Depending on how you count, there have been at least 27 gun violence incidents in or near American schools in 2022; beyond those, there have been over 200 mass shootings at community events in the United States this year.

And it’s only May.

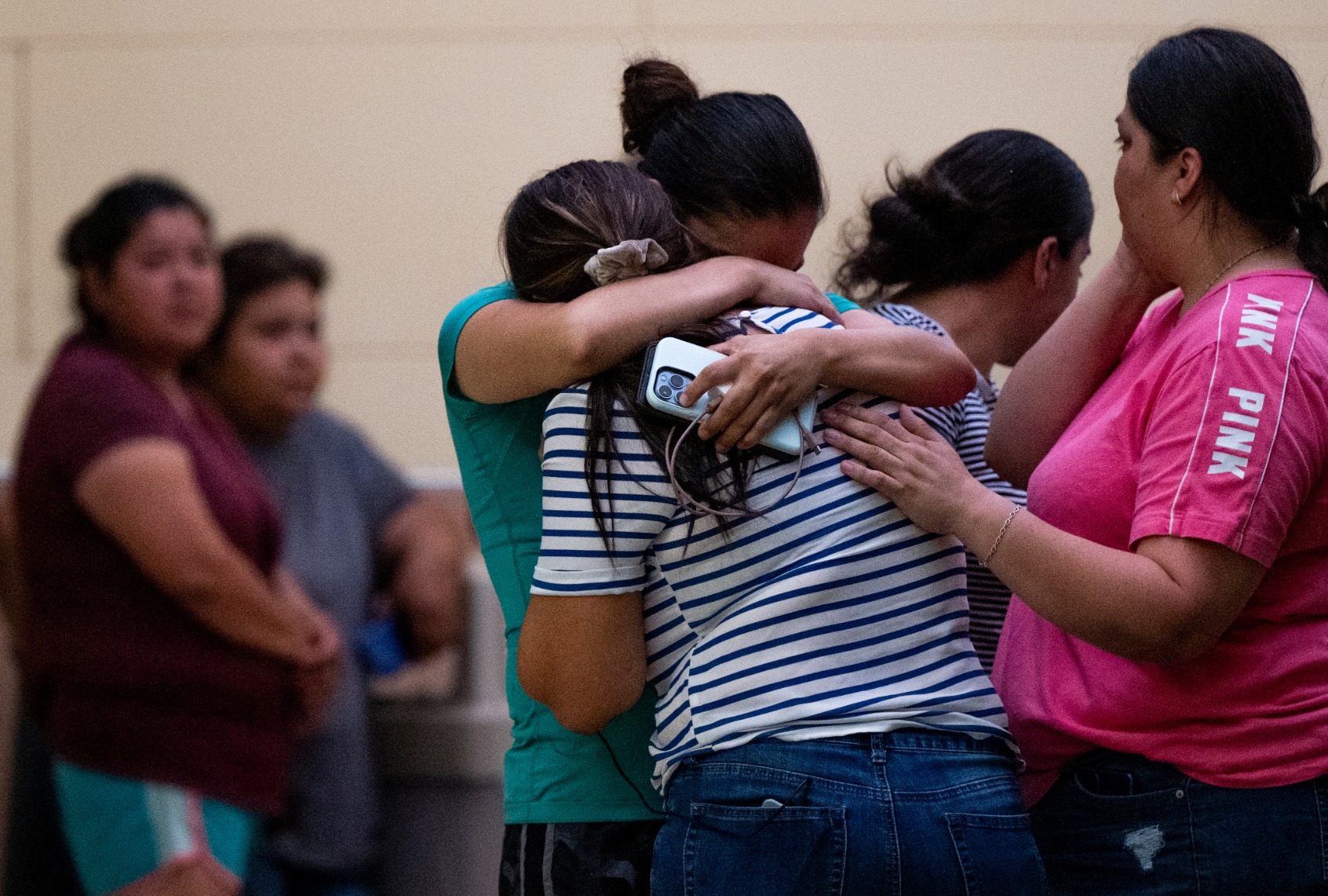

Every time a shooting occurs, all of scramble for news. We are overloaded and stressed consuming these images and videos online. And as painful as it is to process, we often feel helpless to do anything, and get stuck in a vicious cycle of doom-scrolling.

