Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell doesn’t seem to know whether he’s coming or going these days. One minute he’s condemning Georgia Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene as “a cancer” on the Republican party and the next he’s voting with the majority of GOP senators to reject the idea that Greene’s mentor, Donald Trump, can constitutionally be impeached and convicted for inciting a violent riot. McConnell now appears uncharacteristically unsteady, unsure how to proceed in a world in which his party has become so radicalized that average Republican voters are capable of storming the Capitol and demanding the execution of a stalwart conservative and Trump loyalist like former Vice President Mike Pence.

He shouldn’t be surprised by any of this, however.

The GOP’s intensifying radicalization has been building for a very long time and McConnell and the rest of the establishment adopted a “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil” stance because they benefited from the energy, dedication and money they received from the ever more crazy Republican grassroots. The Washington Post’s Greg Sargent observed that this actually goes all the way back to the early post-WWII years, drawing on the work of political scientists Daniel Schlozman and Sam Rosenfeld’s authors of “The Long New Right,” who say that the right’s addiction to the “politics of conflict” has always made any wall between the extremists and establishment fairly porous. Sargent points to the back and forth between the mainstream and the John Birch Society in the 1960s, flirtations with the Ku Klux Klan and “Newt Gingrich’s conversion of GOP politics into nationalized scorched earth warfare,” the latter of which was the first step to openly marrying extremist rhetoric and tactics to the party itself.

Norm Ornstein, who has written a number of books on the radicalization of the modern GOP noted recently that it was Gingrich who turned the Republican Party into a cult, saying Gingrich “very deliberately generated tribalism” creating a “situation where people could view Democrats as evil, trying to destroy their way of life.” Of course, it wasn’t just Gingrich. He came to prominence at the same time that talk radio became a toxic hatefest creating star propagandists like Rush Limbaugh. Roger Ailes then joined up with Rupert Murdoch to create a TV and print empire to similarly stoke the partisan acrimony. The Clinton years were a dumpster fire of partisan rancor.

The GOP establishment was fine with that, of course. By the time the Bush administration came along, their base was well primed and the media infrastructure solid. The Republican leaders of the Bush-era may not have been as bombastic as Gingrich or Trump but they played a major part in radicalizing the Republican party as well. If you want to talk about Big Lies, look no further than “Saddam had WMDs” and “Saddam was involved in 9/11” for a couple of propaganda success stories. Years later, former Vice President Dick Cheney unsuccessfully tried to wriggle out of it, but of course, it had already gotten the job done and they had moved on to their favorite enemy: Democrats.

After Barack Obama took office in the midst of an economic catastrophe, the big money funders were on hand to help and the Tea Party was born. They ratcheted up partisan hysteria over President Obama’s health care proposal, giving their activist base something tangible to do by instructing them to storm town hall meetings and disrupt the proceedings. They were even known to hang and tar and feather lawmakers in effigy, even converging on the Capitol to get in the faces of a group of Democratic congressmen, screaming the “n” word, spitting at them and taunting an openly gay representative.

The GOP establishment said not a word and they won the 2010 midterms that year in a landslide. Imagine that.

Among their new members was a group of far-right extremists who formed themselves into the Tea Party-aligned House Freedom Caucus, who believed in using the same confrontational tactics with legislation as the Tea Party activists. There was no longer any such thing as compromise or negotiation. It was “my way or the highway” with the Democrats and if the Republican leadership didn’t like it, well, that was too bad.

