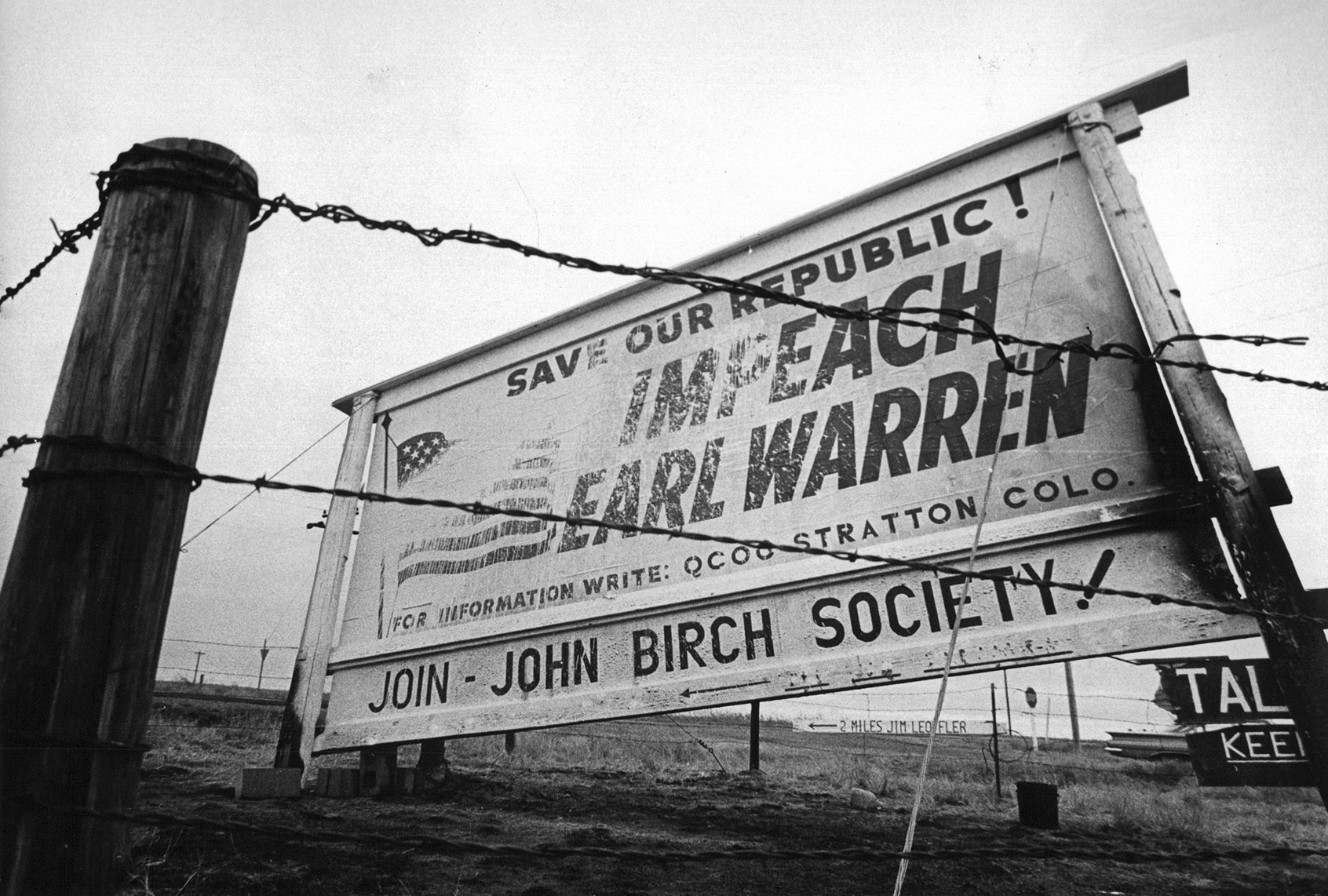

In the standard origin story of the modern U.S. right, today’s conservative movement was born with an excommunication: when William F. Buckley, the erudite, upper-crust founder of the National Review, turned on his onetime ally, Robert Welch of the John Birch Society, driving Welch and the rest of the conspiracy-hunting “Birchers” out of the respectable right. The truth, as always, is much messier, as historian and Northeastern University professor Edward H. Miller demonstrates in his new book, “A Conspiratorial Life: Robert Welch, the John Birch Society, and the Revolution of American Conservatism,” published this month by the University of Chicago Press.

