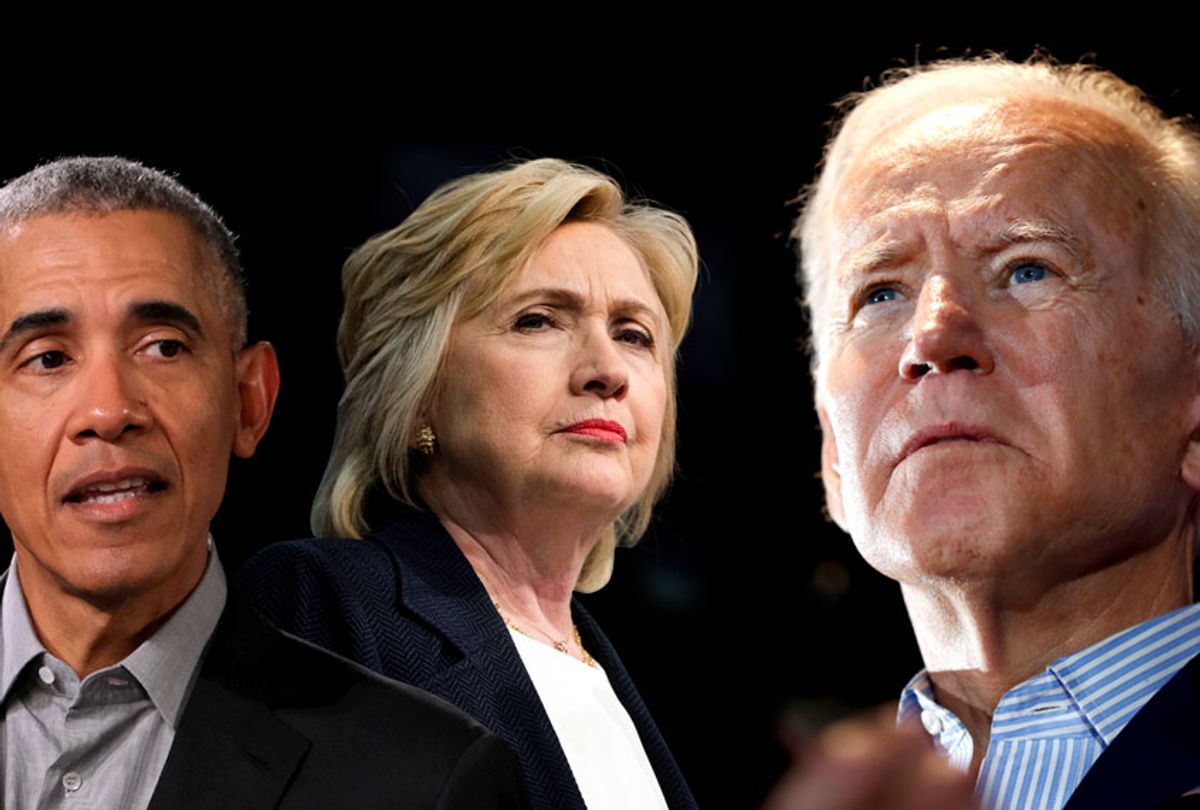

Biden is now the full-time keeper of the Obama flame. Democrats have affection for Obama, but also a rising sense that his reluctance to challenge the political and economic establishment was a big part of what got us into this mess. Biden’s plan is actually slightly bolder than he makes it sound; linking it to the barely popular Obamacare only lessens its appeal to progressives and swing voters alike.

Biden says his plan will cover 97% of all Americans and cut costs for the currently insured, and will cost $750 billion over 10 years, paid for by raising earned-income and capital-gains tax rates on the rich to 39.6%. Its centerpiece is a public option more or less like the one Obama abandoned in early 2009. I say "more or less" because we never saw the details of the first model and still haven’t seen details of this one.

Biden presents his plan as an alternative to a single-payer system, rather than a way station on the road to one. He says not a word about what happens once it’s up and running, leaving us to assume he imagines the majority of non-elderly adults will be covered indefinitely by for-profit insurers through their employers.

In the current atmosphere, the Public Option vs. Medicare for All debate is unlikely to advance much further. It’s too bad. Speaking as one inclined toward Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, I believe enactment of a well-designed public option is the fastest, maybe even only, road to affordable, universal health care.

