Desmond Meade stood before the railroad tracks and never wanted to feel anything again. "I was a broken man," he says now. "Even the thought of the pain associated with getting run over by a train did not make me move." But by blessing, coincidence or just some random delay, the afternoon train didn't pass through Miami that summer afternoon. And so Meade literally walked across the tracks and changed his life. A few blocks away, he happened upon a drug treatment center. He found a homeless shelter. Step by step, that "broken man" reassembled his life. He went back to school and became a paralegal, then earned a bachelor's in public safety, summa cum laude, and finally a law degree in 2014.

Meade's dramatic triumph, however, couldn't overcome one hurdle: Florida doesn't allow anyone with a felony record to vote. The Florida Bar won't admit anyone who can't vote. Even home ownership is impossible in most Florida communities without that basic civil right. By 2018, more than 1.68 million Floridians, according to the nonpartisan Sentencing Project — more than in any other state in America — faced a lifetime ban from voting, permanent except under extraordinarily rare circumstances, long after they'd completed their sentence.

Under these conditions, Meade couldn't practice law. He couldn't even cast a ballot for his wife, Sheena, when she ran for state representative in 2016. "In spite of the many obstacles I've been able to overcome, in spite of a lifelong commitment to giving back to my community, to making my world a better place," he says, with a shake of his head, "I still couldn't vote. It was a knife being twisted in an old wound, reminding me I'm not a full citizen."

Meade built that pain into a movement. As president and founder of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, launched in the early 2010s after nearly a decade of organizing work by the Florida ACLU, the Brennan Center and the Sentencing Project around restoring voting rights to former felons they prefer to call "returning citizens," Meade led one of the most impressive grassroots petition drives in state history. He inspired an all-volunteer army that collected 799,000 signatures statewide, enough to force a 2018 ballot initiative that would amend Florida's constitution and end this insidious vestige of the Jim Crow South.

(Florida's legislature would later require all associated fines and fees to be paid to the state prior to re-enfranchisement. Recently, a federal judge heard a challenge to that modern-day poll tax, brought by the ACLU and other voting rights groups. It may ultimately end before the U.S. Supreme Court.)

But first, in order to accomplish this seemingly insurmountable task, Meade assembled an almost unimaginable coalition—starting with his political director, Neil Volz. Volz, a longtime Republican, became a powerful congressional aide to U.S. Rep. Bob Ney after Republicans took the House in 1994, then swapped his access to the GOP into a job with super-lobbyist Jack Abramoff and landed inside the capital's shadiest influence-peddling shop. After pleading guilty to conspiring to corrupt public officials, Volz started over in Florida as a night janitor. One night, sweeping up on campus, he heard Meade speak, and realized that he was also talking about him. He signed on, and together, Meade and Volz united former felons and second-chance-believing churchgoers, tattooed Trump-voting "deplorables" and radical criminal justice reformers, black and white, into a mighty moral movement funded by both the ACLU and the Koch brothers.