“Like the fundamentalists of the 1920s, many Birchers did disengage when it became an embarrassment to be associated with the Society,” Miller writes. “Welch’s followers were seen as crackpots, deplorables, losers who did not fit into the modern world.” But rather than disappear, the Birchers just assumed a lower profile. And today, the ideas they promoted “are everywhere — even in the White House. Even in your own house.”

Miller’s book constitutes the first full-scale biography of Welch, which is surprising in and of itself, considering the impact the Birchers had on American politics, as the most successful anti-Communist organization in U.S. history. And it takes an impressively long view, beginning almost 200 years before Welch’s birth, on the North Carolina farms worked by his forebears — initially too poor to be slave-owners, and later on, consumed with elaborate paranoia about shadowy forces conspiring to take their human property away. Later still, as Welch grew up in the first decades of the 20th century — a child prodigy who became the University of North Carolina’s youngest student at age 12 —evidence of Southern farmers’ diminished status, and their fears of further “slippage,” was all around him.

RELATED: William F. Buckley and the Birchers: A myth, a history lesson and a moral

It doesn’t take much of a leap to see the resonance of that broad narrative today, or its psycho-political implications. Miller acknowledges this early on, writing that Donald Trump’s “entire political career — and a great deal of his popular appeal — lay in conspiracism of a kind that owes something to Robert Welch.”

But the deeper imperative of the book, Miller writes, is to correct historians’ long-standing misapprehensions about conservatism, and what the field has missed by dismissing the darker, stranger corners of the right, and how its apparent losers may have won the long game.

“For about two decades we have falsely bought into a narrative of American conservatism as a mild-mannered phenomenon,” with historical treatments of the New Right making “the tones of American conservatism sound like the Beach Boys,” argues Miller. In reality, “it has always sounded like death metal.”

Miller spoke with Salon this January.

How did we get here, and what does the answer to that question have to do with Robert Welch?

Well, a lot of the conspiratorial views he possessed are now reflected in the culture. He is primarily known as the individual who founded the John Birch Society and called Dwight Eisenhower a communist. He had other conspiratorial perspectives, arguing that schools, academia, the government, the media and other institutions of society were inundated with communists. And he had a conspiratorial view of history. He believed Sputnik was fake; that the Cuban Missile Crisis was exaggerated; that the 1952 election was rigged. He was a precursor to many of the issues that the “Reagan revolution” embraced, including abortion, anti-[Equal Rights Amendment] policy and tax reform.

What sparked the idea for this book?

I wrote a book called “Nut Country: Right-Wing Dallas and the Birth of the Southern Strategy,” and I just kept thinking that I’d missed something in the story of Robert Welch; that Welch was more important to what I was talking about than I’d mentioned. So it was basically a continuation of what I was doing with the first book, but at a new level, exploring the nuances of his conspiratorial style, his paranoid style, as Richard Hofstadter called it.

How have historians typically thought about Welch and the John Birch Society, and where did you feel a corrective was needed?

Typically the narrative has been promoted that was inaugurated by Lisa McGirr’s classic “Suburban Warriors“: that the John Birch Society was fringe, and not part of the respectable conservatism that gave way to the Reagan revolution. The John Birch Society wasn’t given the attention other organizations and individuals on the right, like William F. Buckley, were. But as things going on in the United States and around the world started to reflect some of the concerns the John Birch Society promulgated, I realized that this was not the correct narrative, and that we historians needed to look further at the intellectual losers of the far right: the surrealists, the individuals historians saw as charlatans outside the fringe.

Kimberly Phillips-Fein, a historian at NYU, says we have to start looking at the far right and considering its relationship with what’s considered “respectable conservatism.” I argue in the book that there really is no clear demarcation between the two — that “respectable conservatism” is influenced by the far right. And despite the narrative that Welch was ostracized from the conservative movement by Buckley, I argue in the book that he wasn’t, and his views were reflected in the views of Ronald Reagan in the 1970s and ’80s and continue to influence the right into the 21st century.

RELATED: Tucker Carlson’s Hungarian rhapsody: A far-right manifesto for waging the “demographic war”

I’m not alone. Historians John Huntington and Seth Cotlar have been hard at work making the case that we need to really look at the far right. David Austin Walsh has a book coming out in a few years. So my book is an attempt to look at one group that was the most important anti-communist organization to influence the far right and get a general audience to realize that the far right is more influential than we thought.

In discussing this myth that the Birchers were purged from conservatism, a couple of lines you wrote stood out to me: One, that the concept of the responsible right is a delusion; and two, that American conservatism sounds like death metal.

