"Some diseases are immutable facts," says Suzanne O'Sullivan. But from there, it gets complicated.

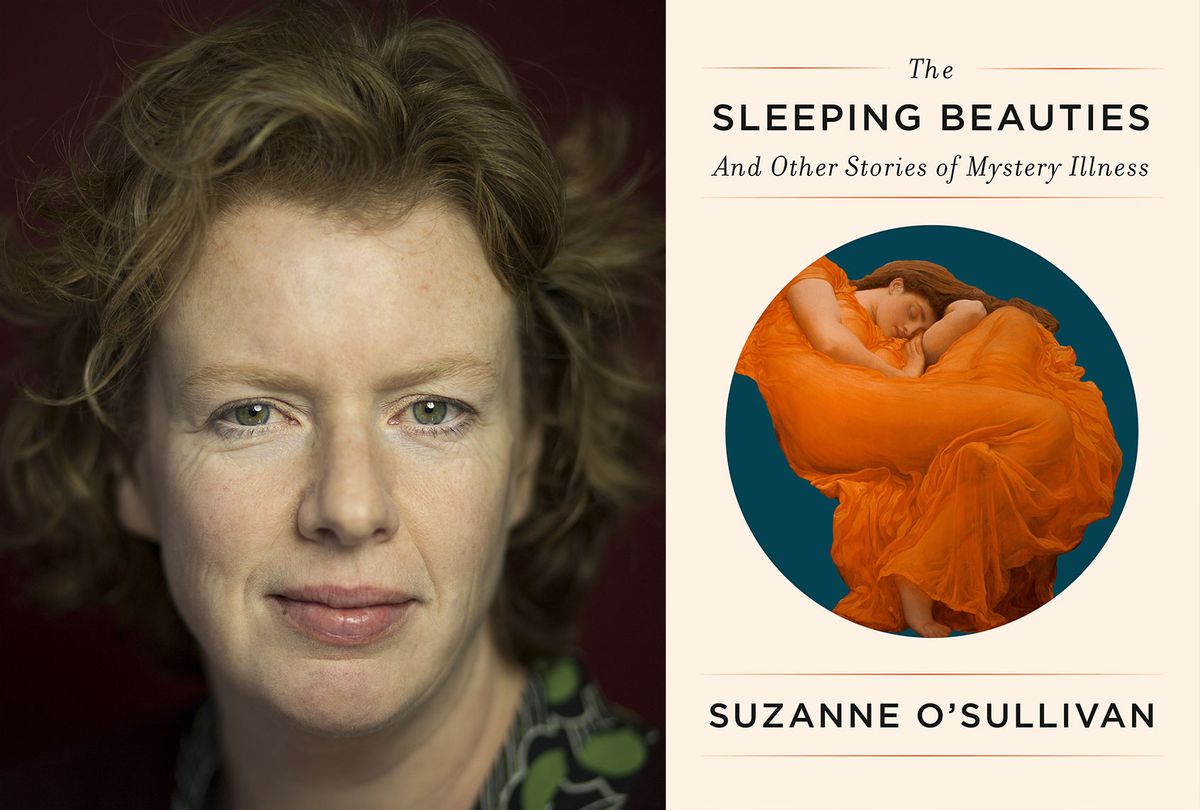

The Irish neurologist has spent a good portion of her career exploring the confounding and often controversial terrain of physical symptoms that seem to defy explanation. In her previous book, "Is It All in Your Head? True Stories of Imaginary Illness" she looked at psychosomatic illness through the lens of individual cases. Now, in the fascinating follow-up, "The Sleeping Beauties: And Other Stories of Mystery Illness," O'Sullivan travels around the world to explore mass cases. From a group of near-catatonic refugee children in Sweden to an upstate New York town besieged by a media-labeled "mass hysteria," O'Sullivan looks at the political, social and cultural contexts of these apparent "outbreaks," and asks what we can learn from them about how we talk about illness.

During a recent Zoom chat, Salon spoke to O'Sullivan about the liminal enigma of the mind and body connection, and why getting a diagnosis is vastly different from truly understanding — and treating — what's going on inside. As always, this conversation has been lightly edited and condensed for print.

Tell me first, what is a psychosomatic illness, and what does that term mean? There's a lot of stigma and confusion and apprehension around giving certain symptoms or conditions that designation.

Labels and names are a real problem here, because we all mean different things by them. Psychosomatic disorders traditionally defined as real physical symptoms that are thought to have a psychological cause, or at the very least, are not known to have an organic cause.

A lot of people have the sense that "psychosomatic" means that every symptom must be due to psychological distress or this Freudian idea that it all dates back to a single moment of horrible trauma in your life or to your childhood. I certainly, when I use it, do not mean it in that way.

I'm talking about physical symptoms that arise because of some sort of glitch in the cognitive processes that make up the mind, and that can sometimes occur through trauma and childhood things, but can also happen for hundreds of other reasons. I'm not talking about, necessarily, stress or psychological trauma-induced symptoms, but rather, symptoms that arise mostly in the cognitive processes of the mind. I think most people now dispense with "psychosomatic" because it's so prone to being misunderstood.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

There's a misunderstanding that it means it's, quote-unquote, "all in your head."