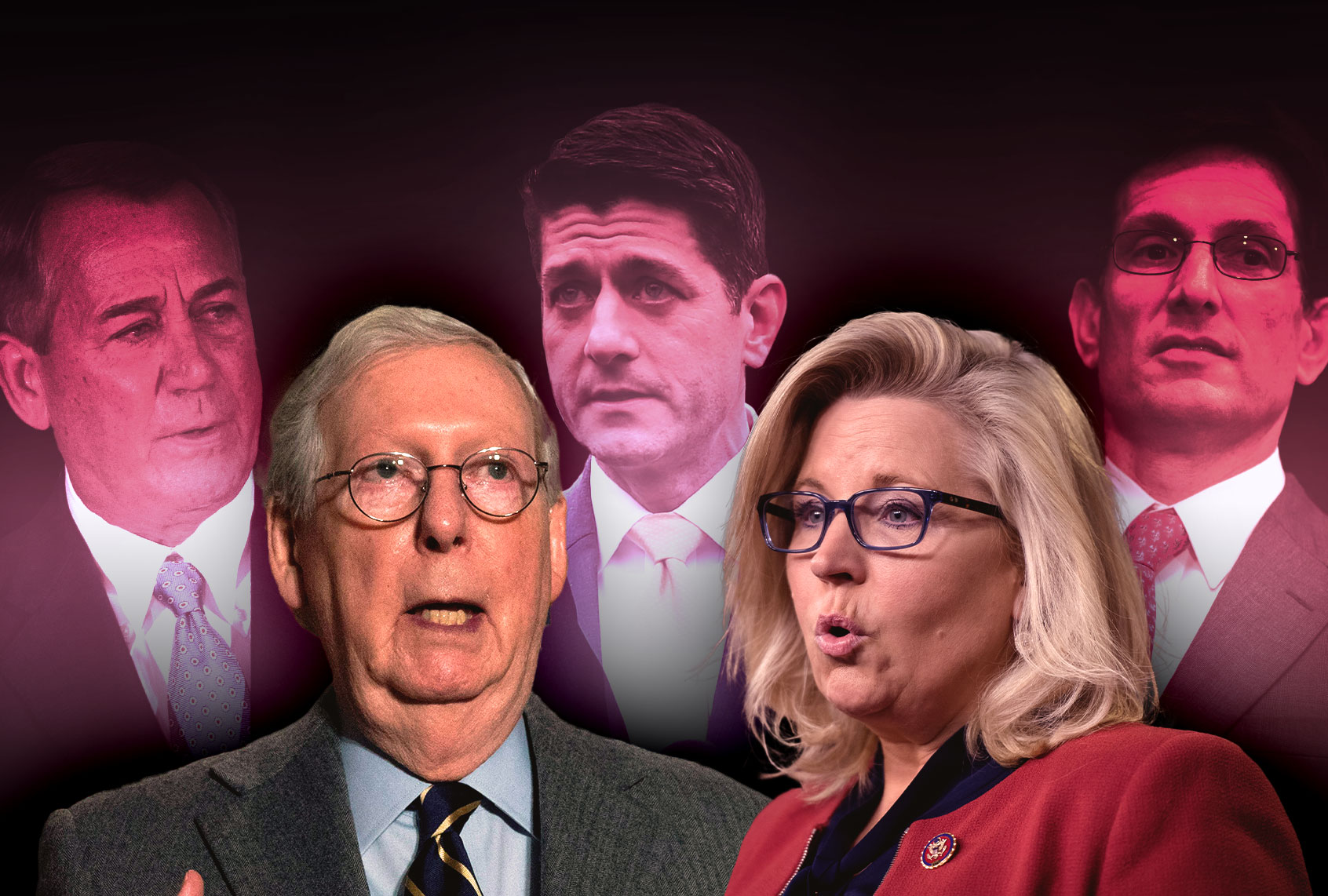

By 2014, they were gleefully devouring their own. In a shot heard round the beltway, a Tea Party candidate backed by right-wing radio took on the House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, R-Va., in a primary, and beat him. Cantor’s sin? He had strayed from the orthodoxy very slightly on immigration, which was bubbling up (again) on the right as a central issue. Soon, Speaker of the House John Boehner, R-OH, was forced out as well, replaced by Wisconsin dreamboat Paul Ryan. By the time Donald Trump came along in 2015, Ryan too was already in their crosshairs.

Trump watched all of this and in his instinctual, feral way, understood exactly what the Republican party base had become. He didn’t create the cult. It already existed. He just took it over.

For the past 30 years, the Republican establishment has either guided or accepted every step of their party’s descent into extremism. And no one has been more willing to make that deal with the devil than Mitch McConnell. In fact, he made one of the greatest contributions to the radicalism of the GOP by exploding one Senate norm after another and turning the filibuster into a partisan weapon.

Now he’s facing a big problem.

January 6th laid bare just how fanatical and downright seditious the Republican base has become. He’s lost his majority and has several vulnerable members up for re-election in 2022. They are going to have a hard time winning statewide if 25% of their voters reject the Republican party because it’s turned the asylum over to the inmates. He’s greatly worried about corporate America’s revulsion at his party’s behavior and their unwillingness to finance it going forward. Seeing a so-called moderate senator from Ohio, Rob Portman, cutting and running has to hurt.

House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, on the other hand, is caught between a deep desire to please Donald Trump and a competing desire to please his corporate donors. He’s handling his dilemma even less gracefully than McConnell. It’s anyone’s guess what will happen in the fight between Liz Cheney of Wyoming and the faction backing the Trump worshiping conspiracy monger from Georgia, Marjorie Taylor Greene, but the mere fact that such a battle is even happening is testament to the fact that McCarthy has no control over his caucus. I’m sure John Boehner is chuckling mordantly at the thought of his former Freedom Caucus nemesis’ little dilemma as he sips his glass of Merlot on the back nine.

McCarthy also has to be thinking about what happened to Eric Cantor just six years ago. At one time the two of them, along with Paul Ryan, were feted in the GOP as the so-called Young Guns, the new generation of GOP leadership. But the rabble rousing Tea Party candidate who took Cantor’s seat was ousted by a Democrat, Abigail Spanberger, in 2018 and she held on to it in 2020, against all odds. McCarthy is now getting some blowback from Trump voters in his conservative district for failing to show undying fealty to the former president. It’s unlikely his district would go Democratic — but in California’s jungle primaries you just never know what might happen.

The radical chickens have come home to roost and they have taken over the place. The Republican establishment turned a blind eye to right-wing extremism for decades and now it’s come to define the Republican Party. They have no one to blame but themselves.