Democrats are beginning to reckon with the fact that, right now, the story of the 2020 election looks likely to end with Joe Biden being elected president.

That is very far from saying that Biden is a sure thing. Early frontrunners stand a pretty good chance of becoming a party’s presidential nominee, as Hillary Clinton did four years ago. But Democrats can look to their own past for a legendary example of a frontrunner who was viewed as a consensus, “moderate” candidate and who went down in flames.

That happened in the tumultuous election of 1972, when Richard Nixon was running for re-election. He appeared beatable, thanks to a weakening economy, accusations of corruption (although the Watergate scandal hadn’t begun to dominate the news) and continued civil unrest. On the other hand, Nixon had substantive foreign policy achievements: He was winding down the war in Vietnam and opening diplomacy with China, which would lead to his famous handshake with Mao Zedong.

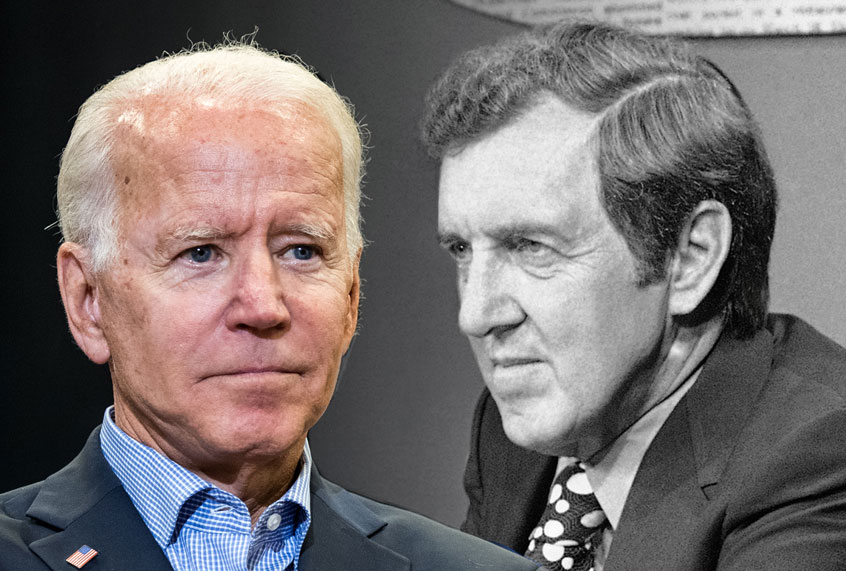

During the year before the election, Sen. Edmund Muskie of Maine — a laconic, inoffensive mainstream Democrat who had been Hubert Humphrey’s running mate during the 1968 election — led in most primary polls and tended to do well against Nixon in one-on-one matchups. Muskie was seen as acceptable to most factions of the Democratic Party, except the far left: He was liberal but not radical; he favored ending the war in Vietnam but was a staunch anti-Communist. His nomination seemed assured and a victory over Nixon was at least plausible. Much of the smart money in politics saw Muskie as the next president.

According to election lore, that all went south rapidly after Muskie was perceived, fairly or otherwise, as crying while talking to reporters on a snowy day in New Hampshire. One could unpack this incident as an artifact of that era or heteronormative expectations or the media hunger for sensationalism, but none of those things tells the whole story. The bigger thing that happened, as Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Theodore H. White points out in his masterful “The Making of the President — 1972,” was the emergence of George McGovern.

A World War II bomber pilot turned “prairie populist” senator from South Dakota, McGovern forcefully opposed the Vietnam War and had inspired a large, passionate grassroots left-wing movement that wrested the nomination away from Muskie and seized control of the Democratic Party. It wasn’t that Muskie lost; McGovern won. He pushed an ambitious platform of social justice at home and military de-escalation abroad that was more compelling to Democratic primary voters than Muskie’s argument that he was the safer bet to beat Nixon.

