In the summer of 1980, three young women hitchhiked to southeastern West Virginia, en route to the Rainbow Gathering, an outdoor festival set up in the woods in rural Pocahontas County drawing hippies and other peace-loving folks from around the country. The women never arrived. Vicki Durian and Nancy Santomero were found dead from close-range gunshot wounds in a remote part of the county. Thirteen years of suspicion, silence, and accusations swirled and tightened around a group of nine local men before one of them, Jacob Beard, was charged with the murder of the two women. Meanwhile, serial killer Joseph Paul Franklin's prison confession in 1984 was ignored until the late '90s, when Beard was granted a second trial and acquitted.

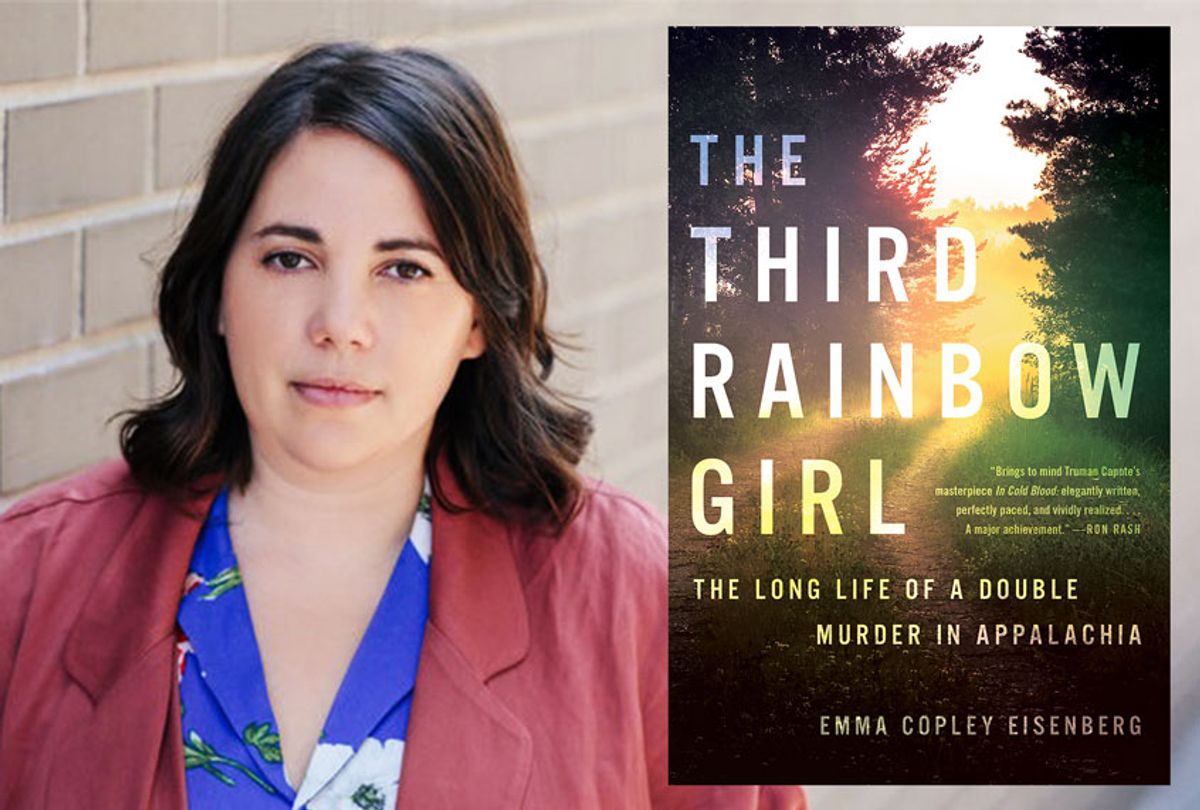

These are, as Emma Copley Eisenberg writes on page one of her compelling and sensitive nonfiction debut "The Third Rainbow Girl," true things, which is to say, they are facts about the crime dubbed the Rainbow Murders. As any student of crime, or life, knows, facts and truths can live side by side and still tell their own stories.

Eisenberg, a New York native, moved to Pocahontas County after college, about a decade after Beard's acquittal, to work as a VISTA volunteer charged with empowering local girls in an academic, college-prep enrichment program. "By days, I served teenage girls," Eisenberg writes. "But by night, starting in the fall after the camps ended, I hung out, learned to play bluegrass music, and drank beer with a group of grown men."

