There's been considerable chatter over the past few years about the crisis of democracy — sometimes more clinically described as a "democratic recession" or "democratic deficit." And for good reason: When Donald Trump stripped the flesh off the American body politic, he revealed a disease that has become endemic throughout the so-called Western world.

Faith in the power and goodness of democratic self-governance, previously as unchallenged and ubiquitous as belief in God during the Middle Ages, has decayed into the empty, hopeful rituals of the Anglican Church. Even those who insist they still believe are clearly troubled: Supposedly democratic elections are too often won by overtly anti-democratic or authoritarian leaders, and too often result in governments that ignore what the public actually wants and pursue policies that blatantly favor the rich and powerful and make inequality worse. (As, in fairness, nearly all governments tend to do.)

But the important question is not whether this is happening — the answer is obvious — but why. Trump and Vladimir Putin and Viktor Orbán and Jair Bolsonaro and Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Rodrigo Duterte and all the other pseudo-democratic usurpers around the world didn't arise out of nothing. To suggest that they all simultaneously tapped into a current of know-nothing darkness and bigotry and moral weakness that has been there under the surface of society all along, like undiscovered crude oil, is not a remotely adequate historical or political explanation.

To see so many marginal democracies tumble into the abyss — and a great many well-established ones tiptoe right to the edge — suggests that something else is going on, a deeper pattern we aren't ready or willing to look at. That deeper pattern isn't just a crisis of democracy in the narrow sense, meaning a system or mechanism for selecting hypothetically representative leaders, because that itself is a symptom or symbol. It's about the failure of liberalism, which is an especially confusing word in the American context but in larger historical and philosophical terms describes the amorphous and often contradictory set of beliefs that supports democracy — and without which democracy becomes impossible or meaningless.

Liberalism, in that broader sense, has dominated an increasing proportion of the world since the early 20th century and virtually the whole planet since the end of the Cold War. It's a tradition that included (until very recently) both the conventional left and the conventional right in the United States and most other Western-style democratic nations. It's not so much a coherent philosophy as a basket of principles, many of which are frequently in conflict: Free trade and the primacy of the capitalist "free market," the expansion of civil rights and civil liberties, freedom of the press and artistic expression, universal equality before the law and a contested role for the state, which is sometimes highly interventionist and sometimes much more hands-off.

To put it mildly, there's been a lot of disagreement within the liberal tradition about which of those principles is most important. Old-school "classical liberals," for example, eventually became known as conservatives or libertarians, while the "new liberals" divided into camps most often described today as moderates and progressives. In the wake of World War II and then the Cold War, liberalism writ large began to imagine itself as the end stage of human history, promising a world — in the infamous (and false) words of Thomas Friedman — in which no two countries with McDonald's franchises would ever go to war.

But as two important recent books about the liberal tradition — Pankaj Mishra's "Bland Radicals" and Louis Menand's "The Free World" — argue in different ways, that confidence was hubristic, and liberalism had already undermined itself at its moment of apparent total victory. The most generous thing we can say is that liberalism sometimes delivered on some of its promises (and only to some people), but never came close to fulfilling all of them. As for the liberal tradition's willingness to accommodate heated internal debate, as well as to wrestle with its own errors and blind spots, that was seen (with some justice) as a defining virtue — and was also, from the beginning, a critical weakness.

Most of the invigorating essays in Mishra's collection revolve around the insight that the disastrous failures of liberal foreign policy — so vividly illustrated in Afghanistan over the last few weeks — cannot be understood as aberrations or even contradictions. From the beginning, the liberal promise of expansive civil rights and ever-increasing prosperity (for the citizens of liberal nations) relied on overseas imperialism and ruthless exploitation, what we might today call the outsourcing of inequality. Furthermore, imposing Western-style liberal democracy on other nations (who were understandably uncertain it was a good idea) — through coercion and bribery and outright force, if necessary — was built into the model all along, even if that became embarrassing in the 20th century and had to be described with euphemisms about "freedom" and "self-government."