Precisely, or that you're making it up. Even worse, that you're making it up or that you're faking it. The point about psychosomatic conditions is they are biological conditions, like anything else. If you have a symptom that shouldn't be there, if you have a disability that shouldn't be there, it's biological. The distinction we make between a psychosomatic disorder, due to real biological changes, and a disease, is due to pathological. So psychosomatic conditions arise out of physiological changes and diseases arise out of a pathological changes.

That gets complicated because there is a sense, certainly in the Western world, that there has to be a very clear-cut designation between something as physical or as psychological. There's very little space in between. Yet you found things that dispute this. There's a phrase you used, that the presence or absence of disease are not immutable ideas.

Some diseases are immutable facts. If you have diabetes, if no one ever finds out, or if no one ever measures it, you will still get sick with it. Some diseases are facts and, at present, you don't have to describe them or name them for them to have an effect.

Illnesses are different. Illnesses are, to a certain degree, cultural constructs. An illness is a perception of how one feels. And to a certain degree, around the edges of illness in particular, your society and your culture tells you what is an illness and what is not. If we use the example of depression, some cultures would consider depression not a medical disorder, but a situational phenomenon. In Western medical cultures, we might be more inclined to label someone as having a brain-related problem causing depression, or we will equate depression with hormonal or with neuro chemical changes in the brain, for example, whereas another community might prefer to consider it situational.

I feel that in Western medicine, we think because we write all these things down in big books and give them technical names, that we have superiority in that, of medicalizing bodily changes. It's very difficult for a doctor to say when high blood pressure becomes pathological. Obviously, high blood pressure is a disease, dangerous, needs to be treated. But in a room somewhere, a group of doctors are deciding whether you have normal blood pressure or high blood pressure and they're picking the number — not arbitrarily, but a little bit arbitrarily.

If that's what they have to do with diseases like high blood pressure or kidney disease or osteoporosis, imagine how hard that is to do in the field of mental health sciences, to decide what behavior we're willing to accept as normal, what behavior we think is too much and we're going to give a disease name to. I fear that in cultures that rely on Western medicine, we're pushed very strongly in the direction of over-diagnosing disease, for many social cultural, practical reasons. I'm not sure that we are superior to other cultures in the way we deal with mental health problems.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

There are a couple of things that I think of when you talk about that. One of that is over-diagnosis can lead to over-prescribing, medicalizing. And then what happens, in particular, to our younger and more vulnerable?

Much is said about pharmaceutical industries and over-prescribing and people making money out of illness. I suppose I'm worried about something that people talk about a lot less, and that's the way that people embody disease labels when you give them to them.

If we decide that something has passed from being within acceptable, normal limits into being a medical problem that deserves the attention of a doctor, then a person becomes a patient. And what do they do? They begin looking for other features of the label that they have been given. People can begin to then take on features of that label by searching for them. Our bodies are a mass of change and white noise, and we all have good days and bad days. If we're given a label through which we can explain these things, we can begin accumulating new symptoms by paying extra attention to our bodies.

I'm a neurologist, I run straightforward clinics for things like epilepsy, brain diseases. But a huge number of people who come to see me will have what would have once been called hysterical seizures, now are called dissociative seizures, but they're psychosomatic.

What's happened to these people is something like, for example, they're on a very busy train and they faint. What happens in a lot of faints is people shake. The other thing that happens in faints is that someone nearby is a first-aider, and says you had a seizure. Suddenly this young person has been told they had a seizure on the train, then they go to a casualty department for a very junior doctor who doesn't know anything about seizures, tells them they think they have epilepsy. Then what happens before they make it to my epilepsy clinic is that they begin embodying the epilepsy diagnosis by looking on the internet, to see what else is associated with epilepsy, by joining communities who are affected by this. They begin with one symptom, which is dizziness and collapse on the train, and they've accumulated ten more symptoms by the time they get to my clinic.

I'm not saying everyone does this. This is just something that some people do. And it' effect of labeling is that we embody the identity of that diagnosis and take on new features, which can lead us into chronic disability. I think people don't realize how dangerous labeling can be.

Let's get into this. For instance, let's say you are a woman and you have pain within a medical system in the West that doesn't understand women's pain, doesn't take it seriously, or then immediately says that it's psychiatric. We can see how this culture, then, of people who are eager to create a diagnosis and then eager to, well-meaning or not, exploit that can arise.

I think people like to blame pharmaceutical industries, but we should all be looking a bit at ourselves — me as a doctor, but also me as a patient, because a successful consultation for me is one where the patient leaves with a diagnosis, with a treatment and they're delighted with exactly what I've offered them.

A difficult consultation is one where you have to say, "Well, I don't think this is actually necessarily a medical problem." People like to be told a specific diagnosis so that they have information that allows them to know about prognosis and where they should go for help. It's easier for me to give a diagnosis. So we've entered into this collusion between patient and doctor where it is in everybody's favor to label things. Unfortunately that has long-term consequences that we don't properly think through.

When you have an answer, you have a path forward, you have a potential remedy, as opposed to, "Maybe I can work on my symptoms without ever getting a diagnosis."

It's important for me to say that I'm probably more than anything here talking about the fringes of some of these diagnoses. I want people with severe depression to get a diagnosis of depression, get the appropriate treatment. I'm really talking about where it's all a bit more uncertain, and it's much easier for a doctor to over-diagnose and under-diagnose. No one can argue severe depression is extremely serious and needs medical help. But it's in that very borderline area, over-diagnosing depression can have long-term implications for a person, first in the embodiment of the identity of being a depressed person. It'll never leave your records and it will never probably leave your unconscious identity, either.

One of the things that you were speaking to in this book that I think is important, is this idea of, instead of just embodying a diagnosis as a permanent state, can we think of some of these things as transitory?

I don't want to be depriving people of help. That's what we use labels for, is we use them to help, so people know where to go to for help. What we should be able to do is to develop strategies for helping people that don't require us to give people chronic disease labels. It should be possible for someone who's depressed or feeling very low, without being told that they're depressed, to have a place to go where they can talk and get support without necessarily needing the label.

Again, this doesn't apply to everyone. Some people are greatly helped by understanding the biology of what's happening to them and getting a disease label. But there is undoubtedly a segment of people who are made worse by being given a chronic disease label.

I think in Western societies, where we're very individualistic. We're expected to support ourselves, we don't live in big family groups like other cultures, we're less spiritual than we used to be, people are less inclined to turn to a spiritual leader for help. Again, I'm not advocating that these are the right ways, there's no right way or wrong way. But one caring institution that's always there is your doctor. If they are our caring institutions and we have to have a disease label to be allowed to go there, then this is what happens. There should really be methods of caring for people and giving them support that doesn't require us to give them chronic disease labels. Because unfortunately I think medicalization is not always very good for people's identities.

Looking at this book, you explore these serious physical manifestations of intense experiences happening across the world and how differently they are looked at and approached. What do you wish that doctors in the West knew about what you've seen traveling around the world?

One of the conditions that I came across that I just thought, really found very inspiring, was a condition called Grisi Siknis. This affects the Miskito People or indigenous people of the Mosquito Coast in Nicaragua. It doesn't exist anywhere else in the world, it's specific to this group of people. It manifests seizures and manic behavior; its literal translation is, crazy sickness.

People who exhibited these exact symptoms in the West would probably find themselves referred to a psychiatrist, which isn't necessarily a route that works for everyone with these symptoms. In fact, these symptoms only get better about 30% of the time in the West with psychiatry, 70% remain chronic.

But what happened within the Miskito Community is, developing these symptoms, there was a sophisticated language that said to the community, "I need help." What happened was that the community rallied round. If you had these symptoms in the UK or the US, you'd probably stay at home all day and you wouldn't want to be seen, and there'd be no community response. So this was a way for people to ask for help and to get community and support. Then there was a ritualized treatment involving a traditional healer. It was highly successful treatment, and it is understood by the Miskito Community that this disorder is caused by a demon or a bad spirit. The ritual drives away the bad spirit. I think a lot of Western people hearing that will say, "Oh, superstition," negative things like that.

Actually, when anthropologists and people who have lived in these communities have examined it more closely, they can see that it's, in fact, a highly, highly sophisticated, complex, problem-solving strategy used by the community. It's a way for young women to say that they need support and that they have a problem without having to be explicit about what the problem is. They're just able to ask for help without facing judgment, without having to be specific. It guarantees a nonjudgmental community response. That's beautiful, really, because they get better, whereas people with these sorts of problems in Western communities who are medicalized struggle to get better.

I don't know yet how to translate that into my own medical practice. I'm not a spiritual person, but I'm traveling around the world, meeting spiritual communities who are doing a great job of supporting each other and actually making people better. I have to consider how I can incorporate that into a scientific medical practice.

I think part of it is understanding the language of the symptoms. What is this person trying to say by expressing it in this way? What does this person want? And responding to the symptoms in that way, but also encouraging this idea of the community response, rather than shutting people away when something distressing and potentially strange is happening to them. I think there's something in the ritual to getting better, to be understood. It may be right for some people that we take a really Western medical approach of physiotherapies, psychological therapies, psychoanalysis, whatever it might be, a Western medical approach. It may be however that, for some people, we need to understand, communicate through the metaphor of their symptoms, figure out what it is they want and try and help them to get it.

What do you hope for the future of medicine?

What I hope is that it is possible for someone to ask for help without being categorized in a particular way.

I think it's particularly problematic in schools now because, it's very easy for a child to take on a label when they're in school. There are very many advantages to it, because people get help in exams or the school gets more funding or they get more teachers. It is very easy for us now to label our children who are struggling.

I would want a child to be able to say, "I'm finding it really difficult to get help," and we should be able to give the funding and give the help and support without giving the medical diagnosis. I'd really love to see us cutting down on our need to medicalize and biologize every human experience.

Shares