During that year she heard about the Rainbow Murders, a story that would stick with her and bring her back to West Virginia on many subsequent trips to try to make sense of the crime and the stories that grew up around it. In her book, Eisenberg dives deep into the mechanics of the investigation and both trials, how and why the vines of gossip grew unchecked over the years, well as the story of Franklin, the outsider who was not taken seriously as the answer to the unsolved murders, so deeply convinced were enough people that the killer had to be a local. At the same time she brings the lives of Vicki and Nancy, two young women who followed their own lights, back into focus. The third Rainbow girl of the title — the other hitchhiker, the one who lived — tells her story as well.

"The Third Rainbow Girl" is not only a meticulously investigated story of a crime and its haunting aftermath, it's also a coming-of-age memoir examining that pivotal year in Eisenberg's life embedded in a community marked by the trauma of the murders, when the girls she tutored would disappear from the college-focused demands of her program but not from town; and the man she was in a relationship with couldn't articulate what he wanted besides her; and a thrum of discontent built up in her as she began to see her work as increasingly inadequate to the task. "I was failing with men like I was failing with girls and I was failing to bridge the space that seemed to separate them" she writes. "You cannot treat women only for a disease of which men are the main carriers."

I spoke with Eisenberg by phone this week about her role and responsibilities as an outsider writing about an often-misunderstood region, what true crime can do for social justice, and the failings of poverty-alleviating programs like VISTA on the problems they were designed to help solve.

Our conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.

Appalachia is often either overlooked or misunderstood by people who aren't from there or who haven't lived there. And so I always appreciate a book that tries to grapple with the complexities of the region and not "other" it in that way that is often damaging.

I tried to make really clear upfront that I'm not native to the area, it's not a place that I can claim as mine. I began occupying this position of being in the middle, of being really close to a place but not being from there. So it's this kind of neither-nor feeling. I tried to write the book from [that place] — being like, I'm not from there, and I also got to spend significant years there that were really important and changed my whole artistic consciousness, political consciousness, all of that.

Did you find yourself kind of walking a line there? It seems like there are both opportunities and potential dangers in writing about the identity and the character of a place when you are outsider, but also seeking to be accepted. As a writer, what was that like to try to navigate the identity as both an outsider but somebody who was living there and consciously engaged with the community?

I feel like it's really complicated and it leads to a lot of feelings. You're not properly in any identity that makes sense.

I didn't come to this story as a reporter. I didn't find out about this story and then move to West Virginia to cover it. I wasn't a professional reporter. I was just a person who, for my own reasons, ended up moving to the region under the auspices of this national service program called VISTA, which is expressly stated to "alleviate poverty." It has a lot of complicated roots in Appalachia as a national service program that basically was started to respond to poverty in Appalachia. I essentially came to this place, into the story, as a person.

I love that distinction between "as a person," not as a journalist. [Laughs.]

I just mean that to say that I didn't intend to write this story, ever. I didn't intend to write it as nonfiction. I'm primarily trained as a fiction writer. Once I realized that I was drawn to and intricately entwined with this place and the people that I had known, and that I felt compelled to record or document that in some way, my first impulse was fiction. But I knew that that really wasn't going to work because of my position of not being from there. I think there's a lot more space in really rigorous nonfiction to make very visible and upfront who you are and how you approach the story, which in some ways is more difficult to make clear in fiction, I think.

I didn't think I wanted to write a book about murder. That was never my intention. As I became more and more deeply interested in figuring out why the experiences I had in West Virginia still were so present with me, I started remembering and paying attention to things that had happened in my time there. The murders just kind of stuck in my craw, as something that felt like a little microcosm of many forces and themes that had been present when I was living there.

I tried to be extremely transparent when I was reporting the story. I'm trying to get at a different thing, which is not necessarily the experience of being an insider there, but the experience of being someone who has moved through and has connected with Appalachia. I try to never position myself as speaking for. I think if anything I am trying to speak alongside other writers and creators who are from the region, and be in conversation with them, because there are so many amazing writers and thinkers coming up and getting more exposure in contemporary Appalachia. They don't need me to do that. It's a different story and it's a different position.

I'm always fascinated by writerly obsessions and the things that we can't let go of. What was it about this particular story that got under your skin so much? How did you first hear about Vicki and Nancy? How did you know you had to not just come back to the story, but come back to Pocahontas County and write about it in tandem with writing about your own experiences there?