The charge that single-payer health care costs more than our present system is a lie easily exposed by, well, all the data in the world. The charge that the transition to such a system is costly and disruptive is true. It’s also true that millions of people become anxious when told they may be forced to give up their current coverage for a system we haven’t built yet.

Build it and they will come. If everything progressives believe about health care is true, the instant a real public option is available, they’ll be busting down the doors to get in. Insurers fear it more than they fear single-payer because they know it’s more easily achieved, and because they know where it will likely lead.

In 1991, as Connecticut’s new state comptroller, I proposed what I believe was the first health care public option in America; for sure the first to pass a legislative chamber. Three decades later, Connecticut is still the only state in which the idea has made it even that far. Such is the power of the insurance industry.

My idea was simple: Fold all municipalities into the state employee plan. Open that plan to small businesses and the self-employed. With new enrollees paying full price there’d be no cost to taxpayers; in fact, the state’s costs would fall as per capita overhead dropped and a bigger pool negotiated lower provider prices.

The big winners were small businesses. Insurers said they paid more for health insurance because their employees got sicker than people who work for big business. That’s not true, of course. Small businesses pay more for health care for the same reason people in central cities pay more for groceries; they lack the clout to cut a better deal. I estimated at the time that by joining the state plan, a small business could lower its premiums by 25%. A later study put the nationwide figure at 18%.

We lost that fight, but the idea spread. In 2008 Barack Obama ran for president on two big promises: to curb corruption and achieve near-universal health care via a federal public option (with no mandate). His anti-corruption agenda famously included letting C-Span cameras in the room to cover health care negotiations.

In office, Obama met secretly with health insurers — no cameras allowed — and switched sides: There would be a mandate after all, but no public option! Prices would fall only for those eligible for subsidies. For everyone else, prices kept rising, only now they had to buy the very same private insurance Obama had said they couldn’t afford, or pay a fine. A 50-year-old earning $46,000 a year who still couldn’t afford health insurance now paid a 2% income tax surcharge to boot. Hurray.

It was arguably the biggest mistake of Obama’s presidency. The Congressional Budget Office and his own Office of Management and Budget would later find that the public option was the key to cutting government health care costs, but Obama had cut his deal and thus sentenced himself to endless budget and health care wars.

Some people trace the fight for universal health care back to Teddy Roosevelt’s 1912 Bull Moose platform. Progressives endorsed it then, but no one fought hard for it till much more recently; specifically, until just before Bill Clinton became president. That’s because until 1980 or so, health care in America didn’t cost that much.

In 1960, annual U.S. health care spending added up to a grand total of $146 per person; $1,263 in current dollars. By 1980 it had risen to $1,180 per capita, or $3,368 today. In 2019, per capita health care spending in America tops $11,000 a year.

If you ask an insurance lobbyist what drives health care inflation, he’ll start with hypochondriacs and trial lawyers, move on to the aging population and advances in science and end by throwing doctors under the bus.

The idea that Americans are recreational consumers of medical care, other than drugs, is a myth; if we saw doctors earlier and more often, we’d spend less on health care, not more. The accountability trial lawyers impose on the system actually lowers costs. Demographics, science and overpriced specialists are real issues. But the biggest problem is one the lobbyist leaves out: his own industry.

According to a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, 30 cents of every health care dollar spent in America goes to overhead. In Europe, the figure is closer to a dime; in Asia even less. Twenty cents of every dollar go to physician services; that’s 50% more for paperwork than for doctors’ care.

The prize for second-highest overhead goes to our neighbor to the north, Canada, which spends about 16 cents of every dollar on it. Fun fact: If we could just tie Canada for last place in that category instead of having it all to ourselves, we’d generate enough savings to cover every single American left behind by Obamacare.

Progressives often say that every other major Western nation has single-payer health insurance (i.e., government pays the bills but most doctors and hospitals are independent). In truth, only a half dozen or so do. Three or four others have national health services like the U.K.’s, where everybody works for the government. All the rest have insurance companies. Some, like France, have a single insurer or "trust." Others, like Germany, have many. What all these countries have in common is that their principal insurers are nonprofits.

It was once that way here. Nonprofit Blue Cross Blue Shield had most of the nation’s business until the 1980s, when it began converting to for-profit corporations. Property and casualty insurers soon jumped into the business. By the late '90s, nonprofit health insurance in America was almost extinct. For decades, the for-profits vowed to contain costs. Not only did they fail, but the costs that rose the fastest were their own — the endless paperwork that never cured so much as a hangnail.

