When Roy Choi talks about kitchens, he doesn’t start with knives or flames or even food. He starts with time. Or more precisely, the way you lose it. “It’s like a casino,” he says. “No clocks, no windows.” One minute you’re dicing daikon, the next you look up and it’s midnight. The world outside vanishes. In its place, a new reality forms — one built on precision, compulsion and a kind of underground devotion that most people never see.

This is the world Choi came up in. And it’s the world he’s been gently, fiercely reimagining ever since.

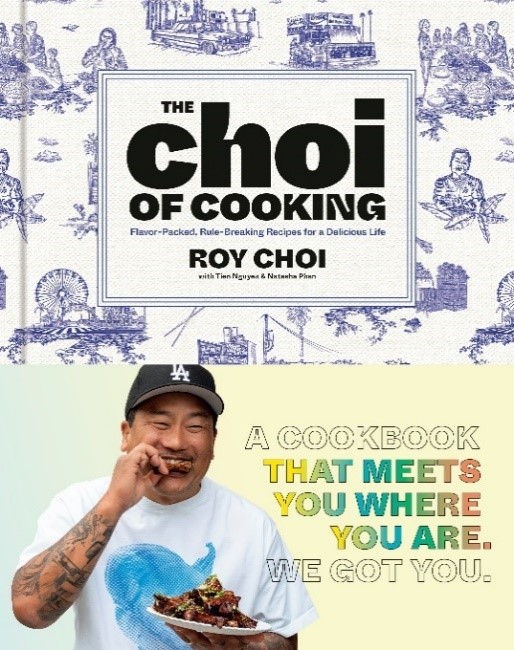

In his new book, “The Choi of Cooking,” co-written with Tien Nguyen and Natasha Phan, he writes with the same raw honesty he brings to his food. He talks about doomscrolling with snacks, about Red Vines and Spaghettios, about masculinity and shame and what it means to feed yourself like you matter. He makes the case for vegetables that “move in silence like a G,” and he builds bridges — for skaters, for kids, for anyone who’s never seen themselves reflected in the wellness aisle.

This isn’t your typical healthy cookbook.

It’s a magnum opus from the culinary icon behind Kogi, “L.A. Son,” and “The Chef Show” — a book built on balance and compassion. There are 100 flavor-packed recipes here, but also something deeper: a realistic, affirming way to approach eating well without going to extremes.

Yes, there’s a Kimchi Philly Cheesesteak. Yes, there’s Cold Bibim Noodle “Salad.” But there are also vegetable-forward hits like Calabrian Chile Broccoli Rabe and comfort bowls like Veggie on the Lo Mein Spaghetti. And when you’re ready, Choi offers “Power Up” tweaks to make even the crispy mashed potatoes a little more nourishing.

“The Choi of Cooking” is about steps, not leaps. It’s about reaching for health without ditching joy. It’s about building a life that feeds you — body, heart, and soul.

I spoke to Choi about losing time, finding balance, disrespecting your vegetables and what it means to write a new menu for your younger self.

This conversation has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

One thing that really stuck with me in your intro essay was how you describe working in a professional kitchen as kind of like being in a casino. It’s one of those places where you just lose time. I was hoping you could explain that a little more for folks who haven’t worked in kitchens — and maybe also talk about how that experience affects your physical and mental health?

Roy Choi: Yeah, I think it’s like any craft or hobby that fully absorbs you. Practicing in a band, working in a woodshop — there’s a similar feeling. The casino comparison comes in with the way time kind of disappears. No clocks, no windows. You’re almost subterranean, but not in a bad way. You choose to be there. That’s part of it —you’re voluntarily entering this underground vault where your entire focus is on the task in front of you.

When I talk about losing time, I mean that sense of being cut off from the world above ground. You get so immersed in what you're doing that it takes up all your senses, all your attention. You forget what time it is. You lose your thread to reality because, in a way, you’re building a new one. You start to live by different rules — new ethics, a new mandate — and that shift starts to feel normal.

It’s a little like gambling. In a casino, you start seeing patterns, telling yourself, If I just do this, then that’ll happen. You begin to set up this whole logic, even though it’s kind of a house of cards. It’s the same in the kitchen, except it’s not necessarily an addiction — it’s a compulsion driven by care and pride. You tell yourself, If I stay one more hour, I can finish this prep. I can’t leave this task undone. And suddenly, it’s been 12 hours, you haven’t seen daylight, and you’ve convinced yourself you’re the only one who can do it.