I first found out about the murders at a writing group meeting. I feel like sometimes you don't know in the moment, but you look back in hindsight you're like, of course that makes sense. Writing is the thing that has most timed my path in the world. As I talk a little bit about in the book, Pocahontas County has a really rich and diverse and complicated body of people who live inside it. Many of those people are local to the region for generations, and many of them are also immigrants from cities and other places who either came there during the Back to the Land movement or shortly thereafter.

It was at a writing group meeting with a group of mostly similar aged folks, all of whom are writers. Some of them are local to the area and some of them are in that immigration category. One of them shared a poem that he had written about finding the bodies of two dead women and then he began to cry. It was clear to me that that was a real thing that really had happened. I knew him as the dad of a young guy who was my friend who I hung out with a lot. It was very clear to me that the physical trauma of finding these people in the place where you live was really still with him. Then I learned more about the crimes, much later.

At the time, I didn't think too much of it. I was very absorbed in getting to know the place and playing bluegrass music and trying to do a good job at the organization where I was working to "empower" young women. It's one of the things I think you look back on later and you're like, what happened with that?

Once I moved away, I was getting my MFA in fiction in Charlottesville, Virginia, and the Rolling Stone rape on campus article came out. Shortly thereafter, Sage Smith, this young black trans woman, went missing. There was very little coverage on it. Charlottesville was really starting to have a conversation about race and class. A couple of other things happened in Charlottesville at that time. That was 2014, 2015. It kind of felt like the culture wars around sexism and white supremacy were descending on Charlottesville as a microcosm of all these things that were to come.

I felt woken up and alive to wanting to participate in that conversation about these questions through nonfiction. I just couldn't bring myself to write fiction anymore in that moment. It felt too urgent. I started to write and think and journal and wonder why, again, West Virginia was still on my mind when it came to some of these issues.

I remembered hearing about this crime and then I started reading whatever I could on the internet about it. From the first moment that I read about the way these crimes had been documented or reported to the public, I knew that something was off. Something just rang very false. I had that impulse of someone is getting this wrong, and I want to do a better job or I want to know what has gone wrong here. The narrative of the crimes was so black and white and so flat, all about how these hippie women had been murdered by backwards West Virginian men. I think the themes of sexism and gender and inside/outsider lit up all over my brain cells that had been thinking about these things for a long time.

You went through an evolution about who you believed really murdered Vicki and Nancy. I thought that was interesting because on one hand this is billed as an unsolved murder, and yet there's also a confession, and yet that's also perhaps an unreliable confession.

I think that process in some ways really mirrored the development of my thinking, to which I'm very grateful to the material and all of the people that spoke with me for that, for pushing me forward and changing my mind in that way.

I think when I first started writing or interviewing people for the book, I thought that, yeah, it was probably this local guy, this farmer [Jacob Beard, the local man convicted in the first trial and acquitted in his second]. People kind of didn't like him. He was kind of weird. He maybe had done some shitty things to his ex-girlfriend, that kind of thing. So people were like, he probably is a murderer. He was someone that lived in the community and people had really suspected of committing the crimes for a while. I believed that at first because that was the only information available.

[But] I think that story revolves around you [having] to accept that this local farmer, a guy in his 40s at the time, would have just picked up women hitchhikers who he didn't know and then murdered them for no reason. Sex and rape was always alluded to, but Vicki and Nancy weren't sexually assaulted. There was always something about that that just didn't make sense.

As I talked to more folks and dug more deeply into the material, I stopped identifying with Vicki and Nancy as victims as much, and started more identifying with the very complicated and difficult realities of being a local guy at that time, many of whom were accused of doing these murders at one time or another, and just feeling more confused and then outraged over the way that this investigation ruined a lot of people's lives. The investigations and the behaviors that happened after the murders had a huge effect on people. I started having a lot more empathy for people who were living in the county at the time and the ways that they may have needed to believe that someone local had done it for their own reasons rather than from fact-based reasons.

I think another part of that is my skepticism around narratives and stories about law enforcement and criminal justice started to grow and grow, the ways that we like a good story, we like a story that has a very easy flat theme, like "men are bad and they kill women."

Actually, sometimes crimes are totally random. Sometimes they're for no reason. Sometimes they're about mental illness. They're for any number of reasons that are true but don't feel narratively satisfying. I started to open my brain a bit more to those as well.

