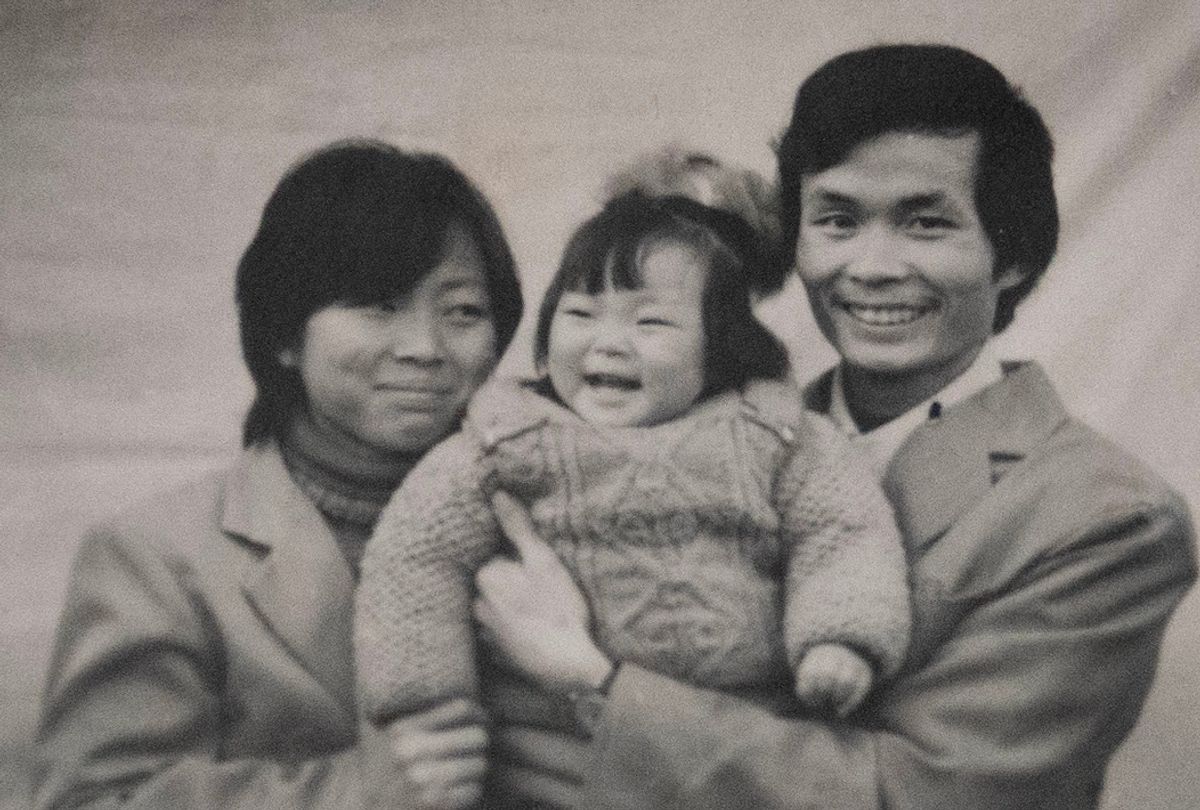

Documentary maker Nanfu Wang has a younger brother. That might not seem such an unusual fact, unless you know that Wang was born in China. In 1985.

Between 1979 and 2015, China dramatically curtailed its explosive population growth with a draconian edict limiting each family to a single child. In its gentlest form, the policy was enforced via a massive propaganda effort. In its more brutal form, enforcement tactics included destruction of offending families' property, as well forced sterilizations and abortions. The rules were somewhat more loosely enforced in Wang's rural community, hence the brother, but had he been born a daughter, Wang's sibling likely would have been abandoned and left to die. Countless other infants met a similar fate, while still others were brokered off to adoptive families in the US. For some children it was a rescue; for others, an abduction.

"One Child Nation" is a powerful, disturbing and beautiful story, a personal family odyssey with a political heart. And though we face a very different kind of tipping point as a nation and planet now, watching it, you can't help thinking of the moral tradeoffs of a crisis, and the chilling implications from the family planning enforcer who observes to the camera, "I had to put the national interest above my personal feelings. It was like fighting a war. Death is inevitable."