Menand's book is a sprawling, ambitious study of Western (and mostly American) culture during the Cold War years — from the avant-garde to Elvis Presley, from academic literary criticism to "The Feminine Mystique" — which could fairly be described as the greatest accomplishment of the liberal era. One of the central threads running through his history is the way this amazing cultural explosion began to pull the postwar liberal consensus apart, such that by the end of the Vietnam War, most American writers, artists and intellectuals saw themselves as enemies (or at least critics) of the American state, especially in terms of its global-superpower role.

In other words, while the crisis of electoral democracy seems to have appeared suddenly in the Euro-American backyard over the last 5 to 10 years, like a nasty invasive weed — and is still viewed by many observers as an almost inexplicable phenomenon — the implosion of the liberal order has been a long time coming. It's hard to see that clearly through the ideological haze, given that the media and political classes in the U.S. and most other Western nations (outside the far right and far left) remain steeped in a post-World War II worldview where some version of liberalism — however much amended, repaired and clarified — is the natural, inevitable and desirable order of things.

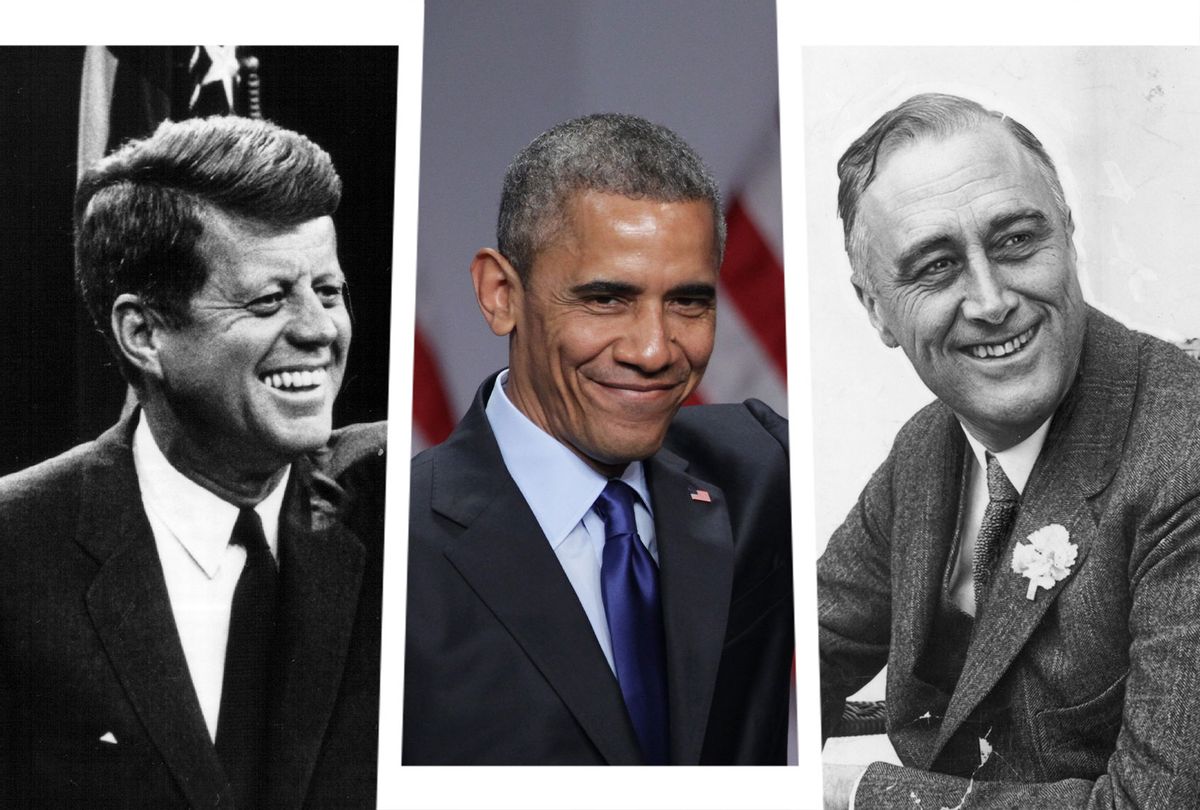

If liberalism remains the only paradigm available to resist the rise of Trump-style autocracy, as generally seems to be the case, then we're in deep trouble, and the dread so many of us feel about the inexorable erosion of democracy is fully justified. Does anyone today — literally anyone — possess the kind of universalist, upward-trending faith in liberal progress that drove the mythology of John F. Kennedy's brief presidency or the moral clarity of the civil rights movement?