That’s where it can start to get a little destructive. You get into a mindset where you don’t trust anyone else to take over. You don’t delegate. You shoulder everything yourself. And that whirlpool — getting lost in your own head about being the only one who can pull it off — that’s where the danger lies. That’s when it starts to eat at your health, mentally and physically.

We need your help to stay independent

Also in that essay, you write really candidly about your relationship with food. From the Red Vines and Spaghettios days to the angry chef era, working through it in the kitchen. And I say this as someone who’s worked in food and struggled with food: I was curious, from your point of view, how you learned to differentiate between what your body was asking for and what, for lack of a better word, your demons were craving. Does that make sense?

Yeah. And I think that’s true for a lot of cooks — or anyone burning the candle at both ends. Not just chefs, but also doctors, journalists, creatives . . . people who don’t live on a 9-to-5 clock. Sometimes it’s not even a 12-hour clock — it just keeps going.

For me, that pace became unsustainable. I was holding it together with Scotch tape and paper clips. On the outside, I was a chef. During the day, I was prepping and tasting healthy stuff — green beans, spinach, buchu, daikon, snow peas, garlic, galangal. Constantly putting good food in my body, even if it was just a bite at a time. But the minute I punched out? Everything flipped. Red Vines. Frozen lasagna. Spaghettios. Taco Bell. I called it doomscrolling, but with food — eating my way down a dark hole.

I kept that up for years. This fragile balance. Eventually, my body broke down. And I started seeing the same thing in people around me — especially folks from my generation. We grew up on fast food, and now so many legends are dying at 50, 55.

Back then, we didn’t have the language, or the courage, to talk about it. No one wanted to hear it. It felt like telling a joke that didn’t land or lecturing people who didn’t want to be lectured. But now? We’re ready. Our communities are feeling it. And especially as a man, it was hard to confront. Because eating like crap was tied to masculinity. Pizza, beer, double bacon burgers. If you said, Hey, I don’t want that tonight, people looked at you sideways. But those chains are breaking. The food world’s more diverse. There’s more information, more tools. And we’ve got each other.

"Wellness can feel shame-y. Like if you’re not in yoga pants on day one, you’ve already failed. But that’s not real. What’s real is starting small. Baby steps. Building bridges — ways to start without giving up everything you love. "

I was living that unsustainable life, but I was able to confront it. And I know a lot of people still can’t. That’s part of why I made this book. It’s not just for folks already deep in wellness. It’s for people who haven’t even taken the first step.

Because wellness can feel shame-y. Like if you’re not in yoga pants on day one, you’ve already failed. But that’s not real. What’s real is starting small. Baby steps. Building bridges — ways to start without giving up everything you love. That’s what I needed. A bridge. A way to say: OK, I can still have a burger, pizza, a pint of ice cream. But little by little, I’ll move the line.

First it’s 70/30. Then 60/40. Maybe one day it’s 50/50. But the real goal? Just take the first step.

It's interesting that you talk about how you grew up. There was this line that really stood out to me: “I would have made these dishes if I was the one in charge of writing the food in my childhood script.” So I was curious, if you were cooking for a kid — or time-traveling and handing your younger self a recipe — what do you think you would have wanted to receive, and why?

Well, I see it firsthand now, because we don’t have kids’ menus at my restaurant and I cook the food that line is talking about. I cook food that’s full of flavor bombs but also packed with nutrients. I’m not a nutritionist or anything — I’m not looking at calories — but I am trying to walk a line that’s at least better than chicken tenders and French fries, you know what I mean? If something’s even a little bit better, then it’s better. We just have to shift our thinking around how we measure that.

So I cook with full heart, full flavor — lots of aromatics, herbs, chilies, hot sauces — all these flavor bombs. But when you eat it, it feels like comfort food. There’s no lecture, no nutritional breakdown. It’s all hidden between the lines. In a way, it’s like a reverse-Trojan horse.

