On the night before Thanksgiving, Rahmanullah Lakanwal, an Afghan immigrant who had served with the CIA in the war against the Taliban regime, shot two members of the West Virginia National Guard in Washington, D.C. (One of them, Spc. Sarah Beckstrom, later died of her injuries; the other, Staff Sgt. Andrew Wolfe, was critically injured but is likely to recover.)

In his comments on the tragedy, Donald Trump called Afghanistan a “hellhole on earth” and announced a halt to all Afghan immigration, along with renewed vetting of all Afghans admitted during Joe Biden’s term in office. White House deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller later posted that immigration does “not just [import] individuals. You are importing societies… migrants and their descendants recreate the conditions, and terrors, of their broken homelands.”

Here’s what the U.S. government will never tell you: If Afghans are trying to leave their homeland, that’s because U.S. policy has made Afghanistan unlivable for so many. And if Lakanwal committed an act of domestic terrorism, that happened because the CIA trained him for a life of violence. These tragedies did not come out of nowhere. Their roots go back decades. Yet every new presidential administration feeds Americans a new story about Afghans and Afghanistan, and each story is deployed to rewrite history and distract Americans from understanding their nation’s past.

I know this because I myself am a “descendant” of an Afghan immigrant from a “broken homeland,” and I grew up immersed in these narratives. I remember watching Dan Rather on the CBS Evening News with my Afghan father as a young girl in the 1980s. Every few days, Ronald Reagan would appear on screen at a podium, declaring how much he admired Afghanistan, and my father would frantically press “RECORD” on the remote to capture Rather’s latest report on VHS tape. To hear it from Reagan, Afghanistan was one of the most beautiful, freedom-loving and God-fearing places in the world.