Much of the Democratic establishment despised McGovern, including the leaders of major labor unions and big-city political machines. Humphrey jumped into the primary campaign late to try to stop him, and when that didn’t work party leaders tried to convince convention delegates to pick someone else. McGovern won the nomination after a series of protracted fights — and gave his acceptance speech at 3 a.m., when most TV viewers were asleep. The end of the story is well known: Nixon won 61 percent of the vote and 49 states in one of the biggest electoral landslides ever.

There is a lesson here, and not the superficially obvious one — namely, that the Democrats should have chosen Muskie because McGovern was too far left to win a general election. In fact, neither Muskie nor McGovern understood their own political strengths and weaknesses, or what the Democratic Party needed in that election year.

Muskie didn’t realize that while Democrats wanted to win, they also badly wanted a candidate they could believe in. McGovern was no match for Nixon’s “dirty tricks” campaign, and allowed his opponent to shape the narrative of the election, which was that McGovern was a dangerous radical who couldn’t be trusted. He made matters much with his poorly-vetted choice of running mate, Sen. Thomas Eagleton of Missouri, who turned out to have a history of serious mental illness. Eagleton was dropped from the ticket a few weeks after the Democratic convention, a catastrophic gaffe that probably sealed McGovern’s fate. In the end, Nixon wiped him off the map not because McGovern’s policy ideas were bad, but because he had lost control of his own story.

That is the real lesson of 1972 that Democrats must learn in 2020, regardless of whether they pick the modern-day version of Muskie (that would be Biden) or one of the one of the two McGovern-style progressives in the race, Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders. (Or indeed someone else.)

If Biden wants to apply this lesson, he should pay attention to a recent column by a conservative Republican believe it or not. John Podhoretz, a former speechwriter for Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, recently observed in the New York Post that the press “all went crazy” after a single poll showed Biden statistically even with Sanders and Warren, after months of polling that showed Biden clearly ahead.

Podhoretz went on to mock supporters of Sanders, Warren and other less likely alternatives, but then made his real point: “Joe Biden is leading nationally by around 10 points in the poll averages. He’s in the lead in the four early states — Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada and South Carolina.” Biden has held those leads uninterrupted since at least April, Podhoretz concluded, and that’s not the kind of drama reporters and editors yearn for. “It’s boring. But it’s the story. The other stories are not stories. They are acts of desperate wish-fulfillment.”

I don’t share Podhoretz’s politics or his dismissive attitude toward the non-Biden candidates, but he’s right about two important things: If the status quo holds through 2020, Biden will get the nomination, because his story right now is about a candidate poised to win — not just the nomination of course, but to defeat Donald Trump next year. Most polls consistently show Biden beating Trump by sizable margins, usually by larger margins than any other major Democrat. It’s the Ed Muskie strategy, which could well have ended, with a few minor historical tweaks, with Muskie in the White House in 1973. That’s what he’s been able to do so far, and if he keeps it up he will probably be our next president.

But the Muskie strategy has obvious pitfalls, and it’s certainly possible that either Warren or Sanders could play the role of McGovern in this campaign. If one of them actually defeats Biden, the next task will be to control the narrative, framing their ambitious reform agenda as optimistic and urgently necessary — since there’s no doubt that Trump will depict it as a “dangerous” experiment with “socialism.” They will also need to attack Trump as corrupt, destructive and incompetent — exactly the same things that the Democrats needed to say about Nixon in 1972. Finally they will have to avoid the kinds of stupid blunders that can easily sink an insurgent candidate, the way the Eagleton fiasco sank McGovern.

Polls currently suggest that Warren and Sanders are less likely to beat Trump than Biden is, but that’s certainly not evidence that they couldn’t pull it off. Whoever becomes the Democratic nominee must learn the lessons of history. Joe Biden can be our next president if he learns the lessons of Ed Muskie’s defeat. Warren or Sanders could be our next president if they learn the lessons of George McGovern’s defeat. Those who don’t learn the lessons of history … well, you know how that one goes.