In bizarre, upside-down fashion, Donald Trump's entire "Make America Great Again" campaign can be understood as a half-conscious attempt to rekindle that kind of collective passion, if only as ghoulish racist parody — the liberal soul, transplanted to a fascist body. (Trump's most insane followers in the QAnon cult briefly convinced themselves that John F. Kennedy Jr. was still alive and would return as Trump's running mate or spirit animal or something.)

Only someone with a time machine could tell us whether it will be possible to redeem or renew the better aspects of the liberal tradition as a vibrant force against the rising tide of jingoism, tribalism and autocracy. What we can say right now is that every few years someone emerges on the world stage who is embraced by the media and political caste as the savior of liberalism — or, worse yet, as the "transformational figure" who will overcome political paralysis and division — and it never ends well. No doubt Bill Clinton and Tony Blair think it's profoundly unfair that they have been consigned to the dustbin of history just because they made catastrophic compromises with the forces of evil. Emmanuel Macron actually believed he could make friends with Donald Trump, and that hubris may also pave the way for the far right's return to power in France, for the first time since the Nazi occupation.

Let's consider the most famous example, whose lessons "liberal" Americans (in all senses of the word) have not yet begun to understand. In the United States we have told ourselves a more sophisticated version of the above-mentioned narrative about how the current of ignorance and darkness running beneath our society has endangered democracy. It possesses some historical plausibility and, almost by accident, is a little bit true. In that story, the election of Barack Obama — which seemed to inaugurate a new era in American history and to symbolize a fulfillment of America's democratic promise — triggered the benighted racists in flyover country so badly that they all flocked to the banner of a TV con man who ran for president on a platform of blatant white-supremacist fantasy.

There's something to that, as public opinion research makes clear: Overt racial hostility is the decisive marker between white people who voted for Trump and white people who didn't. But to view that as a linear, limited cause-and-effect equation is the most mechanical and ahistorical kind of pop psychology, not to mention massively condescending. Like nearly all political analysis in our perishing republic, it's focused on symbols and signifiers, and not at all on the actual substance of politics. Obama himself would surely tell you that if his presidency had been successful, it would not have provoked such intense antipathy among many working-class and middle-class white people in the heartland — groups among which he did reasonably well in the 2008 election.

Obama came to office hoping to put an end to the era of red-blue political division and change the terms of American public discourse. Even his extensive post-presidential fanbase doesn't talk about that too much now, because it makes his entire project sound hilarious and doomed, like King Canute trying to hold back the tide. His utter and complete failure to do those things — like all other failures of all other liberal politicians — usually gets blamed on Republican intransigence, entrenched public prejudice or his own lack of Beltway backroom negotiating prowess. (Or just on Joe Lieberman.)

Biographers and political historians will chew on those factors for decades, no doubt. But to suggest that if this or that tactical or strategic decision had been made differently the Obama presidency might have had a different outcome — and a less gruesome aftermath — is to deliberately miss the deeper and more uncomfortable lesson.

Barack Obama was the most charismatic and eloquent political leader most of us will ever see. He won a landslide election (over a widely respected conservative war hero) as the last great defender of liberalism. His presidency failed because he was the last great defender of liberalism — maybe, in retrospect, something like the Mikhail Gorbachev of liberalism —not because Mitch McConnell was mean to him or because Revolutionary War cosplayers terrorized members of Obama's party into pretending they didn't even know him. Or rather, all those things amount to the same thing: Obama believed he could make us believe in the promise of liberalism again, but he couldn't because we don't, and because none of these golden-boy savior-hero types can ever do that. He tried and we tried, and it was a nicer exercise in nostalgia than the one that came afterward. So at least there's that.

Shares