Salon spoke recently to Nanfu Wang via phone about the story she set out to tell, and how resonant its message is today.

This whole story was driven by your own experience of motherhood, and going back and looking at your family. What do you feel you didn't understand before you started talking to your family, talking to your mother, and what has that changed in your family dynamics now?

What I didn't know before was mostly the scale of the one-child policy and the consequences, because it was something that I didn't pay attention to. And of course by questioning that, I discovered a lot of the family history that I didn't know either. Some of the things that happened with my uncle and aunt and my cousin were surprising to me. In terms of how that changed our family dynamic, there was a lot of the change in that sense because, definitely, it was hard to talk about. That was something that they didn't like to bring up. But I felt like they appreciated that opportunity to talk about it. I could feel that, after I talked to them, they all had so much that they wanted to say and that they wanted to express.

It's something that was suppressed for a long time. It's interesting because, my mom, I feel like every time I make a film, she gets to know me better and she gets to know what I do and how I think. My family, we usually don't communicate anything outside of food and clothes and, "Are you warm? Are you healthy?" This project definitely brought us a lot of understanding, and a lot closer in terms of our communication.

Seeing how this experience affected your brother growing up as the son, and his understanding of the privilege that he had, must have been very interesting for both of you.

My brother and I are best of friends for life. But we never talked about the things we did in the film. It was a very, very emotional moment for both of us, because we've never directly addressed the privilege he had as a boy in our family and that I was deprived of because I was a girl or the sacrifice that I had to make. Not going to school, not going to college, and working to provide financially for him – all of those things we never spoke with each other, although we loved each other, we're best of friends. Because of that conversation on camera, I had to ask him how he felt about the one-child policy. When he said those things, he was almost crying. I was filming, and I was crying too. I think it's very special and very emotional for both of us. I was glad I did that.

It must have been a challenge, the way that you show the justifications for some of the things that happen in this story and the real moral gray areas. This is not a story where everyone is either a hero or a villain, particularly when it comes to the trafficking. But even before then, you're talking to your mother, and your mother is just absolutely, "This had to happen. If this didn't happen, there would have been cannibalism. There was no way around this." Although it was enforced brutally, the policy did not arise from nothing. It came out of extreme circumstances.

It's something definitely I thought about a lot. The reality when you encounter someone is, it's not black and white, although it's very easy to depict someone as black and white. When you are creating this story, it's much more difficult to bring out the complexity and the reality of the people themselves. But that's something that we strive to do, because we don't want to easily make perpetrators and victims and "These are bad people, these are good people." We try and establish that each character did something. It's so complicated. Under normal circumstances they might not have done that. In making the film, a lot of the times I tried to ask not what happened, by how. How does this happen? And why. I hope that the film can make the audience see the circumstances, and not just what happened.

It feels like a very unique moment for a story by a Chinese-American filmmaker to be coming out. There is so much misunderstanding, and so many misconceptions coming from a very high level in our government about Chinese culture and Chinese people. What do you hope this film now coming to PBS can educate the American public about life in China?

The complexities of the culture itself. In terms of like what I'm hoping for the audience here to take away . . . is about disinformation and propaganda. What I wanted to present was how propaganda made people do the things that they wouldn't have done. How did it work? How could it make millions of people be on board with something that is completely against their own self interests and their personal morality? This is not unique in China, although the policy is. Propaganda exists everywhere and disinformation even moreso. The current time is depressing and infuriating, to see the coronavirus unfold, and the response from authority. A lot has to do with disinformation. So hopefully when people see "One Child Nation" on TV, they are not only learning about the one-child policy from China, but they can watch it and question their own environment, reflect on their society and, and be open-minded, and always have doubts on what they are told and what authority says is true.

I'm wondering what it must feel like to you seeing China being scapegoated right now by our government, and seeing what is happening in terms of a rise in hate crimes.

I think there are many different misunderstandings, including the president calling it China virus. There are definitely people who believe that. At the other end of the spectrum, people now are praising China's handling of the coronavirus response because you can see headlines saying that China has been effective and the measures were good. That's also a misunderstanding, and showing how people don't really know what happened within China. They're only getting an image that the Chinese authority project onto the world.

"One Child Nation" is available for rental on Amazon Prime, and premieres March 30 on "Independent Lens" on PBS.

Shares