The second-fastest rising health care cost after overhead is drugs. The timeline is nearly identical. In 1960, Americans paid less than $100 per capita for all drugs. Until 1980 prices hardly budged. Then they began rising at double to triple the rate of inflation. On average, Americans today spend $1,500 a year for prescription and over-the-counter drugs. In Britain the comparable figure is $469. Drugs account for 13% of all U.S. health care spending

Obama made the same pact with Big Pharma he made with the insurers: Hold the industry harmless, allow no Medicare price negotiations and no Canadian imports. His bill was called the Affordable Care Act, but before the fight even began, 43% of all health care spending was shielded from any threat of effective cost containment.

Our system inflates costs in other ways. One is the aforementioned price gouging of small business. Another is fraud perpetrated by hospitals, doctors and labs; that is estimated at 6% or more of all health care spending in the U.S., versus roughly 3% in Europe, due partly to the patchwork nature of the American system. But the worst culprits by far are the insurance and pharmaceutical industries.

The great rise in health care costs in America began in 1980 with the advent of the Age of Reagan. It has been largely driven by two industries whose greatest skill is rigging the political system to extract excess profits from a business that literally means life or death to its customers.

Last week, Sanders challenged other candidates to refuse donation from the insurance and pharmaceutical industries. Biden, Kamala Harris, Pete Buttigieg and others are still on the take. If they were taking from the NRA, their campaigns would be over. Do we really think drug money comes with fewer strings attached? Cutting those strings is the first step on the road to real change.

One reason Obama made such bad deals is that he didn’t fully understand them. He’s a big-picture guy, less interested than a Bill Clinton or Al Gore in how things actually work. He paid a price for it in health care, as in the disastrous Obamacare web portal and endless VA scandals. Obamacare brought massive change — but the move to universal health care is more massive still. It’s fair to ask proponents to get the system up and running before compelling everyone to sign up.

Bernie calls his proposal Medicare for All. In practice, provider networks, benefit design and financing would all be different from Medicare. I’m not sure Bernie’s any more of a detail guy than Obama. I don’t know if a Canadian or French system is a better fit here, or which I prefer, or whether I care.

Biden was part of the team that promised but never delivered a public option in 2008. He hasn’t promised to end the for-profit insurance industry that transformed an affordable health care system into one that bankrupts families, businesses and governments. The industry still funnels him money. He has questions to answer.

You know the litany: The U.S. spends twice as much per capita on health care as the other 35 developed nations, but ranks 28th in life expectancy, 33rd in infant mortality, etc. A system that leaves 50 million uninsured for a part of every year isn’t the only reason, but it’s the biggest one. If Democrats win the White House and Senate in 2020, they’ll get their second chance in just over a decade to fix it. If they blow it, there’s no reason to think they’ll ever get a third.

Not blowing it means making the system cost-effective. Universal health care costs far less than the system we have. Bernie Sanders is at his least compelling trying to explain why his plan will cost $14 trillion rather than $35 trillion, and how its low premiums, deductibles and copays will make it less costly in the end. It’s all true, but it's hard to explain. One signal virtue of a transitional public option is that it requires less explanation.

Not blowing it means creating a system that works better than the Obamacare web portal. Another virtue of the public option is that it gives the White House and Congress and every stakeholder the time they’ll need to build it right; to slash overhead and prescription drug prices, end small business price gouging and root out corruption.

A well-designed public option would save money on day one. The individual market — 9% of the population — would flood into it. Big employers would clamor to be next. For-profit insurance would collapse because it simply could not compete.

Sanders' bill has 20 Senate co-sponsors, but that includes people like Harris and Cory Booker who are clearly just kidding. Even if a Democratic Senate abolished or circumvented the filibuster that bill would need 50 votes to pass, which renders the current debate nearly moot. An even greater risk is that we run on single-payer, fail to weather all the attacks on it, and lose.

Biden says his bill would cover 97% of the population, but there’s no reason to stop there. His cozy donor relations and failure to specify a pathway to universal health care make me suspect he isn’t the man to lead us there. But progressives should think long and hard about our strategy for getting there. It’s our last chance too.

Shares