The current whistleblower case dominating headlines is unprecedented, as intelligence director Joseph Maguire made clear last week, because it implicates the President of the United States. Yet that’s what whistleblowing is all about — empowering individuals to sound the alarm against powerful people and institutions. No one is more powerful than the President. Unprecedented as it may be, the differential in status between a lone CIA agent and the Commander in Chief shines a bright light on exactly what whistleblowing is intended to do: to place a check on power.

In both the private and public sectors, employers far less mighty than the President hold a great deal of power. Employees often do not realize that, while they are at work, they set aside many of their protections of free and open expression. Citizens are guaranteed their free expression of religion, speech, and assembly in their home and civic life, but employers can set strict limits on those rights in the work-for-pay relationship.

For example, although Americans enjoy wide latitude in what religious clothing they can wear or religious words they choose to speak in public, workplaces need only establish a minimal burden created by employees expressing their faith in order to justify a ban on yarmulkes, headscarves, and biblical phrases at work.

This is just one way that employers hold tremendous power over employees. Workers voluntarily enter the workplace, accepting to take on a job in exchange for a paycheck. Through various workplace protections — timed limit to the workday, overtime pay, health and safety statutes, non-discrimination rules — there are constraints on what employers can demand. Within that context, however, workers largely must do what their employers require of them. After all, employees always can exercise their “exit privilege” and are considered to be serving in their roles by their own choice.

This way of thinking about employment overlooks the material needs that people have to make ends meet, to provide for themselves and family members. People need jobs for income, and additionally for satisfaction and sociality. Work choices are seldom fully free. Yet, the presumed voluntary nature of work gives employers a lot of latitude to determine what workers do, what they can say, and what they cannot say.

The other side of this voluntary exchange of work for pay is that employers can, with very little justification in many states, choose to let employees go or fire them. This sets up a workplace dynamic in which workers must always think carefully before speaking out against people more powerful than they are in order to preserve their livelihoods and professional reputations.

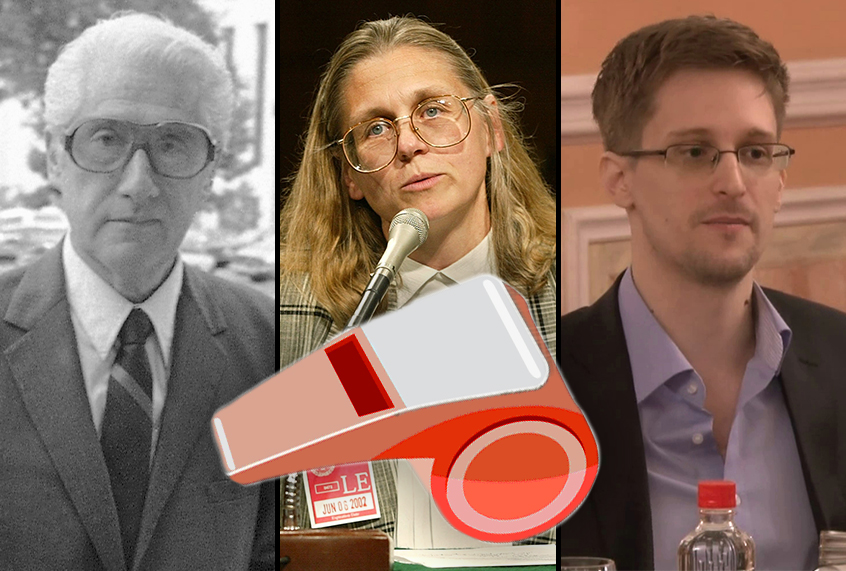

In the ordinary workday situation employees don’t carry whistles; instead, they carry out the instructions given to them by their superiors. But whistleblower protections provide a check on this whole system. Like the red button on a train, activating the whistle (or button) brings the machine to a total halt. Like a safety button, whistleblowing is meant to keep the workplace, or an employer, from going off the legal or moral rails.

The majority of whistleblower cases do not include high-profile executives like the U.S. President or a famous C.E.O. Many never make the headlines beyond, perhaps, their local media. In my area of metro Atlanta, for example, we have seen a whistleblower in healthcare who said his hospital was inflating medical bills—and was fired. A county officer claimed her department engaged in rigging bids for county contracts—and was demoted. A Georgia National Guard official believed she was fired for raising ethical concerns about her boss, a state senator appointed by the then-governor.

These and many other employees have raised the alarm through a process in their own organization or with an outside party because they believed they had a moral or legal requirement to speak up. Stopping the workplace train always comes at a cost, and there is usually little reward to be gained for doing so.

Most often, whistleblowing is an act of courage. Always, it slows down the organization or the public surrounding it to take stock—to determine if there is a moral or legal problem that must be addressed directly before the ordinary production or governing process cranks up again. In that sense, whistleblowing is a tremendously important safety check on power, and whistleblowers serve the very institutions whose leaders most often find them to be an annoyance.