While expert definitions may vary, a mass shooting event is typically defined as a gun violence incident where four or more individuals are killed due to gun violence. Some definitions count those who were injured and/or close-range witnesses to gun violence. We know gun violence incidents have increased significantly in the past half-century: 45,222 people died of gun violence in 2020, the highest number since recording began in 1968.

“Gun violence and gun mass casualty events feel more frequent, especially right now. We have been dealing with cascading traumas over the past few years,” Dr. E. Alison Holman of UC Irvine, health psychologist and professor of nursing and psychological sciences, told Salon. “Mass casualty gun violence events are overwhelming people emotionally and making it difficult to cope,” she said.

But it’s not just the shootings that are dragging us down. It’s the particular way that they’re filtered into our consciousness through the internet and through each other that is having a profound psychological effect on all of us.

* * *

Statistically speaking, mass casualty gun tragedies are only a small percentage of gun homicides in the United States, Holman said. Combined with the pandemic; large-scale protests sparked by police shooting deaths involving African-Americans; climate change and natural disasters; overseas wars; political events like the Jan. 6 insurrection; and a variety of other factors, the past few years have translated to a high number of people feeling extreme emotional distress and discomfort. It’s natural that our anxiety and collective trauma spills over online.

“After mass violence, there are individuals and groups that want to question if these events ever happened. They frequently leave comments on news stories and blogs. They also directly contact the loved ones, the first responders and others in the community [who were there]. They will ask if the gun violence ever happened.”

And about that online world: we’ve all experienced the unpleasantness of arguing with a stubborn or hateful troll. Yet gun violence survivors and their family members have a particularly rough go of it in online spaces, Brymer says. Often, such individuals and groups related to combatting gun violence receive frequent unwanted contact via social media.

“After mass violence, there are individuals and groups that want to question if these events ever happened. They frequently leave comments on news stories and blogs. They also directly contact the loved ones, the first responders and others in the community [who were there.] They will ask if the gun violence ever happened,” she said.

Indeed, shockingly naïve and hare-brained conspiracy theories abounded after the Sandy Hook shooting, and were infamously propagated by radio personalities like Alex Jones. Jones’ associated companies were forced to file for bankruptcy for his role in spreading lies about the Sandy Hook shootings.

“You might have seen that from Sandy Hook or Parkland. We are seeing this happen in nearly all mass shooting events … family and others are being asked to show if they have proof that the mass shooting happened,” she said. “The distressing aspect is that the questioning is… taking place on social media, through private messages and public posts,” Brymer said.

Those directly involved in a gun violence event should adjust one’s social media privacy settings to avoid unwanted online contact, said Brymer. The same advice mental health experts give to children, also work for adults, including those who were not present. If you are overwhelmed with a recent gun violence incident, don’t watch and rewatch videos and graphic pictures. Don’t look at real-time videos where people’s lives are ending due to gun or other violence. If you are looking for news and specific information about the gun violence incident, consider reading the text of a news article online, but avoid reading the comments and clicking “play” on videos, experts say.

Secondhand trauma

Even those of us with no personal connection to a gun violence event may feel heartbroken after reading about school children dying, said Dr. Melissa Brymer, director of Terrorism and Disaster Programs at UCLA/Duke National Center for Child Traumatic Stress.

“As adults, we believe that we are going to die before our children. There is research that shows adults experience significant levels of profound shock, anger and sadness when children die, especially during mass casualty tragedies. And we are seeing many adults feeling this across the country,” said Bymer. “Schools are supposed to be a protective shield,” she said. As adults we are feeling more vulnerable, and asking questions like, ‘Can we protect our kids?’ “

Research shows that individuals with a history of trauma may be even more compelled by both individual and collective grief to feel sadness, frustration, and anger. Using, but not overusing, social media and technological devices may be a way to connect — for some. But know your limits.

RELATED: Uvalde shooting timeline exposes an ugly truth: The police have no legal duty to protect you

Keema Waterfield, the Montana-based author of the memoir “Inside Passage,” was harmed by a gunman in her childhood. While Waterfield’s childhood trauma did not involve a mass shooting incident or any deaths, it had long-lasting repercussions: today, as an adult and parent of two young children, when she hears about these mass tragedies, it can be hard for her to process.

