If and when the Western world rids itself of the novel coronavirus, we will owe Dr. Katalin Karikó a great debt of gratitude. That's because Karikó, a Hungarian biochemist, helped pioneer the revolutionary vaccine technology behind the most prominent and effective novel coronavirus vaccines.

Even more astonishing is the fact that Karikó faced repeated professional rejection for championing the very ideas that are now saving lives.

Indeed, Karikó is one of the pioneers behind mRNA vaccines, a type of new vaccine technology for which many of the current crop of coronavirus vaccines rely upon. These types of vaccines involve the creation of a synthetic single strand of an RNA molecule known as messenger RNA (or mRNA). An mRNA vaccine injects a bespoke version of mRNA into the body. That mRNA then infects human cells and trains them to produce proteins like those found in a given virus.

Because the immune system will recognize those proteins as antigens, or a foreign substance that needs to be vanquished to protect the body's health, the mRNA vaccine ultimately trains the body to defeat a given pathogen (that is, a disease-causing agent) before it can inflict harm. It is analogous to the military having soldiers participate in realistic war games so they can be better prepared in case they have to enter actual combat.

This is different from conventional vaccines, which come in a few varieties: live-attenuated vaccines, which use a weakened form of the germ that causes a disease; protein subunit vaccines, which use materials that are neither living nor infectious but contain one or some of the antigens from the pathogen in question; and viral vector-based vaccines, which give a blueprint to cells of the pathogen they may need to fight rather than part of the pathogen itself.

Yet none of these are quite like mRNA vaccines. As illustrated by the rapidity with which mRNA vaccines for COVID-19 were developed, mRNA vaccines are generally capable of being manufactured in a comparatively shorter period of time. Thus, less than a year after SARS-CoV-2 caused a global pandemic, scientists at Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna were able to develop safe and effective vaccines.

Yet if Karikó's early critics had had their way, this technology might never have existed.

Karikó saw the potential in mRNA vaccines shortly after she joined the University of Pennsylvania's School of Medicine in 1989, according to The Guardian. Yet although she and her colleagues recognized its potential, they struggled mightily to get funding for their research. She filed grant request after grant request after grant request and was repeatedly rejected, with potential backers feeling her ideas were too novel or mistakenly believing the human body would not allow mRNA vaccines to work. In 1995, the University of Pennsylvania took her off of the path to full professorship and demoted her, a major career setback for a promising biochemist.

"I want young people to feel — if my example, because I was demoted, rejected, terminated, I was even subject for deportation one point — [that] if they just pursue their thing, my example helps them to wear rejection as a badge," Karikó, who today is a senior vice president at BioNTech RNA Pharmaceuticals, told Salon last month when discussing her story. "'Okay, well, I was rejected. I know. Katalin was rejected and still [succeeded] at the end.' So if it helps them, then it helps them."

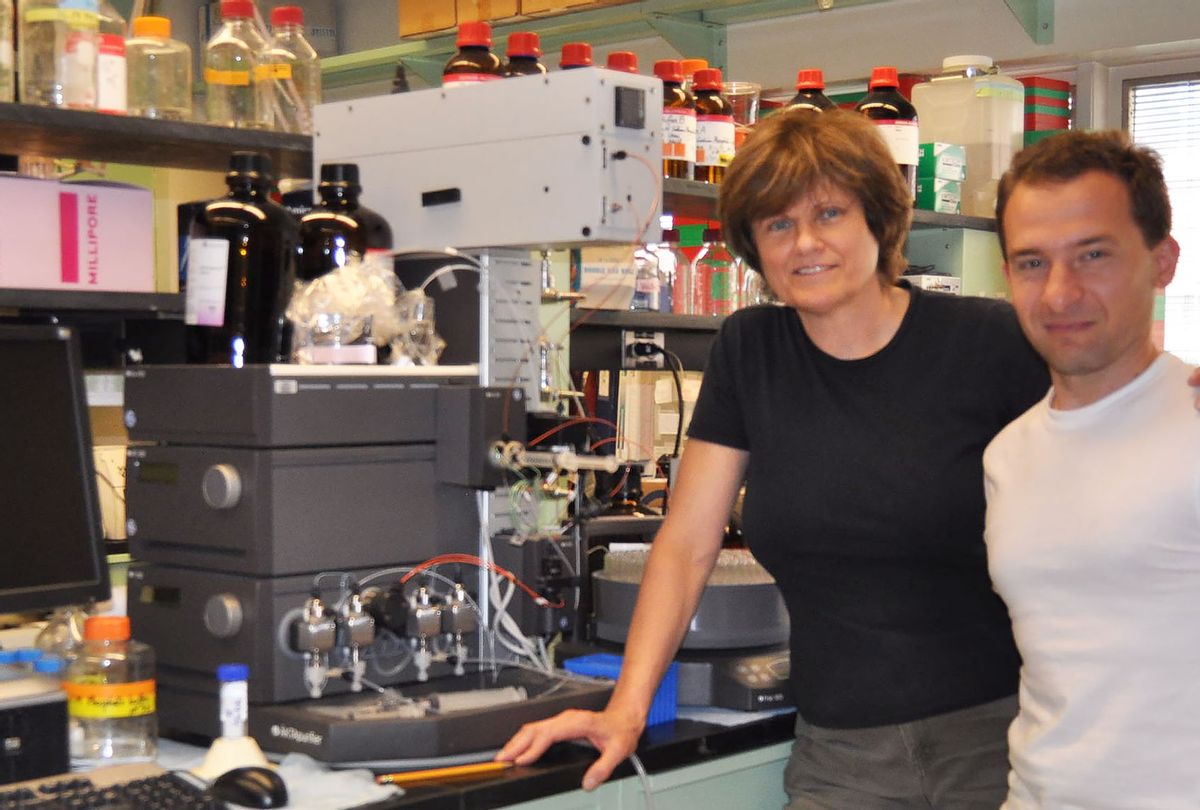

Despite her demotion, Karikó continued with her work and, along with a fellow immunologist named Dr. Drew Weissman, penned a series of influential articles starting in 2005. These articles argued that mRNA vaccines would not be neutralized by the human immune system as long as there were specific modifications to nucleosides, a compound commonly found in RNA.

By 2013, Karikó's work had sufficiently impressed experts that she left the University of Pennsylvania for BioNTech RNA Pharmaceuticals.

Karikó tells Salon that the experience taught her one important lesson: In life there will be people who, for various reasons, will try to hold you back, and you can't let them get you down.

"People that are in power, they can help you or block you," Karikó told Salon. "And sometimes people select to make your life miserable. And now they cannot be happy with me because now they know that, 'Oh, you know, we had the confrontation and...' But I don't spend too much time on these things."

She also offered advice for aspiring young scientists who wonder whether they can pull off the necessary work-life balance to achieve their goals, as Karikó often worked so hard in the early stages of her career that she would sometimes spend months working every day and even sleep in her office. Karikó ventures that it is possible — and worth it.

Obviously, everything worked out for Karikó in the end: besides helping the world beat a historic pandemic, some of her professional peers believe she is going to be awarded for her years and years of work on mRNA vaccines. As Dr. Derrick Rossi, who helped found Moderna, told STAT News, Karikó and her colleague Weissman both deserve the Nobel Prize in chemistry. "If anyone asks me whom to vote for some day down the line, I would put them front and center," Rossi said. "That fundamental discovery is going to go into medicines that help the world."

Shares