The outside is this big, drippy, cheesy, craveable thing — but inside, it’s got all these good ingredients. Like the Cheesy Wheezy — that’s the perfect example. You look at it and think, this is wild. It eats like a pepperoni pizza, right? But if you break it down, it’s made with great sourdough, high-quality cheese and a sauce that’s got maybe 14 different fruits and vegetables in it. There’s banana in there! Good butter. Good everything.

So it hits like greasy, cheesy, crunchy fast food, but underneath, it’s all made with care. That’s the matrix, the math behind the joy of cooking, you know?

"The Choi of Cooking" (Clarkson Potter)I think it might’ve been the first “step-by-step essay” in the book, the one where you’re talking about cooking for some of the skaters you knew and how they kind of moved from “from vapes and Molly to grapes and cauli.” I think it says something really beautiful about how the food we make for ourselves — or even just what we put into our bodies — can actually change how we feel about ourselves. Is that something you’ve experienced?

"The Choi of Cooking" (Clarkson Potter)I think it might’ve been the first “step-by-step essay” in the book, the one where you’re talking about cooking for some of the skaters you knew and how they kind of moved from “from vapes and Molly to grapes and cauli.” I think it says something really beautiful about how the food we make for ourselves — or even just what we put into our bodies — can actually change how we feel about ourselves. Is that something you’ve experienced?

Again, this is something I’ve seen firsthand. Not only did I live it, but I experienced it all over again when I opened Kogi.

Kogi was so democratic in how it served food. We embedded ourselves in neighborhoods, and it wasn’t just a privileged few who came to eat with us. We were like fireworks on the Fourth of July at a block party. Everyone was invited. Everyone participated. What I saw — especially in that teenage age range, like 14 to 19 — is that, when you’re growing up, especially going through puberty and navigating all these social obstacle courses, you put on a tough exterior. You can be standoffish. Sometimes you’re even ashamed of liking things that feel soft or good.

You know, it’s like that old stereotype of hiding your books under your pillow because you don’t want people to know you’re a reader? You’re reading under a blanket with a flashlight. And it’s like that with food too.

It’s not always “cool” to eat a bag of carrots. You’re supposed to eat the Crunchwrap, right? And adults assume that’s what kids want, so we lean into the lowest common denominator — which actually harms them, because those are the most important years for development.

That’s what that essay is really about. I was still really connected to that younger part of myself, and to actual young people. And I wasn’t afraid to say to them, Yo, you should try this. Because I knew that once they did, their world would open up. And the flavor, the experience — it would give them the confidence to step into that new space.

"You know, it’s like that old stereotype of hiding your books under your pillow because you don’t want people to know you’re a reader? You’re reading under a blanket with a flashlight. And it’s like that with food too."

A lot of times that confidence is missing not because someone is stubborn, but because they’ve never had the chance to experience something different.

I had that moment myself the first time I tasted real Parmesan cheese. Before that, I only knew the Kraft shaker bottle. And then I tasted real Parmigiano-Reggiano, and it blew my mind. It opened my world. I saw Italy differently. I understood cheese differently. I got aging, microbiology — the whole thing.

So now that I can share that with others, I do.

At the Kogi truck, I’d be introducing asparagus to a bunch of kids — skaters eating five-year aged cheddar. It opens their minds. And I know, as a chef, that once you taste that, you can’t go back. What would happen is, the first week, they’re standing across the parking lot, spitting loogies and saying, “I ain’t gonna try that. That’s for wussies.” But they try it. And the next week, they come back like, “Yo, you got any more of that asparagus?” And it’s like — it’s like a drug, in the best way.

That ties into another great line from the book, where you talk about vegetables that, quote, “move in silence like a G.” I was hoping you could talk more about your approach to working vegetables into your food in a way that doesn’t feel like a chore. Because honestly, the vegetable section in this book could get anyone excited to eat vegetables — even people who never thought they were “veggie people.”

First answer: get a blender. That’s step one. Blend everything — make it a sauce, a vinaigrette, a green juice, a soup, whatever. The second it’s blended, you stop seeing it as “cauliflower” or “that weird-ass leek you don’t know what to do with.” Once it’s in that form, you can steer it in any direction.

But here’s the deeper thing. I think, in a weird way, we’ve all been taught we have to respect vegetables. Like, it’s encoded in us.They're “healthy.” You “have to” eat your vegetables. They’ve got this angelic glow, right? They’re pristine. There’s this whole vibe of, “Let the vegetable shine.” You hear chefs say that all the time: “I’m a great chef because I don’t mess with the ingredients.” Like, f**k that, man. Go the opposite direction.