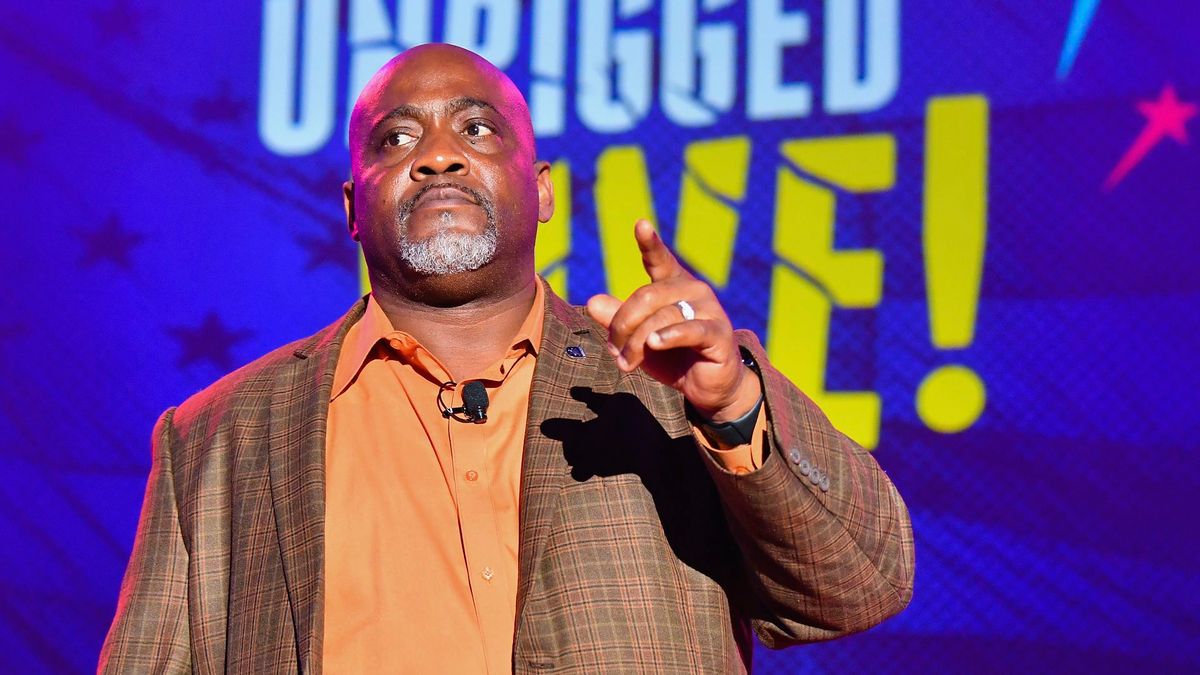

Now, on another swampy August morning, 13 years after Meade believes God's grace lifted him across those train tracks and toward rehab, he takes the stage at the FRRC's summer 2018 convening to the sound of raucous whoops and Eminem's "Lose Yourself," trying to will this unlikely political force across one more finish line. Meade thrusts his right st in the air and sings along: "Look if you had one shot, Or one opportunity . . . Would you capture it? Or just let it slip?"

For as long as blacks have had the right to vote, Florida has weaponized the law and used felon disenfranchisement as a tool to keep black citizens away from the ballot box. But this vestige of Jim Crow infects today's politics as well. Once freed, former felons tend to stay quiet about their conviction, making it that much easier to construct barriers between them and public life. Now those walls are coming down, having collided with another long-lasting American notion: fairness. The story of how it happened in Florida is one of the most inspiring and surprising political stories of our time. An ancient set of laws grounded in racism is being torn down, and though obstacles remain, a new civil rights movement has grown around a simple yet profound phrase: When a debt is paid, it's paid.

The passage of the Voting Rights Act and a series of landmark U.S. Supreme Court cases in the 1960s and 1970s began the long, bumpy road back to fairness in Florida and across much of the South. Much of that intermittent progress, however, was tragically interrupted in the 1980s by the "war on drugs" and its mandatory sentencing requirements, all of which disproportionately targeted communities of color. The statistics are stark: In 1976, 1.17 million Americans were unable to vote because of a felony conviction. By 2016, that number soared to 6.1 million, according to the Sentencing Project. Nearly half — 48 percent — of disenfranchised felons who have finished their sentence and paid their debt in full live in Florida. More than 10 percent of Florida's adult population can't vote; almost a quarter of the state's African American population are kept away from the polls.

Before Desmond Meade, no one in Florida was able to do anything about it.

* * *

In Florida, however, a message of racial fairness and amends for repressive Jim Crow-era laws is a tough sell during polarized times in a perpetually purple state. After all, in 2018, Republicans won two tight races: former Gov. Rick Scott flipped a U.S. Senate seat, and Republican U.S. Rep. Ron DeSantis narrowly edged Tallahassee mayor Andrew Gillum to become the state's next governor. The races were close: Recounts and legal battles extended well into mid-November.

Alongside these cliffhangers, Proposition 4 — Desmond Meade's Voting Rights Restoration for Felons Initiative — soared to victory with almost 65 percent of the vote. This was no accident. Organizers knew they needed to keep an issue infused with race and partisanship far away from those electric wires. A race-based appeal risked losing white voters. And if the proposition was seen as partisan, it could lose Republican voters.

In the years leading up to the vote for Proposition 4, the biggest nightmare for organizers was as follows: What would happen if opponents dropped a last-second TV ad along the lines of the shamelessly racist Willie Horton spot that rocked the 1988 presidential race, focused around heinous crimes by a black man and terrifying suburbanites of all parties? So they made that scary ad themselves, and showed the ad to a focus group just to understand what happened if voters were exposed to the worst messaging they could imagine. But polls consistently showed very few undecided voters on this issue; the challenge was keeping all these strange bedfellows in the same room.

"We needed to know what message people might hear that would make us lose their support," Jane Rayburn, a senior director at EMC Research, told me. This research guided one of the most internally divisive decisions of the campaign: continuing to exclude those convicted of sex crimes from voting. It also steered messaging that deliberately avoided any mention of racial equity. "This campaign is not about voting and it's not about voter suppression," Meade told volunteers in Orlando. "This is about second chances for people who have made mistakes — but those mistakes and going through those mistakes have made us much better people."

Whatever happened, they would be ready. EMC Research, a polling firm that works with Democratic clients, probed for the exact words that resonated with voters — and the ones that didn't. They tested to see if those messages were different in Miami than they were in Tallahassee or the conservative panhandle sometimes called the Redneck Riviera. They hired voter psychologists to further refine framing and even determine the right year to place the proposition on the ballot.

Initially, voters responded very well to the ideas of "fixing a broken system" and providing a "second chance" — so well that "Second Chances Florida" became the name of the campaign's website. "Letting felons vote?" This proved less popular. The word "felon," as you might imagine, polled poorly, so the researchers rephrased their copy, finally hitting on a description that worked: "returning citizens." When pollsters dug deeper to understand why the concept of "second chances" was so powerful, they found that voters across racial lines, party divisions and even religious differences especially liked that this second chance wasn't being given freely as an act of mercy, but had been earned by completing a sentence. Republicans, especially, liked the argument that it wasn't just the right thing to do; it was the smart thing. That led to the next layer of messaging, tested and refined into the most effective phrase: "When a debt's paid, it's paid." When I attended the August convening, pollsters had just finished an even deeper dig and learned the power of the word "eligible." The second chance wasn't simply being handed out for completing a sentence; it was an opportunity that had to be earned and then claimed.

"We want to stick to the message: giving the eligibility to vote back to people who have paid their dues," Rayburn told a large crowd of "returning citizens" at the convening. "What we know from the research is that the message we're using resonates with everybody. So anything that's not on message is off message. Even if it feels persuasive to you — if it's off message, it's off message." Rayburn's job that day was to teach a crowd of political rookies with criminal records how to talk to friends and neighbors, because polling also showed that this message worked especially well one-on-one. Maybe people don't want a rapist to vote. But John next door, who made a mistake in his 20s and paid the price? Of course he should vote.

"Personal stories are the most compelling," Rayburn told a rapt room. "They all feature returning citizens. You share that in your own words. Then you pivot to the message triangle. Our system is broken. My debt is paid. It's paid."

Rayburn tells me she's rarely seen a single word make such a huge difference. The evolution even from "second chance" to "eligibility," she explains, seems like a small nuance but actually changes everything. "It's funny," she says, "we've done four years of research to drill down on this one word. Eligibility. 'After you complete all the terms of your sentence, you can earn back the eligibility.' That one word is extremely important. I mean, that's what this amendment does, right? It does not automatically put people in the voting booth. It gives people the eligibility back."

The messaging that doesn't work? "Making it about 'the right thing to do,' " she quickly answers. "Making it a partisan issue. Because it's not. That messaging doesn't work and it's something the campaign has been really disciplined about. Across party lines, racial lines, geographic lines, people feel that if you have paid your debt, the debt is paid. We've made sure that this is an inclusive campaign."

This dedication to inclusiveness is why one of the faces of Second Chances is Brett Ramsden: thirty-six, white, confident, soft-spoken, slender, with the look of a sun-kissed Homecoming King to whom everything comes easy. Only Brett spent a decade hooked on opioids, effectively trashing what might have been a promising baseball career, feeding his addiction by stealing from his family and committing a string of break-ins. He wrecked three new trucks in drunk-driving accidents. "I racked up eight felonies in one summer and didn't spend a day in jail," he said. "I should have had 50." One judge after another saw a clean-cut white man and pushed him toward treatment. Finally, after turning up high to court dates, after passing out in a Burger King, after getting busted returning groceries to Publix with an old receipt and shoplifting fishing gear from Walmart, all for opioids and crack, he accepted help, walked into a Naples church and heard the voice of God. "Welcome back, Brett," said the voice, washing over him. "Where've you been?"

"There's value in my story," Ramsden tells me outside the hotel's Starbucks. "When you think about an ex-felon, a certain image pops into your head, you know? Maybe it's a gangbanger or a guy with pants hanging off his butt. Ultimately, it's a black guy with a gun. There's power in someone that looks like me getting up there and saying, 'This affects me too.' And it's not just me. Sixty percent of those 1.4 million people that can't vote — they look like me as well, even though a lot of us have been told our entire lives that this is a black thing."

Ramsden laughs when I ask if it ever occurred to him that his Walmart larceny spree would cost him his voting rights. That high, he says, "you can't see past the next hour." Now, however, as he struggles to get a state professional license to help other recovering addicts, can't put his name on his family's apartment lease and wants to support school board candidates making decisions that will shape his young daughter's future, he deeply regrets losing his vote. "I made very poor decisions," he says. "I'm trying to help and give back, but it's always there, for sure. For a little while longer, anyway."

* * *

Desmond Meade grabs a chair and surveys the bustle around him. He attended his first convening a dozen years ago and it was little more than the gathering of a small email list. Now this poor, formerly homeless African American male is about to do something unthinkable — end felony disenfranchisement at its very epicenter, and maybe even point the way toward a new kind of politics. "This is a shining example of how we can get things done in this country," he says, "by shedding the partisan labels and the racial labels and coming together at that sacred space where we are all human.

"They said this couldn't be done." He smiles. "What's so beautiful is because, other than voting, this is the second purest form of democracy in action. When people take matters into their own hands." When the constitutional amendment passes with 64 percent of the vote, my first thought is Meade's smile that afternoon, and that if his wife seeks office again, he can vote for her.

Shares