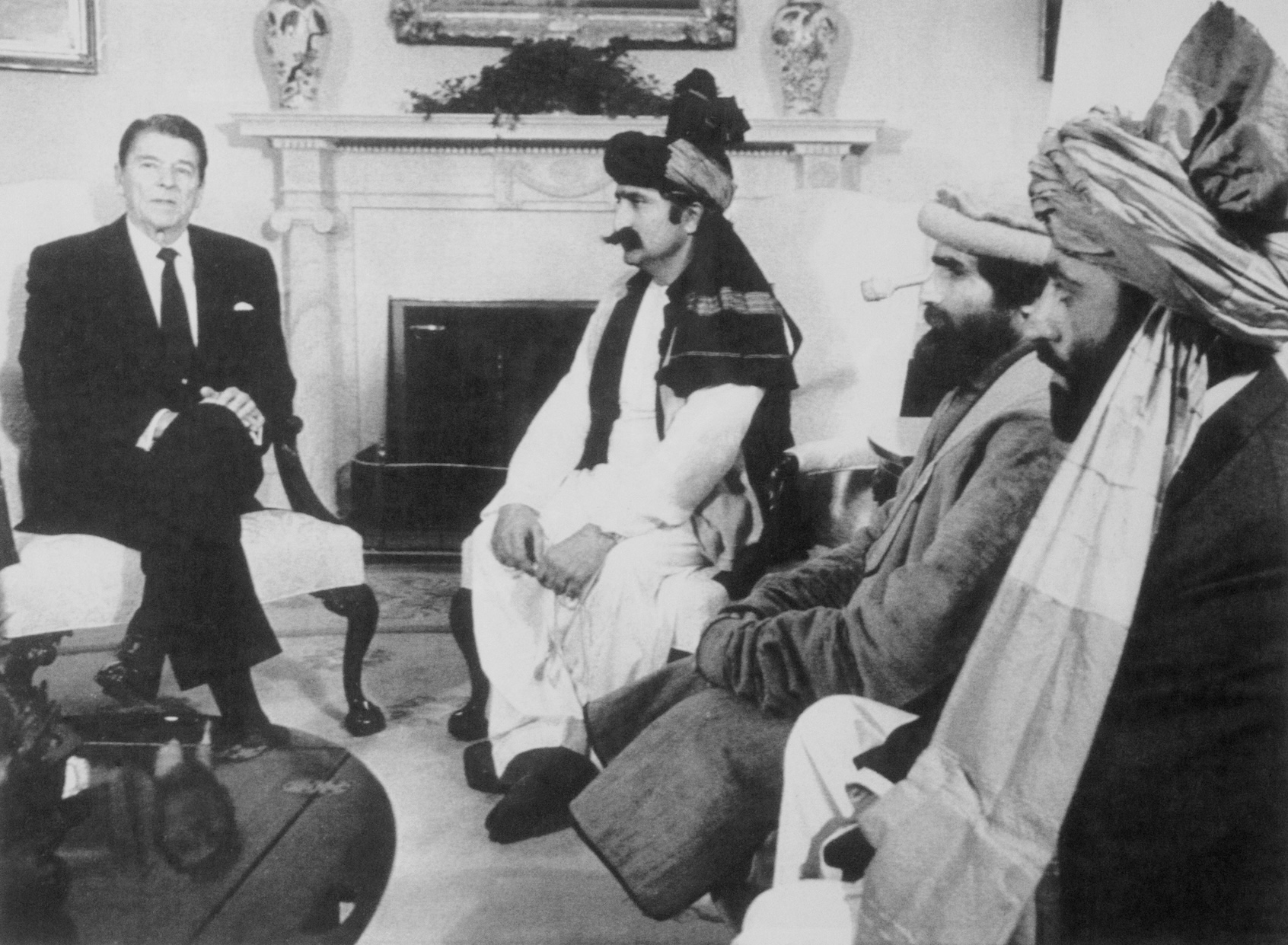

In 1982, Reagan issued Proclamation 4908 to declare March 21 Afghanistan Day. In his speech he dedicated the launch of the space shuttle Columbia to the Afghan people: “Just as the Columbia represents man’s finest aspirations in the field of science and technology, so too does the struggle of the Afghan people represent man’s highest aspirations for freedom.” The following year, he invited Afghan mujahideen — or as he called them, “Freedom Fighters” — to the White House to discuss their resistance to the Soviet occupation that began in 1979. Amid a cluster of media in the Oval Office, Reagan lavished his visitors with praise. Afghanistan, he said, was “a nation of heroes.” In 1985, in another White House meetup, Reagan called the mujahideen “the moral equivalents of America’s founding fathers.”

So what happened between then and now? How did Afghanistan go from being Ronald Reagan’s “Nation of Heroes” to Donald Trump’s “Hellhole on Earth”? How did Afghans go from honored White House guests to immigrants blamed wholesale for the actions of one disturbed individual?

* * *

What both Reagan and Trump’s stories have in common is the attempt to redefine Afghans and reduce them to caricatures. In these narratives, Afghans are either all good or all bad, pure heroes or absolute terrorists. And as wildly divergent as these claims seem, they share a single goal: They are designed to distract Americans from the reality of U.S. policies that have destabilized Afghanistan, exploited, displaced and killed Afghan people, and weaponized Islam.

Amid a cluster of media in the Oval Office, Ronald Reagan lavished his visitors with praise. Afghanistan, he said, was “a nation of heroes.” Later, he called the mujahideen “the moral equivalents of America’s founding fathers.”

U.S. involvement in Afghanistan did not begin after 9/11, as many Americans may assume. Let’s rewind to 1978, the year Afghanistan underwent a communist revolution. For more than 30 years before that, effectively since World War II, Afghanistan had served as a buffer state between the American and the Soviet empires. Located on the southern frontier of the USSR, my father’s homeland was supposed to be, from the U.S. perspective, a containment zone against further communist expansion.

U.S. policymakers sought to out-compete the Soviet Union and to win Afghans’ hearts and minds with all kinds of infrastructure and investment: universities, hospitals, highways, hydroelectric dams, irrigation projects and more. That was why my father was educated by American teachers, both at the Afghan Institute of Technology and at Kabul University, after which, in the early ‘70s, he was granted U.S. funds to attend grad school in New York state, where he met and married my American mother.

But when a pro-Soviet regime came to power in Afghanistan, the U.S. saw that as a critical strategic defeat. Jimmy Carter and his national security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, however, saw a way to fight back. The Afghan communist government’s social and economic reforms were proving unpopular, and Islamic resistance was brewing. Perhaps Islam could be used as a weapon against communism? By strengthening religious insurgents, the U.S. hoped to bait the Soviet Union into invading its southern neighbor to save the imperiled communist regime.

Brzezinski would later reveal that Carter approved CIA support for the Afghan mujahideen resistance even before the Soviet invasion. The U.S. wanted to turn Afghanistan into a battlefield, Brzezinski explained: “The day the Soviets officially crossed the border, I wrote to President Carter, in essence: ‘We now have the opportunity to give the USSR its Vietnam War.’” More than a million Afghan civilians would die in that conflict, and more than six million would become refugees.

* * *

When I was growing up in upstate New York in the ‘80s, my family didn’t know any of this. We believed Reagan was a great American leader, sticking up for the underdog against the evil Soviet empire. Why wouldn’t the U.S. support Afghanistan, after all? Afghans were cool! Even Rambo liked us! (Check out the plot of “Rambo III” from 1998.) We had no idea that the U.S. wanted the Soviets to invade Afghanistan, or that American officials hoped Afghanistan would become a “Vietnamese quagmire” for the Russians. We also didn’t know the U.S. was weaponizing our religion.

Operation Cyclone, which began under Carter’s watch with the help of Brzezinski and extended through Reagan’s two terms, remains, to this day, the largest covert CIA operation in American history. And it didn’t arm only Afghan mujahideen. It was a campaign to gather thousands of religious militants from across Southwest Asia and North Africa into Afghanistan to take down the Soviet Union. It was quite literally global jihad, as a Cold War gambit sponsored and funded by the U.S.

Operation Cyclone, which began under Jimmy Carter’s watch and extended through Reagan’s two terms, remains, to this day, the largest covert CIA operation in American history. It was global jihad, as a Cold War gambit.

For me, the weaponization of Islam is best symbolized by the educational textbooks deployed by the U.S. government, which taught Afghan boys, in the guise of school lessons, that jihad was their duty as Muslims. I often think back to my days in elementary school, learning my ABCs and how to count with images of Apples, Balls and Cats, while Afghan boys learned their lessons with grenades, switchblades, bullets and rifles. Here is a page from a U.S.-funded first-grade Pashto and math booklet created by University of Nebraska for kids in Afghanistan and Afghan refugee camps in Pakistan:

(University of Nebraska at Omaha/Public domain)

(University of Nebraska at Omaha/Public domain)

When Soviet forces withdrew from Afghanistan in 1989, followed by the collapse of the entire Soviet empire two years later, Operation Cyclone wound down. Mission Accomplished, so to speak. When Bill Clinton campaigned for the presidency in 1992, he didn’t mention Afghanistan even once. After his election, he ignored State Department warnings that, after all the CIA funding of religious extremism and all the weapons and militants collected within Afghan borders, a new Afghanistan was emerging.

The nation was embroiled in civil war and becoming a haven for stateless soldiers, for jihadist training camps, for violent insurgents exiled from their own homelands, for veterans of the anti-Soviet war looking for their next battle. Clinton didn’t listen when he was informed that a Saudi veteran of the Afghan-Soviet war named Osama bin Laden was building a paramilitary base in Afghanistan’s mountains to train soldiers for a holy war against the U.S. Within two years of taking office, Clinton canceled all humanitarian and developmental aid to Afghanistan.

We need your help to stay independent

The narrative machine stopped. There was nothing Clinton wanted from Afghanistan. I left home for college during his first term, just as the reverberations of Operation Cyclone began to blow back on the U.S. In 1993, a truck bomb blew up in the parking garage under one of the World Trade Center towers. The leader of that plot trained with al-Qaida in Afghanistan. (He had hoped to make one tower hit the other like a domino, so they’d both go down at once.) In 1996, a truck bomb at Khobar Towers in Saudi Arabia killed 19 U.S. airmen and injured hundreds more. That attack was carried out by Saudi veterans of the Afghan war. In 1998, two U.S. embassies — one in Kenya, one in Tanzania — were attacked with truck bombs that exploded minutes apart, killing more than 220 people. Synchronized explosions — that was the bin Laden signature. Afghanistan’s new mujahideen leaders, the Taliban, refused U.S. demands to give him up.

Earlier in 1998, Brzezinski had dismissed concerns about the consequences of Operation Cyclone: “What was more important in the view of world history? The Taliban or the fall of the Soviet empire? A few stirred-up Muslims or the liberation of Central Europe and the end of the Cold War?”

* * *

After Sept. 11, 2001, the narrative machine turned back on. A month after the World Trade Center attacks, the U.S. invaded Afghanistan — for real this time, not through proxies — in an effort to annihilate the perpetrators, who came out of the same mujahideen culture and radical faith systems that the U.S. government had funded and supported for years. For this new “Global War on Terror” against al-Qaida, a new vocabulary and a new story were in order. Mujahideen would no longer be translated as “freedom fighters.” Mujahideen were now terrorists.

Start your day with essential news from Salon.

Sign up for our free morning newsletter, Crash Course.

George W. Bush reduced decades of Cold War geopolitics and bloody gamesmanship to a simplistic formula: “We love freedom, they hate freedom.” First lady Laura Bush added a fresh twist, throwing some feminism into her historic national radio address. This war, she explained, would have the added perk of saving Afghan women: “The brutal oppression of women is a central goal of the terrorists… the Taliban and its terrorist allies were making the lives of children and women in Afghanistan miserable…” Images of Afghan women in blue burqas began circulating in the media. Suddenly, the U.S. cared about Afghans again.

During the 20 years of war that followed, half a million more Afghan civilians died and at least another six million were displaced. After the U.S. withdrawal in 2021, the Taliban returned to power within weeks. Joe Biden blamed this humiliating and expensive failure on Afghans. In a complete reversal from Reagan’s veneration of Afghan heroes, Biden claimed Afghans were cowards: “Afghan forces,” he said, “are not willing to fight for themselves.” And here we are now, at Trump’s overtly racist claim that Afghanistan is a “hellhole on earth.”

After the U.S. withdrawal in 2021, the Taliban returned to power within weeks. Joe Biden blamed this humiliating and expensive failure on Afghans.

From Reagan to Trump, the stories Americans are served about Afghanistan have been designed to erase geopolitical and colonial histories and reduce our people to stereotypes or cartoon fantasies of “heroes” or “terrorists.” Ordinary Afghans are the people who have suffered worst from America’s manufacture of terrorism. To be Afghan is to try to hold your families and communities together while a succession of narratives are remixed, unmixed, overturned, reformed, forgotten and reinvented — and deployed as weapons against your people. To be Muslim is to have your people selectively admired and supported, bombed and abandoned, or detained and deported, depending on the latest U.S. foreign policy or a president’s desire to distract media attention from personal scandals. Afghans and Muslims remain the same human beings throughout this process, but the U.S. gets to decide what kind of humans we are, and when we are to be loved or hated.

I don’t know anything about Rahmanullah Lakanwal besides what I’ve read in the news. Reportedly, he was recruited by the CIA as a teenager and was part of the Zero Unit, which has been accused of war crimes against Afghan civilians. He was used as a tool in the “War on Terror” and, since coming to the U.S. in 2021, had been working as an Amazon delivery driver. For me, these bits and pieces of one man’s story connect to the longer and more tragic tale of the American-Afghan century, now erased in near-total amnesia.

When I think about Trump’s new policies, freezing all immigration and visa processing for Afghan nationals, I think about the Afghans who simply want to live, who want to build futures for themselves and their families. I think of the artist I helped get out in 2021, who made sculptures about the Taliban’s ethnic cleansing of his people. I remember the women’s rights activist who had to escape when the Taliban returned to power. I think of the professor who taught queer theory at Kabul University who hid in Islamabad with his wife and daughter while they waited for visas. I worry for my friend who fled the Taliban because his calls for human rights made him an immediate target. His green card, and those of his wife and three kids, are now in question.

American people need to listen to Afghans rather than to the opportunistic, flip-flopping, world-destroying narratives of U.S. leaders. Let Afghans tell you their stories about how they’ve built and rebuilt their lives. Let us tell you about the good people who have disappeared, the girls fighting to read, the boys caught in armed conflicts, the men and women holding their families and communities together despite everything. Let us tell you how diverse and beautiful we are, no matter what any president says about us and how much we’ve lost. Afghanistan has been central to American history for almost a century. If our homeland is “broken,” that happened because this country is broken too.

Read more

on the Afghan war and its aftermath