Disrespect the s**t out of vegetables. Beat them up. Blister them. Puree them. Add tons of chili, vinegars, sweet stuff. Throw in something ridiculous you love. You like pepperoni pizza? Cool, puree pepperoni with vegetables.

Totally cross the line.That’s what I mean when I say they move in silence like a G. Because right now, not enough people are eating vegetables and what do we do? We keep making them more precious. More protected. More . . . pompous. How are we ever gonna get people excited about vegetables if we keep treating them like some museum exhibit?

No, we need to move the line in the other direction. Make them taste like junk food. Make them craveable. Make them fun. And then maybe people will actually eat more of them.

“Disrespect your vegetables”— I like it. What I really appreciate about this book is that it’s not a detox book. It’s not a “clean eating” book in that weird, rigid way. It feels way more real. And honestly, way more lasting, especially for people who are new to this. So I’m wondering: big picture, what do you hope people take away from the book? Like, if there’s one message, what would it be?

That it’s a start. That’s all. If you’re looking for a start, this book is it. I want to be that friend with his hand out, saying: You can hold on to it. Like the first time you try to ride a skateboard, and you’re scared — but someone holds your hand and helps you get going. That’s what I hope this book can be. A hand to hold when you’re trying something that feels intimidating or brand-new.

That’s really the heart of it: just to start.

I think of the book as the beginning of a three-part series—even if I never write Part Two or Part Three. This one is Step One. Yeah, there are recipes in here that a health expert might look at and say, That’s not healthy. But you have to see the whole book as a composition. And taken as a whole, I think it is healthy.

That’s how I designed it — something you can use as a first step. And then, if there was a second volume, it would take it further. By the third volume? It’d probably be full-on salt-free spa cooking, but still done in a new, flavor-forward way.

"Disrespect the s**t out of vegetables. Beat them up. Blister them. Puree them. Add tons of chili, vinegars, sweet stuff. Throw in something ridiculous you love. You like pepperoni pizza? Cool, puree pepperoni with vegetables."

So that’s the trajectory. And this book — this one right here —is the start of that arc. And I’ll be real with you, this is personal. My best friend died from a combination of obesity, malnutrition, heart failure. I’ve had other friends go through it, too. People who lost limbs, who lost their lives, because of diabetes or other complications tied to food.

And at the time, I wasn’t ready. I couldn’t help them, even though, in their own way, I think they were asking me to.I wasn’t the person I needed to be back then. But this book . . . this is my way of honoring them. I can’t go back in time and change what happened. But I can make something now — something that might help someone else.

That’s what this book is about.

That really comes through in the tone of the book. It’s not just a guide to flavor. It’s a . . . OK, this is gonna sound absolutely cheesy and I’m sorry — but to me, it feels like a book about being kind to yourself.

No, that’s exactly it. Sorry to jump in — but that’s the core message. To have the courage to be kind to yourself.

What does that look like for you these days? Being kind to yourself — in the kitchen and outside of it, if you're open to sharing.

Yeah, I’m down to talk about that. A lot of it comes down to my eating habits, honestly. It’s like going to the gym, right? You’ve got to work new muscles. For me, it’s about training those muscles around habits and cravings. Because it does take work. And being kind to yourself means doing that work. When you’re not being kind to yourself, it often shows up as not investing in yourself — physically, mentally, emotionally. For me, one of the easiest places that shows up is in snacking. Snacking is one of the fastest ways to be unkind to yourself —especially if you're just reaching for whatever.

So lately I’ve been shifting those habits. From chips to nuts. From candy to fruit. From soda to juice. From juice to green juice. Those little moves — that’s been a big part of my self-kindness.

And then outside the kitchen? It’s also about being OK with not being exactly where you want to be. That’s hard for me. I’m someone who wants to get everything done — and sometimes that gets in the way of really listening. To people. To the moment. To the universe, honestly.

When we’re unkind — to ourselves or others — it often starts with not listening. So I’m trying to give myself more space and time to absorb things. To take them in before reacting.

"The Choi of Cooking" is now available for purchase.

Read more

about this topic