On Saturday President Donald Trump issued four executive orders that provided an additional $400 in weekly unemployment benefits, backdating the payments so that they can begin retroactively on August 1. Shortly after doing so, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) released a statement blasting Trump's new policies as "unworkable, weak and narrow" and adding that, in addition to reducing unemployment benefits, it "endanger seniors' Social Security and Medicare."

In headlines, Trump's executive orders have been lumped into a few media talking points: First, the $400 additional weekly unemployment benefits, $200 lower than the previous CARES Act provided. Second, the word that Trump's orders will threaten Medicare and Social Security.

As always, the devil is in the details. Salon spoke to economists who broke down how these orders will affect the average American – working or unemployed, rich or poor.

1. Trump's executive orders were multifarious, and achieved several policy goals at once.

It is important to remember that Trump did not sign just one executive order, but four. In addition to extending unemployment benefits, the orders also extended federal protection from evictions, granted a payroll tax holiday and deferred student loan payments through 2020.

The ostensible goal of these measures was to provide relief for Americans who are financially suffering after the economy closed down in March as a response to the pandemic. Many conservatives, such as Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin, have argued that too much federal generosity could disincentivize people from working, even though studies have debunked this. Still, that unfounded belief is why some Republicans called for a reduction of the original $600 federal supplement to unemployment benefits.

Trump's federal protection from evictions, incidentally, was meaningless.

"My understanding is that it does not actually provide any protection at all from evictions," Dr. Jesse Rothstein, an economist at the University of California Berkeley, told Salon. "It directs a couple of federal agencies are studying what they could do to protect you. That's the sort of thing you might have thought they would figure out before he issued the order, not afterward. But it was just to study. It isn't gonna do anything."

Other economists have echoed Rothstein's observations.

2. Social Security and Medicare are at risk, although the situation is not entirely dire.

"The payroll tax cut removes some funding to Medicare and Social Security, but those funds can always be replaced with other revenue from the general fund so it's unlikely to cause any cut to outlays," Dr. Gabriel Mathy, a macroeconomist at American University, told Salon by email.

Right now, the payroll tax has been deferred, which means it eventually has to be paid. That does not in its own right put those programs in long-term jeopardy.

It is also important to note that, because Trump said he would make his temporary payroll tax deferral permanent if he is reelected, he is effectively arguing that Medicare and Social Security funds should be slashed. Payroll taxes are solely used to pay for those two social programs, and since Republicans traditionally oppose raising taxes, it is difficult to see how permanently eliminating payroll taxes would not jeopardize Medicare and Social Security.

"One of the limitations of executive orders is that they don't actually spell out what actually would happen, but that tax revenue goes to pay for Social Security and Medicare," Rothstein explained. "And so if you got rid of those taxes, or cut them, then that takes away the funding that finances Social Security benefits. And without new legislation, we would have to either come up with other money for it or we'd be cutting the funding for Social Security."

The silver lining here, though, is that the Constitution grants Congress power over spending federal funds, not the president. It is debatable whether the president can even issue the executive orders that he already did; he does not have the power to unilaterally make permanent changes to payroll taxes.

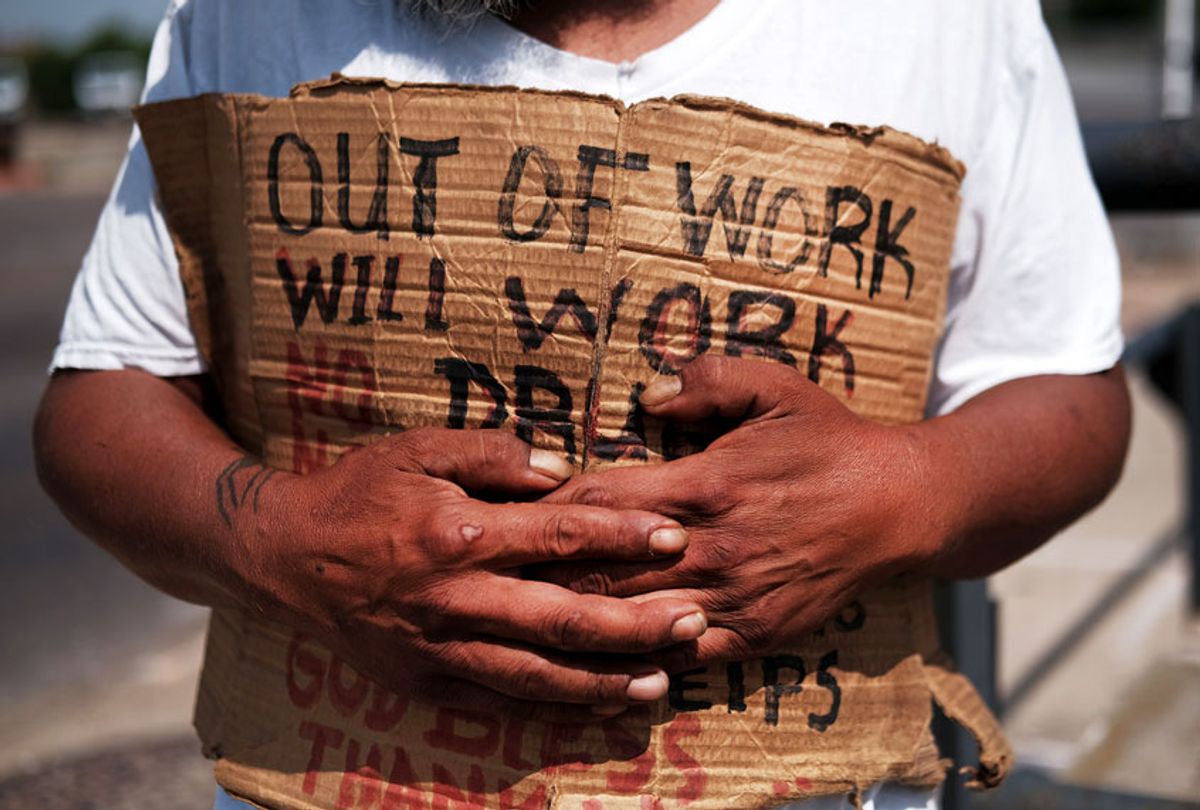

3. If you're surviving off of unemployment benefits, Trump's executive order just made your life a whole lot harder.

"The $400 unemployment extension is less than the $600 before [from the CARES Act], and it requires a 25% ($100) match from states so it may not even happen given how tight state budgets are," Mathy told Salon.

Dr. Betsey Stevenson, an economist at the University of Michigan, told Salon by email that "states are highly unlikely to come up with an extra $100, so the Department of Labor has already said that regular UI [unemployment insurance] payments can count toward it. If all 31 million people currently receiving UI get these payments, the pot of money that the administration has allocated for it will last only until the beginning of September."

Dr. Richard D. Wolff, professor emeritus of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, told Salon by email that there was no evidence that the $600 unemployment supplement was disincentivizing work to begin with.

Wolff added, "In [National Economic Council Director] Larry Kudlow's words, this is because $600 extra is a disincentive to work (for which no evidence exists that I know of or respect). In honest terms, the reduction is a measure aimed to force people back to work and thereby operates as an incentive for employers to cut likely wages or benefits knowing how many desperate recipients of $400 instead of $600 want/need almost any job."

Rothstein stressed to Salon that, as with much of Trump's Saturday executive orders, the exact ramifications are unclear because the new policies themselves are not well defined.

"it's completely unclear. This creates a new program out of scratch out of whole cloth, but the details have not been worked out," Rothstein explained.

4. This is not good news for the economy.

Both Mathy and Wolff agree that this is not long-term good news for the economy, which will need to put a lot of money in Americans' hands to prevent widespread poverty and maintain a sustainable level of consumer spending.

"It's better to keep these program going as the pandemic is continuing, but as these programs will almost certainly be cut back, this will make being unemployed harder — and with the government pumping less money into the economy, the recovery is likely to slow or reverse," Mathy explained.

Rothstein expressed a similar view, telling Salon that "people need this money. Our economy needs this money. Our economy needs people not to be going bankrupt due to the pandemic. We need people to be able to pay their rent and buy groceries It looks as if have we cut off the benefits they were depending on when there was no realistic prospect of them going back to work. That's bad for all of us."

Referring to the reduced unemployment package, Stevenson told Salon that "while this spending is better than no spending, it's a far cry from what is needed to stave off hardship and poverty. We currently have widespread unemployment, it is the reason why additional stimulus is so necessary."

Wolff said the executive orders were partially a distraction. "Trump needs to keep attention away from the [pandemic] and economic crunch," he said. "Breezy orders about relief are this week's deflection effort — not much likely real effect, mostly political theater."

Wolff said the way that Trump and his party were pandering to employers rather than workers was criminal. They are "savaging [the] working class back into unsafe working conditions," he said. "The risk they take (beside the utter immorality of it all) shows how desperate they are and how everything is aimed at the [November] election. A modern version of Louis XIV's 'apres moi le deluge.'" The translation for that: "After me, the flood."

Shares