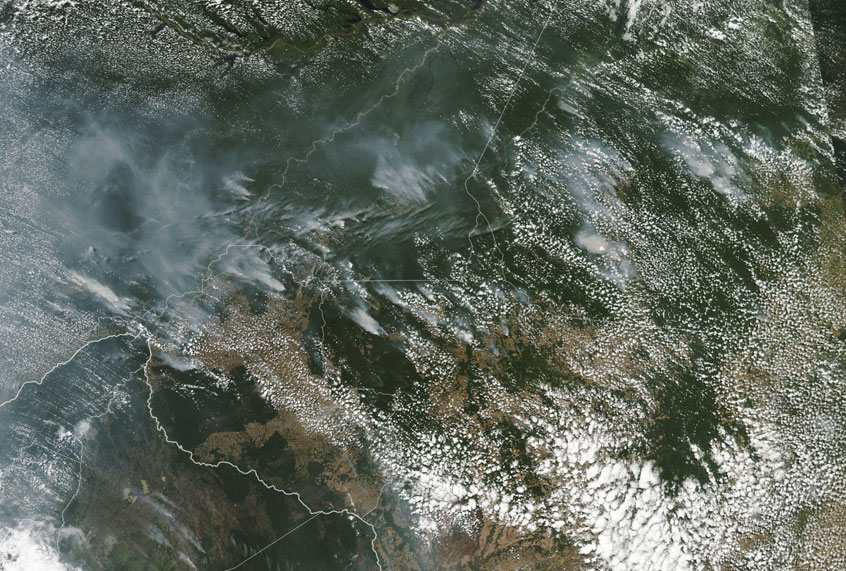

By now, you’ve almost certainly heard that the Amazon is burning. The hashtags #PrayforAmazonas, #PrayforAmazonia, and #AmazonFires have been popular on Twitter in the past few weeks, and shocking photos of the rain forest aflame are making the rounds. It’s bad.

Today’s international society functions like a giant ecological food web. Perturbations at one end ripple across the global economy and have unpredictable consequences, making it imperative for individual countries to have sound, well-considered economic policies.

But in his typical “I know better than everyone” approach to policy, Donald Trump provoked a trade war with China as soon as he was elected president of the United States. The heightened tensions between these two countries have shifted the movement patterns of agricultural products around the world, particularly soybeans. As of 2015, purchases from China accounted for 60% of U.S. soybean exports. But as a result of the escalating trade war — including a 25% duty on U.S.-grown soy implemented in retaliation for the Trump administration’s tariffs on Chinese products — U.S. exports of soybeans to China declined by 98% in 2018.

The beneficiary of the U.S.-China agricultural spat? Brazil. They have provided the bulk of China’s soy imports since Trump first proposed tariffs on China in April 2018. Although Brazilian soy exports to China had slipped a little earlier this year, they spiked again in mid-May after another round of failed U.S.-China trade talks.

But Brazil needs more agricultural land on which to plant enough soy to meet global demands — land which the country’s new president, Jair Bolsonaro, is more than happy to take from the Amazon rain forest. To be fair, Bolsonaro has not publicly directly ordered that the Amazon be cleared for cultivation, and this problem does pre-date him: deforestation of the Amazon for soy (and agriculture in general) has been happening for decades. However, like his U.S. counterpart, Bolsonaro is notoriously anti-environment. His Minister of the Environment disingenuously claims that the way to save the Amazon is by opening it up to logging and mining. And after Brazilian officials allegedly looked the other way when they were warned that local farmers planned to set a series of fires to “show the president that we want to work,” Bolsonaro floated the idea that NGOs were responsible for the fires.

Amazonian fires can occur naturally, and in the past they have been mainly linked to very dry periods caused by El Niño. But the current fires are different. Like the major fires that are currently raging in the rain forests of Indonesian Borneo and Sumatra, they are intentionally lit by farmers and land developers to cheaply and quickly prepare land for planting. The occurrence of human-ignited fires on top of increasing deforestation (which makes forests drier) combined with warmer, drier weather means that today’s forest fires are larger and more frequent than they have been in the past. Ecologists have even declared this to be a “new Amazonian fire regime.”

This was all foreseeable: Trump’s willful ignorance contributing to an ecological disaster (not to mention an economic crisis for U.S. farmers), the ignition of the Amazon, and Bolsonaro’s gleefully callous response to the fires. Brazil’s contribution to the global soybean market has been growing steadily since the 1960s, and surpassed the U.S. as the crop’s main global exporter in 2013. Crops, and the roads needed to transport them to ports, have to go somewhere, and the Amazon rain forest is a huge expanse of fertile land. Scientists from Germany’s Karlsruhe Institute of Technology even warned us about the soybean-fire problem in late March.

The environmental costs of our failure to heed this warning are huge: 10% of the animal species on earth are found in the Amazon, and scientists estimate that the Brazilian fires have already released as much carbon dioxide into the air as the annual emissions of at least 22 million cars. The fires are also a human rights issue; the territories and lives of Brazil’s Indigenous populations are at grave risk. Last week Bolsonaro sent the Brazilian military into the Amazon, a move that many believe is really designed to forcefully take Indigenous lands under the guise of “firefighting,” given his genocidal language and targeted campaign againstIndigenous communities and the fact that the military has been deployed to their territories. Although they deserve a huge portion of the blame, the soybean and cattle industries, and even Jair Bolsonaro and Donald Trump, aren’t solely responsible for the destruction of the Amazon. Dark money and shady companies with political connections to anti-environment politicians, including Donald Trump and Mitch McConnell, were a problem before Bolsonaro was elected. Major international banks and even furniture and shoe companies also contribute to deforestation.

The conservation of the Amazon rain forest, as well as other natural wonders, will always be as much a political and economic problem as an environmental one — let’s hope the trees are still around when we solve it.