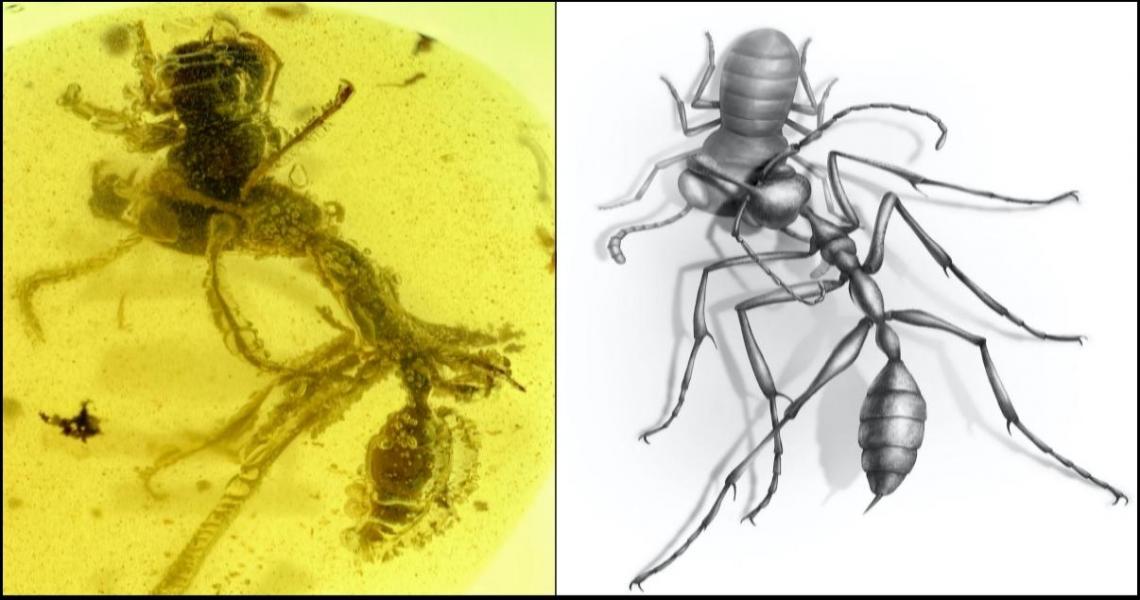

The idea that prehistoric animals may be trapped perfectly in amber, preserved for millions of years, isn’t just a staple of dino-cloning sci-fi franchises like “Jurassic Park.” On Thursday, scientists revealed a monumental discovery about the ancient world embodied in the discovery of a “hell ant” trapped in amber as it was in the process of devouring a baby cockroach.

A hell ant, or haidomyrmecine, is a relative of modern ants but with a critical difference: Instead of horizontal pincers that bite their prey, the hell ant had vertical jaws that resemble a scythe, which would pin its intended meals against a horn on their heads. The hell ant in question here managed to capture a Caputoraptor elegans, an insect related to modern cockroaches but which, like the hell ant itself, is now extinct.

“Hell ants are one of the earliest branches of the ant tree of life and their lineage arose prior to the most recent common ancestor of all living species,” Phillip Barden, lead author of the study and an assistant professor at New Jersey Institute of Technology’s Department of Biological Sciences, told Salon by email. “This is not unlike the relationships between extinct non-avian dinosaurs and the birds we have today.”

As the article in Current Biology makes clear, scientists are unsure why the unique vertical type of jaw seen in hell ants no longer exists today.

“The ecological pressures and developmental requirements that led to vertical mandible articulation are not yet known,” the authors write. “Also unclear are the conditions that drove haidomyrmecines to extinction after persisting for a period of at least 20 million years across present day Asia, Europe, and North America.” They note that hell ants may have been “susceptible to extinction during periods of ecological change,” though competition with other ants could have also played a role in their extinction.

Salon asked Barden to explain the larger significance of the study.

“This paper provides an explanation for why it is that we see diversity in the fossil record that is no long present today,” Barden told Salon by email. “At the same time, it also gives us a better picture of an extinct group of insects, which we can hopefully use to better understand how and why extinction impacts linages differently.”

Barden also pointed out that “although there are thousands of predatory ant species, no living ants capture prey in this way. That is, no modern ants possess horns of any kind or mandibles specialized in this particular way.” He also elaborated on what the ancient cockroach ancestor — which was a juvenile at the time it was devoured — must have experienced being preyed upon by the hell ant.

“The prey would have been essentially collared around the neck by the elongate horn and mandibles of the hell ant before most likely receiving an immobilizing sting,” Barden told Salon. “We think hell ants may have had very fast muscle movements, something we see in some modern ant predators, so the hell ant mandibles may have snapped closed in a very quick flash.”