In my reading of the book, that ties into the story that America tells itself about Appalachia, and tells Appalachia about itself. This story can be taken as a metaphor: The story at first was painted as one in which evil was presumed to have come from inside the community, as being somehow innate to it, which was an assumption that was shared by a lot of local residents. Then when a serial killer in prison for murder all the way across the country confesses to the Rainbow Murders as well, it becomes a story about violence visited upon this rural area with real detachment from the outside.

Yeah, absolutely. Even though the history of West Virginia's — but also maybe more broadly, central Appalachia's — relationship with America and American capitalism is one of violence that's visited on Appalachia, I think that's sometimes similar to ways that sexism or racism gets internalized by women and people of color. I think it seems from the literature that's out there and from what people said that there's also a belief that being Appalachian is a shameful thing that can get internalized by people, especially if they feel they're bad or they want to believe someone in their community is bad or flawed or less than in some way. In some strange ways, they're almost looking for stories to confirm that, even though that's not in your best interest.

The violence mirrors the economic violence that's been done to the region for centuries.

Absolutely.

That was not a narrative that I thought was going to come out of what I guess could broadly be called a true crime book, even though that would be a bit reductive, as would be the case for most good true crime books. How do you feel about that label?

I feel really complicated about it, maybe similar to what you're referring to. I think that historically the term "true crime" has referred to a kind of storytelling which is mostly about what happened and who did it and enjoying the pleasure of finding out what happened and who did it. I don't identify, I guess, with that label for this book. As you can see when you open the book to the first page, all the facts are upfront. There's no spoilers really. I spoil it for you in the first five pages. If you're someone that reads to find out what happened and who did the crime, this probably isn't the book for you. That was on purpose, to say this is a different kind of book about a crime.

I'm certainly not alone in writing that kind of stuff. There's so many wonderful books out recently, including "Bloodlines," the book written by Melissa del Bosque, who actually just wrote my review for the New York Times, which was really kind, and Rachel Monroe's book "Savage Appetites," and too many to name. Bob Kolker's book "Lost Girls." I think it's happening and I'm excited to see it happening more and more, that modern true crime is becoming a place for socially engaged questions to be explored through crime stories, which we're seeing a lot of popping up in the last couple of years.

Like the "When They See Us" Netflix series and pieces exploring police [misconduct], mass incarceration, and death. The ways that crime has and always has been a lens to look at the questions of class and race and gender and all the things.

People talk about the true crime boom in a bad way, but I am also interested and excited to see that that label is becoming applied more and more to work that maybe does sell commercially, but also it is an exciting place for inquiry into those questions too.

Tim, the man who found their bodies, who you then meet in your writers group years later and hear him reading his poem about it — clearly, this episode has marked him in a really deep way. It's a pivotal moment in his life, and he's crying after he reads it. There's a real attention paid to men's internal and emotional lives in this book that struck me as significant.

Stories about this kind of crime often focus on the dead girl — to be painfully reductive, again — and what she means. But there are all of these men involved in this larger story. Did you set out to write a story about men? Because in a lot of ways, [in my reading of it] this is a story about masculinity and what that means for the men and their own quality of life, not just in how they impact the quality of life of women.

I went very to work with teenage girls to "empower" teenage girls through this program as a service volunteer, but I found that the people that I spent the most time with were guys in their 20s and 30s who were working really hard physically to get by and who had a lot of trauma for a lot of different reasons and who were navigating a lot of the same issues that the young women that I was constantly working with were also. And that the connection between the girls that I worked with and the young guys that I was mostly drinking and playing bluegrass music with, if I'm honest, they seemed really connected, but no one was making that connection. There wasn't a lot of space for empathy for the men in these communities.

I did feel that I tried to render on the page that masculinity in Pocahontas County, maybe southern West Virginia more broadly, isn't this bad, extra-macho kind of masculinity, per se. There's also a lot of ways that gentleness and care for each other is present in this community with these guys in ways I haven't seen between men in urban places as much. It's complicated. I saw things that were confusing about what they meant for masculinity and for me and my position in that space. I knew that that was part of what was driving me to write this book.

Certainly I began [from the perspective of] I am much more like Vicki and Nancy, I'm much more like Liz, who is the original "third Rainbow Girl," although the title of the book I think expanded to mean more than that. I thought I was writing a story of identification with an outsider woman, outsider in the ways that violence against women happens. But it turned out that I was actually writing something more complicated than that, which I think is about the ways sexism is a poison for everybody everywhere and that it's not just women who are suffering, it's not just people in Appalachia who are suffering, it's all of us and all of these connections in many different directions at all times.

Now that sense of both stands. I care and identify with the women in the story and I care and in many ways identify with these guys who are accused of the crimes, as well. Both of those things matter.

You've said the phrase "quote-unquote empowering" several times.

I know. I know.

Which is in your text, also, in the passage about how there was another way to belong to this community, to do the job you were brought there to do, to "alleviate poverty" as is AmeriCorps VISTA's proclaimed mission and to do so via "empowering" the girls in Mountain View, which you write you were failing at.

Can you talk a little bit about the role that programs like this are supposed to fill and then your experience and the reality of being assigned to the responsibility of "alleviating poverty" by "empowering" the girls of this community?

Essentially, I think that there is such a thing as service, there is such a thing as altruism, there are lots of organizations and a lot of good work that happens in Appalachia that I think do make people more powerful. And certainly young women are deserving of that service and deserving of those programs. However, I do think that particularly in Appalachia a lot of the money and labor that we funnel towards that idea of empowerment or that idea of service is not always effective.

AmeriCorps VISTA is a program that was launched to combat poverty in Appalachia in particular, as part of [President Lyndon B.] Johnson's War on Poverty, and that the effects of that longterm have been in some ways more damaging than helpful. There's a lot of ways that having people who are largely unskilled young people from elsewhere come into your community to "alleviate your poverty" is ... It's a difficult reality to accept and that does something to a community, I think, to continue to receive aid in that form.

I got a bit curious and then suspicious and then somewhat disillusioned with the idea of national service as it currently stands. I think there's a lot of really great opportunities and ways for people to serve in this country, to funnel dollars and labor towards Appalachia, but I guess I'm not convinced that the systems we currently have in place are working that well. I think that Appalachia deserves a really highly functional and targeted Appalachian Regional Commission that has enough funding to address the systemic problems that have to do with history, with hundreds of years of Appalachia being exploited for its natural resources. I'm not sure that service in the form of young unskilled outsiders can really accomplish what's needed to combat those historical injustices, if that makes sense.

Mountain View is what brought you to Pocahontas County, and brought you back again, and is this source of connection and also frustration for you in the book. The girl with the red hair who appears throughout the book, first as a summer camper and then as a member of the school year program, is a really compelling character. I'm curious about how you, especially coming from a fiction background into nonfiction, how you thought through the ethics of writing about students in nonfiction like this.

How do you craft a character while being aware of, and accounting for, that inherent imbalance of power that tilts in the writer's favor — in your case both in real life, but also in that relationship between writer and page and subject?

It's really hard. I think I made a lot of different decisions over the drafting of the book and changed my mind a bunch of times. I don't know if the end result is the perfect answer, but it's the answer I came to, which is that I wasn't going to describe or reveal information about any particular minors that would identify people that participated in the programs of Mountain View who didn't consent to appear in some lady's book. I did feel that it was important to represent some of the questions and moods and actions of the young people that participated in that space with me as they related to the case in the book. I tried to really ask myself always, am I putting in this detail just for the hell of it or am I putting in something that is relevant to the things I'm trying to explore and explain in this work? If it was the former, then I would cut it. If it was the latter, then it would stay.

I did make the decision at some point that if I was going to say anything more active and more specific about a young person that I had worked with, that I would essentially create one composite character who could contain specific actions and things that I had said or were said to me. That was the way I decided to make the writing compelling on the page without, hopefully, sacrificing the privacy of young people.

There is one person who is quoted at length in the book who is a native West Virginia trans man who participated in the programs offered by Mountain View who's now an adult and who had a different extended conversation with me and gave his consent to participate. If people are adults and have something to say, I included them. If they were minors at the time and couldn't give that consent, I wouldn't render them in specifics.

Thanks for talking with me today. Is there anything that I haven't asked about that you wish that I would?

I hope that people also read deeply in the literature that's coming out of the region right now written by people that are from there. I want to keep shouting out books like Elizabeth Catte's "What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia," Mesha Maren's novel "Sugar Run" that's really amazing that just came out recently. Carter Sickels has a novel coming out called "The Prettiest Star," and then my friend Catherine Venable Moore, who's an amazing nonfiction writer, has two books coming into the world soon. There are a lot of other people out there who are writing more deeply about the context that informs this book. I hope that we continue seeing lots of diverse and exciting thinkers and writers coming from the region writing about all of these questions.

Shares