“I see the headlines and throw my phone down. I have to take a couple of breaths to absorb the information. At that moment, I am very frozen by it. I feel overwhelmed,” Waterfield said after seeing the news alert about the deaths of 19 school children and 2 teachers in Uvalde, Texas.

Scientific research backs up Waterfield’s strong physical and emotional response. Past trauma, including, but not limited to gun violence, may mean that sensitive individuals could become triggered and then physically and emotionally distressed by a gun tragedy they have no personal connection to.

According to the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions, “gun violence can have lasting impacts on health and wellbeing.”

According to Dr. Sandra Graham-Bermann, director at the University of Michigan Child Resilience and Trauma Lab; and Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry, there are both short and long-term impact as the brain reacts to traumatic events. “It operates on three levels,” Graham-Bermann said. “At first, there is the fight, flight or freeze response. The body goes on high alert, blood pressure rises, heart rate increases, in preparation for reacting to the threat.”

She continued: “The second level of functioning is the limbic system — here the chemicals in the brain moderate the emotional reactions. The fear center in the brain is the amygdala. It becomes activated in threatening situations. The third, and highest level, is the neocortex. Here, thinking comes into play so we can evaluate the threat and we make reasoned decisions about the extent of threat, the best course of action, etc.”

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

According to Graham-Bermann, the levels of the brain are correlated with the immediate response to stress, and take about 2-3 seconds. Then, the intermediate response to stress typically lasts 20-30 seconds. The prolonged effects of stress could extend for hours, days and weeks after the trauma, she said.

Some individuals get stuck in a loop and that translates to pent up anger and frustration. Once again, some may feel they need to express anger and frustration online, getting stuck.

Reactions differ across different demographics

Nationally, Black and Hispanic/Latinx Americans report being exposed to violence at rates twice that of White Americans, many of whom have personally witnessed gun violence. According to the The Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence , a 2018 nationally representative poll of American adults found that 27% of Black Americans had witnessed a shooting, while 23% reported that someone they care for has been killed by a gun. Among Hispanic/Latino Americans, 22% reported that someone they cared for has been killed by a gun.

While we may have some familiarity with the in-person risks of gun violence exposure, going online and seeing upsetting images or watching and rewatching camera footage or other recordings of people’s death by gun violence can also do more harm than good, especially for those with past trauma.

“It helps to talk with and communicate with other people about how you are feeling so that you are not alone in suffering. It also helps to track down factual information rather than relying on sensational coverage or extreme and harmful information.”

“For the general public, one of the important ways we can protect ourselves in the aftermath of such gun violence is to reduce exposure to the horrific images and stories about the violence,” said Graham-Bermann.

“We have to take into account the context of the trauma too. If the trauma is racially motivated, like with the upstate New York murders, then the traumatic stress burden is greater,” said Graham-Bermann.

Naturally, being part of a particular ethnic, cultural or racial group, religious group may mean some people may spend more time than usual looking at news stories, pictures, videos and social media as a way to honor the individuals whose lives were lost.

“It helps to talk with and communicate with other people about how you are feeling so that you are not alone in suffering. It also helps to track down factual information rather than relying on sensational coverage or extreme and harmful information,” Graham-Bermann said. She noted that survivors of trauma, including those of color, also turn to spirituality, group organizations, and religious organizations for support.

According to UC Irvine’s Dr. Holman, if an individual finds they continue to feel extreme rage following a gun violence incident and/or are spending excessive time posting angry online rants or debating gun violence with strangers online, it’s possible to find a way out of the social media/online rabbit hole.

Holman, who teaches classes on compassion, said “One of the most important things is to reach out and connect with somebody, showing compassion for others,” she said.

This extends to connecting online and on social media, she said, but could include the offline world — meaning finding individuals and organizations, online and offline, that align with your beliefs and values.

Not only does research show the real benefits of compassion for those who have undergone a gun violence event, but also to those who are showing compassion.

“There are benefits for the community…Compassion helps provide people with a sense of purpose, of meaning, it brings people together,” Holman said. Thus, the way out of the social media rabbit hole, Holman says, is positive connection — face to face or online.

Read more on gun violence and mass shootings in America: