"Don’t confuse me with the facts," my brother Steve used to joke if I questioned the accuracy of something he said.

Here's a fact: he was my much older half brother from my mother's first marriage. Here's another: until the summer after my freshman year of high school, I thought he and our sister Tina were my distant cousins. Before then, as far as I knew, I had one sibling, my sister Andra who had been adopted into our family six years before I was born.

Have I done it — confused you with the facts? It's no wonder. Long before Counselor to the President Kellyanne Conway blithely introduced the phrase alternative facts into our country's lexicon, my parents chose to raise Andra and me in an alternative facts home.

My parents were in their 40s when I, their surprise late-in-life baby, was born, but this was yet another fact I didn't know for the first 14 and a half years of my life. Our parents told Andra and me, as well as neighbors and friends, that they were 10 years younger than they actually were. They either told us or implied by omission that neither of them had been married before. As for our mother's other children, they were easy enough to hide. Steve and Tina lived 3,000 miles away from our house in Queens, New York. By the time I was born, Tina, at 17, would have been poring through college catalogs. Steve, at 20, had just asked his beautiful pregnant girlfriend to marry him.

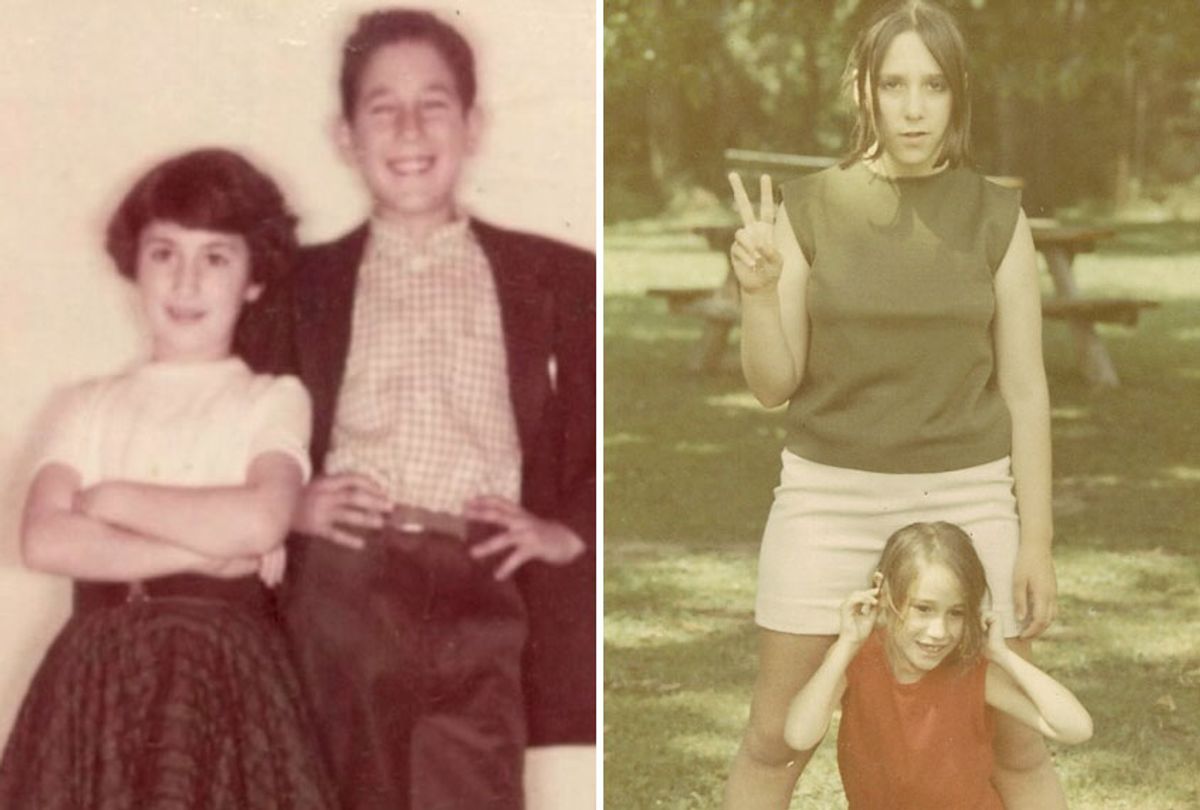

While Andra remembered those alt-cousins of ours from a visit out west during my infancy, for most of my childhood the one place Steve and Tina existed for me was in a fat envelope of black and white photos my mother kept on a high shelf of her bathroom closet. While she cleaned, I'd ask her to take them down for me to browse through. What fascinated me was that the girl who rode bikes or opened holiday presents with her brother, and posed in the swing skirts and bobby socks of another era, looked remarkably like me.

"So who's their dad?" I asked one afternoon.

"His name is Gene," my mom answered as she wiped around the sink.

"And he's your cousin?"

"Right." She sprayed the mirror.

"Who's their mother?"

Here she paused to stare at me through the misted glass. "We don't talk about her."

"Why? Was she a bad person?"

"No! Not at all."

Was she a bad person? Was my dad? My half siblings were seven and four when their father and my mother divorced in 1950. Steve was allowed to choose which parent to live with and picked Gene. Before my parents married three years later, they put Tina on a plane to Nevada where her father and brother had already settled. They told her it was just for a short visit. As far as I know, this was the first of their alternative facts. They'd only bought Tina a one-way ticket. She learned over the phone she wouldn't be coming home.

It may have been during that same call that both she and Steve were given their first instruction on how they were to live in this new post-truth phase of their lives. They were no longer allowed to call our mother Mom.

I've tried to place myself in the small body of one of my siblings during that conversation, to feel the phone grow warm against my ear, to hear my mom's familiar voice as she announces this new incomprehensible rule. But I can't stay there. Instead, lines from a Sharon Olds' poem float through my mind.

…they are about to get married, /they are kids, they are dumb, all they know is they are /innocent, they would never hurt anybody. /I want to go up to them and say Stop, / don't do it… / you are going to do things /you cannot imagine you would ever do, /you are going to do bad things to children…

But in fact my parents were neither young nor innocent. They married in their 30s. My father had fought in the war. My mother was, well … a mother, one who agreed to sever her relationship to her children because her new husband had no interest in being a step-parent. Nor did he want anyone in their new community to know he'd married a divorcée.

What he did want were his own children. Early in their marriage, he and my mom had a baby boy they named Peter. They also had a blood incompatibility that caused Peter to die after only three days. At least two miscarriages followed, after which my parents decided to adopt Andra. More accurately, my father made that decision. Unable to have more than a surreptitious, acquaintance-level relationship with her own kids, my mother begrudgingly took on the responsibilities of caring for the six-month-old stranger who would become my big sister. Not that she ever described her feelings to me in this way. She didn't need to. Long before I learned of her other family, I witnessed how harshly she punished Andra for the smallest infractions. I saw how she regarded my sister and seethed.

They did bad things to children. Abandonment, erasure, gaslighting, and, in Andra's case, abuse. All of us affected. All of us somehow marked. It's there in Steve's five marriages, in Tina's perseverating about the past, in Andra's addictions, and my guilt and self-doubt. It may also be in the fact that, of the four of us, I — the only child they consistently loved and cared for — am also the only one still alive to tell the tale. Or rather, to examine what my parents' telling of tales did to us and to try to make sense of our truth.

Andra started running away at 12 years old. From that point on, her time at home was sporadic at best. She spent much of her teens in reform school, foster care, and in places unknown to any of us. Before she turned 18, she was out on her own. Often, we had to wait to hear from her to learn her whereabouts since she rarely had access to a working phone.

Eventually, Andra landed out west, sought out Tina, and stumbled upon our family secret. If we don't tell Ona, she will, our parents figured. So, in the summer of 1977, my mom flew with me to San Francisco, ostensibly for Andra's 21st birthday. Soon after we arrived, she sat me down in our hotel room with my sister, and the woman, my doppelganger, I believed to be my second cousin.

"I have something important to tell you," she began.

"When parents lie to their children they are hurting them deeply," psychologist Kate Roberts begins a 2014 article in Psychology Today.

I could practically see my sister Andra roll her eyes as I read this. No shit, Sherlock, she'd say. Still, I read on. "When parents tell a child that what they know to be true, in fact is not, they cause the child to choose between trusting themselves and trusting their parents. This is not a choice a child can make and remain intact and healthy."

I was born in the '60s, a decade that would come to be defined by revolution, free love, and letting it all hang out. But my birth year, 1962, was really the tail end of the sanctimonious '50s, a time when, as my father would eventually say to me, no one but Elizabeth Taylor got divorced.

My parents were both first generation Jewish Americans whose own parents had narrowly escaped the pogroms of Eastern Europe. Assimilation, they were taught, was necessary for survival. It must have seemed that the only way to blend into the carefully curated world of post World War II America was to smooth out their surfaces, to hide the messiness of life away.

They weren't alone in this. Around the corner from the house I grew up in, a boy we knew was raised by grandparents he thought were his parents. Another friend's older sister appeared as a flower girl in their parents' wedding album and no one in their family was permitted to ask how that could be. By the time I'd arrived, red faced and squalling, to join my fearful, secretive family, the mythology my parents had decided on was already 10 years old.

I'm writing this in 2019. My immediate family is long gone. I lost Tina, my parents, and Steve to illnesses. But first I lost Andra — the sister I started out with, spoke my earliest words to, touched tongue to tongue so we'd share a secret of our own — to violence. In the absence of my kin, I've managed to uncover more, even darker family secrets. I've also had to navigate this new version of our country where facts simply don't matter. Where, as the current administration continues to have its way, we've begun to lose any sense of a shared reality, of an objective truth.

"Truth," as historian and essayist Rebecca Solnit has written, "is whatever the powerful want it to be."

Arguably, my parents prepared me well for this. "Ah, here we go again," I might say with a shrug of recognition each time the president tells one of his, on average, 12.2 false claims per day (according to the Washington Post's Fact Checker). Or whenever one of his many enablers backs him up, lies on his behalf, or simply looks the other way. It is indeed familiar, and the prevailing feeling — one of disorientation and dismay — is one I know in my core. But believe me, there's no shrug.

Secrets and lies, of course, helped put Donald Trump in office. Secret help from Russia, lies in the form of fake news, districting designed to cheat. Now that he's there, he holds onto his power by working to erode our trust in scientists, journalists, each other, and ourselves.

"When parents tell a child that what they know to be true, in fact is not, they cause the child to choose between trusting themselves and trusting their parents."

"And just remember," Trump said in a speech last year, "what you're seeing and what you're reading is not what's happening."

"Edie didn't have a mean bone in her body," Steve once said to me about our mother. We were both adults by then, the sole survivors of our fractured family, though Steve had already fought and narrowly won several battles with the disease that would eventually claim his life.

"How can you think that?" I'd asked, astonished to hear this from the first of my mother's children she'd abandoned and denied. But somehow Steve and our mom had developed a tender connection in her final years, one that allowed him to put the old hurts behind him. As I went on about the selfishness of her choices and the wounds they'd caused, he listened patiently but didn't waver. Not one mean bone.

It now seems to me that he was speaking back through time, reaching out to me as a five- or six-year-old as I tried to make sense of a story I was only given in bits. Who was this woman we didn't talk about, I had wondered as I held a snapshot of her children in my small hand. Why was she off-limits? With no sense of the complexities or nuances that make up a life, I spoke aloud the only possibility I could think of. "Is she a bad person?"

No, my brother was saying to that little girl over 30 years later. Our mother wasn't a bad person. She and my father had made choices that were truly damaging but not with the intention of harm.

Intention. That one word holds all the difference, doesn't it? Here I think of Donald Trump as he lies, grabs, rages, tweets, and tantrums. As he fills every sector of the henhouse with foxes. As he strips away protections and rights, and does very bad things to children. It seems to me the most stunning thing about our current president is that he's made entirely of mean — and yes, racist — bones.

In an article published in Psychology Today in the first days of Trump's presidency, psychotherapist Stephanie A. Sarkis defines gaslighting as "…a tactic in which a person or entity, in order to gain more power, makes a victim question their reality," and warns, "It works much better than you may think."

Gaslighters set up a precedent by telling blatant lies. "Once they tell you a huge lie," Sarkis writes, "you're not sure if anything they say is true."

One such lie, common to gaslighters, is to deny having said something that you know, and can possibly even prove, they've said.

"…The more they do this, " Sarkis tells us, "the more you question your reality and start accepting theirs."

Another ploy is to claim that everyone else is lying. "...It makes people turn to the gaslighter for the "correct" information—which isn't correct information at all."

"They know confusion weakens people," Sarkis explains. "Keeping you unsteady and off-kilter is the goal."

"Trump denies he said something that he said on a tape that everyone has heard," reads a headline in the Washington Post.

"Journalists are among the most dishonest human beings on Earth," he claimed on his first day as president. He says it so often, I heard it again just days ago before I sat down to work on this essay: "…we certainly don’t want to stifle free speech, but that's no longer free speech. See, I don’t think the mainstream media is free speech either because it's so crooked, it's so dishonest."

Does Donald Trump believe there were airports during the Revolutionary War? Or that Frederick Douglass is alive and active today? Until recently, I'd scoff and sputter at Trump's idiocy whenever he made blunders like these, but I'm starting to see it as tactical. He isn't interested in having us accept that there were airports in this country 130 years before the Wright Brothers' first flight, nor that a man born over two hundred years ago is currently advocating for civil rights. He's interested in having us give up on the idea that details, accuracy, and history are of any consequence at all. For without these to check against, to hold up as a mirror, no one — least of all he — is accountable.

"His words are so often at odds with the truth that they can appear ignorant," Former Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright, says of the president, "yet are in fact calculated to exacerbate religious, social and racial divisions."

Trump's words are indeed at odds with the truth. Just as often they are at odds with meaning. Are the incoherent tangles that come out of his mouth in lieu of sentences the best he can do? I used to think so, but I've come to agree with writer Lindy West that this too is purposeful, that "Trump has weaponized nonsense." By turning language into something jumbled and befuddling, he's commandeered the very tool we use to think.

"Mama," my parents and yours likely said to us as babies. "Daddy." They first taught us about the world and our place in it by giving us names for our people, our family. The words our parents gave us are true, we assume. Thus we experience the world as a safe, comprehensible place.

"I have something important to tell you," my mother said on our revelatory trip to San Francisco, and my senses sharpened. I saw the varying threads in the carpet, felt the spiraling pattern of nubs on the bedspread, noticed the breeze from the open window that, in that far-flung city, was chilly in July. I felt certain one of us gathered in that crammed hotel room was dying.

"Tina and Steve are my children," she said instead, and I stared at her.

"Then who am I?" I asked, genuinely needing to know.

"Children must all find out eventually that their parents have blatantly and consistently carried on a lie for a number of years," Huffington Post reporter Anna Almendrala cautions in an article questioning the wisdom of pretending to our kids that Santa is real. "… If adults have been lying about Santa… what else is a lie? If Santa isn’t real, are fairies real? Is magic? Is God?"

But unlike parents who — for the sake of nostalgia, tradition, community, and the sheer fun of it — choose to include their children in the Santa fantasy, the adults in my family had hard work to do. They had to alter what they themselves believed. My mother and her first husband needed to convince themselves that Steve, at seven years old, was capable of deciding for himself who he should live with. Three years later, my parents had to tell themselves that Tina would be glad to find out she'd get to stay out west with her brother and father. When, instead, she cried on the phone and begged to come home, they must have assured themselves she merely needed time to adjust.

This leads me to wonder about the federal government lawyers who stated in court that children caged at the border aren't entitled to toothbrushes and soap. What do they tell themselves about those devastated children torn from their families at the gate? What goes through their minds as they put their own children to bed?

"The men and women who manufacture the trigger mechanisms for nuclear bombs do not tell themselves they are making weapons," Susan Griffin writes in "A Chorus of Stones," a book that explores the connection between secrets of war and secrets in families. "They say simply that they are metal forgers. There are many ways we have of standing outside ourselves in ignorance."

In what may be his one honest moment on record, Donald Trump once told a biographer, "I don't like to analyze myself because I might not like what I see."

Likewise, if there's one thing I learned from growing up in my alternative facts family it's that, in order to be effectively lied to, you often have to lie to yourself. The night after my mother told me the truth about her other children, I lay under the stiff sheets of my hotel bed and found I could remember every slip-up and hint. The times I'd seen my mother pore over Tina's letters, then quickly tuck them in her apron pocket when she caught me watching. The way she referred to Steve as Stevie like a little boy.

Details like these kept coming, as though I'd tucked a neat file of unexplainable memories away and now finally held the cabinet key. I want you to meet my mom, Tina had said to a friend we'd bumped into on Taylor Street just that morning. I found it odd when it was my mom who responded with, "Nice to meet you," but I told myself it was just a form of shorthand. That Tina simply found it easier to say my mom than my father's cousin. Slowly, I came to realize that I'd always explained away moments like these to myself, which meant that part of me had actually almost known.

There are many ways we have of standing outside ourselves in ignorance.

I needed my parents — two people who told me easily and often that they loved me — to be credible, so I worked to make the mismatched pieces of information they gave me fit together. I accepted the alternative facts they provided, even when the evidence clearly contradicted what they said.

I imagine this is something of what it's like for the voters who chose Donald Trump in 2016. He was famous, rich, and already imbued in their minds with authority. Right in there with the hate he spewed and the divisiveness he stoked were his assurances that he'd bring this country back to a time they wistfully remembered — It'll be great. Trust me. Believe me. I'm the only one who can fix this — a time when they knew themselves to be, as I did in my family, the favored ones.

Back when I thought Andra was my only sibling, I understood myself to be the only child of either of my parents by blood — their "real daughter" as we said in those days, which in our house meant the more deserving one.

Here is where, in the Venn diagram of privilege and culpability, I overlap with Donald Trump's base. Like me, they were raised to believe that, through a mere accident of birth, they are more worthy. I was raised to see myself as more worthy than the adoptee whose presence my mother resented, they to see themselves as more worthy than anyone who wasn't born white and who wasn't born here.

When I learned of my mother's other children, what I needed to know wasn't just where I fit in this new configuration of our family, but who I actually was. Perhaps to the MAGA rally crowd that's how it felt when the demographics in our country first began to shift. Rage doesn't start as rage, but as fear.

It was painful to witness the ways in which my mother mistreated Andra. Because I was close to my mom, I held onto a vague and wordless sense that I was responsible for what she did. Yet I never questioned my parents about how hard they were on my sister. It would have meant pointing directly at the imbalances between us, imbalances that I viscerally understood kept me safe.

I adored Andra, who died at 25, but I never asked her about what she went through at home, on the streets, or as a child in New York City's detention system. I wasn't ready to face the stark details of her experience, but I couldn't have said so at the time. As I imagine must be true for Trump supporters in regard to the many people they've deemed other, I simply didn't let myself feel curious about my sister's life.

Thankfully, I did eventually begin to ask questions, which is, of course, how empathy deepens and critical thinking begins. This is the more fortunate side of having been lied to as a child. Or it's probably more accurate to say that it's what's fortunate about having been a child to whom secrets were finally revealed. I discovered a place within me where I recognize when facts don't line up, a place where, if I listen closely, I'll find access to an important unarticulated truth.

I'd like to think that as Trump continues to strip his loyalists of their hard earned tax money and their healthcare, as he fails to bring back the jobs they lost as the world evolved around them, some may finally tune out his antics and bombast long enough to find that quiet place inside themselves. Then maybe they'll notice the fissures and contradictions, the hatefulness and downright cruelty in his version of the world.

"Don't confuse me with the facts," my brother quipped as he drove us down a desert road one afternoon a decade ago. I laughed and looked out at the wide clear sky he'd grown up under without me. We'd suffered devastating losses by then and racked up what could seem like countless missed opportunities. But for the moment, we'd put such thoughts aside. Steve looked well and felt strong. I flourished in the closeness we'd found despite the distance and the many years between us, despite our many years apart. He switched on the radio and we heard the resonant voice of our president — a man who was capable, eloquent, compassionate, and wise. This would be the last year I had the great gift of being someone's sister, but I didn't yet know it. There was so much up ahead I didn't yet know.

Shares