If we look at William F. Buckley, he said the 14th and 15th Amendments were “inorganic accretions” tacked on by the winners of the Civil War. He said we should never get rid of colonies in Africa until Africans “stop eating each other.” He says, in his letter to the South, that the white race is the advanced race at this particular moment in time. These are egregious things said by the “respectable” right. But he’s urbane, stylish, cosmopolitan, a member of the establishment.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Reagan continued to promote conspiracy theories throughout the 1970s. He was talking about how Gerald Ford was faking his own assassination attempts; in his campaign newsletter Reagan promoted a John Birch Society quack remedy for cancer called Laetrile. And his Iran-Contra policy was basically right out of the John Birch Society playbook: that the communists are taking over South and Central America. So I think it’s very clear that this “respectable” right has to be looked at again.

In terms of “death metal,” I guess I was having a little fun. “Suburban Warriors” is about Orange County, California. And when I read that it’s the story of upwardly mobile men and women in Southern California, I got the feeling that they were innocuous. No criticism of Lisa McGirr — it’s a pathbreaking book. But it’s a book that doesn’t focus enough on race and doesn’t focus enough on the strangeness of some of the things they were saying. I discovered “Suburban Warriors” during a graduate school colloquium, and as I read it, I said, this doesn’t sound like the conservatism I grew up with in Boston in the 1970s and early ’80s. This seems a lot more like the early Beach Boys. It really doesn’t show the darkness and the danger of some of the conspiratorial ideas that reverberated throughout the right.

Was Welch a victim of a paranoid time, or a leader who led other people into paranoia?

I think he sincerely believed. He was not anybody who presented these views for political or monetary gain. But there were unintended consequences of his political imagination that we see playing out. I do see him as a leader of that style, and really as the person that Hofstadter was homing in on. Hofstadter mentioned that it was a characteristic of American history. Welch was born in 1899, and I spent a lot of time on his family and their ownership of slaves and what it was like to live in the South at that particular time, with the fear of losing their slaves and this idea of a Northeastern establishment of bankers controlling them. That’s how they viewed the world. Welch is a sincere believer from this environment. But I don’t consider him a victim. He embraced this. He’s a very, very intelligent person who falls into this worldview.

I was interested in your description of Welch’s family’s sense of “slippage.” It’s almost impossible to read that without thinking of the wealth of stories we’ve seen about Trump voters, and their fear of losing status in a diversifying world.

I think it’s analogous. Honestly, Welch’s family was very lucky. They were doing very well. Welch himself did very well. I don’t think status anxiety applies to Welch individually. He was a very successful businessman. He had a loving family. He was surrounded by business leaders who revered him. He enjoyed white privilege. But at the same time, his family suffered some difficult times in the South after the Civil War, and there was a fear that things could fall apart. I never came across anything [from Welch] that’s exactly about those particular views. He was too optimistic about his future, I think, to suggest that. But definitely that connection can be made: that his family felt the same economic and social pressures that modern working-class folks feel in the deindustrialized Midwest.

RELATED: Who were the Jan. 6 attackers? Isolated white folks, searching for meaning — and enemies

You note several times in the book that we now live in Welch’s America.

Well, No. 1, conspiracy theories abound. There are conspiracy theories about vaccination policy and [vaccines’] alleged futility, despite the fact that these vaccines are saving lives. You can get into some of the strange things, like people who are using dirt to cure the coronavirus. At the same time, you have this belief that the [2020] election was rigged, despite all evidence to the contrary that suggests it was completely legitimate. Many of the conspiratorial views far-right media expounds would be something expressed by Welch back in his heyday. I mean, he doesn’t believe Sputnik exists. He believes the Cuban Missile Crisis, when the world came closest to nuclear annihilation, was exaggerated. He believes Vietnam was a phony war run by the Kremlin. He believes that the Korean War was run by the Kremlin. These are the kinds of things we’d hear today. Not necessarily the exact same things, but the unreality of it.

There are a number of places where that historical rhyming is so exact that it’s jarring: Welch belonged to an America First committee in World War II, while today we have a white nationalist movement called America First. Welch constantly depicted the civil rights movement as communist, just as today’s Black Lives Matter movement is called Marxist by right-wing media and politicians.

Well, here we are talking on Martin Luther King Day. Welch had a perspective that in Birmingham, when Bull Connor unleashed his dogs on African-American people fighting for justice, Welch came to the conclusion that what happened was one of the African-Americans hit one of the dogs and then it started to attack the crowd, and that’s where [reporters] came in and captured that picture. There’s no evidence whatsoever of that. That’s not what happened. It was Bull Connor who was attacking African-Americans and using fire hoses on people struggling for their civil rights. But it’s the same type of false flags you hear every day on the Alex Jones program, where there are communist agents provocateurs and no evidence to make that case.

If we continue to go down that line where we believe this nonsense, I think we’re going to be in a suboptimal position. Reality is very important and truth is very important. And if we’re going to continue to live in a country where we love one another, as Martin Luther King dreamed of, we have to have some agreement on what reality is.

Can you talk about Welch’s role in facilitating the presence of so much racism and antisemitism in movement conservatism?

As I mention in the book, it’s a complicated subject. There were contradictions, sophistry and duplicity in how he presented himself. He would denounce [America First Party founder] Gerald L.K. Smith, who was the most notorious antisemite, but at the same time, he would say that the parent of the communist conspiracy was the Zionist conspiracy. He would argue that some of his best friends were Jewish — and he did have a more amicable relationship with Jews, for his time, than Dwight Eisenhower — but he maintains relationships with some antisemites of the old guard. He kicked [white nationalist] Revilo Oliver — a fascinating palindrome — out of the John Birch Society, but he’s too slow to do so. I kind of agonized over this while writing; it was a complicated matter. But there never should have been antisemites in his organization. It’s inexcusable.

RELATED: “Blacks and Jews” authors: “Whoopi is not the enemy” but “it may be too late” for America anyway

In the final analysis, he could have done a better job to extirpate the vehement and notorious antisemitism that existed in the old guard. But I think William F. Buckley could have as well. Buckley had some of the same individuals in the National Review. So I think there’s a case that it’s not just Welch, it’s the institutional antisemitism that is part of both the new and the old right.

Were there points where you felt sympathy for Welch?

Some of the characterizations that were directed at Welch in the early 1960s were incorrect. There were individuals like Mike Newberry and [FDR’s son] John Aspinwall Roosevelt who called Welch a fascist and a Nazi. There were pictures of Welch next to [American Nazi Party founder] George Lincoln Rockwell. But those characterizations should have been handled with more nuance. And the idea that Welch was an authoritarian, there couldn’t be anyone further from that. He was not a charismatic speaker. He was a rather clumsy speaker. He would get up to deliver his speech, and it was kind of a disaster. His papers would be dropping. He looked like a professor. But they called him one goose-step away from fascism. And I just didn’t see anything in his personality, and in the John Birch Society’s response to that, that could substantiate those claims.

There was also so much infighting in the society. If you take a look at what early 1960s journalists and other authors wrote about him, they claimed that he would brook no insubordination. But the fact was he had to deal with too much of it, even from his own national council. He couldn’t get anybody to agree with what he was saying. Many people argued that he should just hand over the keys to the John Birch Society and somebody else should take over because of his conspiratorial screeds.

Are there figures today who play similar roles to those of Welch and Buckley?

I think it’s mirrored throughout the Republican Party. When [Sen.] Mike Lee says we live in a republic, not a democracy, those same points were made [by Welch]. There was a suggestion somewhere that fluoride should be outlawed. That was one of the pet projects of the John Birch Society. The goal of Steve Bannon to get [conservatives] on the PTA to address the vaccine — there have been disruptions in the middle of school board meetings because of this. There’s just so many. I read something and think, there we go again. The de-legitimacy of presidents. Welch suggested the Eisenhower presidency was illegitimate, that Ike stole the 1952 Republican primary from Robert Taft. We see the same effort to undermine Joe Biden’s presidency with the current shenanigans. I could go on and on. History doesn’t repeat itself, but it certainly rhymes, as you alluded to.

You write that Welch sincerely believed even his most ludicrous conspiracy theories. How does that compare today, in terms of people who sincerely believe conspiracy theories versus those who use them more cynically?

Robert Welch died with nothing. He spent all his money on fighting windmills. His wife had to sell their house [after his death] to survive. But today I think the temptation to make money off this is so powerful that many embrace this false reality for monetary gain. Welch wouldn’t and didn’t do that. It was completely different than something you’d see today, where people promote climate denial when they don’t believe it; when they’re taking the vaccines and the boosters while telling people it’s against their freedoms. I mean, it’s unconscionable. Sorry to get emotional, but I don’t know how they can sleep at night.

For people disturbed by living in Robert Welch’s America today, what can we learn from his story?

The more history we study, the more we realize that the actions of individuals create history. The idea that there is this grand conspiracy is false. The claim that everything is planned in advance is lazy and actually dangerous. We have to get beyond this nonsensical view of reality. There is a truth that we can get to and we have to make that commitment, and that involves some effort.