In the state of abject gloom and pitiable terror in which, having turned the last page of Jan Bondeson's harrowing treatise "Buried Alive: The Terrifying History of Our Most Primal Fear," I now find myself -- but I am merely very nervous, nothing more; why will you say that I am mad? -- the precise circumstances surrounding the fatal assignment to review it are, I confess, as evanescent as the phantasms that flit through the mind of the groaning heretic as he rides in a cart through chanting streets toward the unknown horrors of the auto-da-fé. Yet perhaps it is even now possible to summon up the fatal scene. I vaguely recall sitting in an inn of oddly Bavarian appearance, surrounded by what appeared to be stein-wielding burghers in lederhosen and pig-tailed blond waitresses in ... -- what was it? a thousand indistinct images whirl unbidden through my teeming brain ... -- extreme décolleté. In the midst of this feverish gaiety, it seemed to me that one of my colleagues suddenly stood up, brandished J. Bondeson's tome above his head and, with a youthful rashness recalling Jonathan Harker in his Transylvania-real-estate-promoting phase, demanded that we review it.

Madness! Horror! The unbroken Reign of Chaos and Old Night! There are no words for the scene that followed, save perhaps those incoherent ejaculations that burst from the lips of The Dead upon whom the Last Judgment has been passed after the sounding of the brazen trumpet. Dimly I recall a room convulsed; -- I seemed to see pig-faced editors hurling themselves in terror toward the door; -- I observed a death-sliver moon racing through blasted clouds; -- I heard inhuman screams mingling with the wild neighing of horses, the breaking of beer steins and the squealing of the aforementioned pulchritudinous waitresses (although it is possible that these sounds were in fact only a song downloaded from Napster being played in the next cubicle).

When at length some semblance of sensibility had returned to my corporeal frame, I found myself lying alone under the table, a copy of "Buried Alive" thrust into my nerveless hand. Save for the deadly drip-drip-drip of a spilled quart of Meisterbrau, all was silence and dread.

And these horrors were but as a simulacrum, a faint imagining, of the more refined terrors that awaited me when, impelled by I know not what malignant force, I opened the airless and decaying pages of Monsignor Bondeson's putrescent treatise (Norton, $24.95 at a fine bookstore near you). Long and deeply have I read in the damned books of many ages -- the Comte de Thierrot's disquieting meditation "Couleurs et Spectaculaires de la Cité Mort"; Avezedos' hideous prolegomena "De Reribum Horribilis Monstrum"; George W. Bush's unspeakable "A Charge to Keep" -- but in none of these corrupt and eldritch tomes are such nightmares to be found. As I plunged deeper into its malignant pages I seemed to see a leering face, pushing up from the depths of Earth, growing ever nearer; -- to feel clammy hands, covered and clotted with gore, grasping me about my nether torso with an inhuman strength; -- to hear a creeping voice, croaking hollowly, whispering forever in my most secret ear "They have walled me up alive within the tomb!" When I had finished, I thrust the volume from me with a shudder; -- but 'twas too late. The grinning daemon of Terror held dominion over my soul. And there his dark Sovereignty shall hold sway -- Forevermore!

A good book reviewer should be prepared, and I took the liberty of writing the above passage before reading "Buried Alive." At the time, it seemed a pretty safe bet that Jan Bondeson's opus would drive me, if not to a laudanum- and gin-drenched stupor in the Baltimore demimonde, at least to teeth-chattering depths of terror. Certainly, the reaction of my esteemed colleague Laura Miller seemed to vouch for the hair-raising properties of Bondeson's subject. Normally Ms. Miller is the stoutest-hearted of editors (witness her obsessive, Ahab-like pursuit of the dread giant squid), but when informed that I was going to review "Buried Alive," she screamed "I won't edit that!" over the speaker phone -- upon which the line went ominously dead. To judge by the book's lurid and not altogether accurate subtitle, the publishers of "Buried Alive" believe that many people through the ages have shared -- and still share -- Ms. Miller's strong feelings. And why not? It's hard to deny that finding oneself in an airless wooden box six feet underground, listening to the wriggling approach of what Poe called "Conqueror Worm," would be one of the worst possible ways to end one's existence in this sublunary sphere.

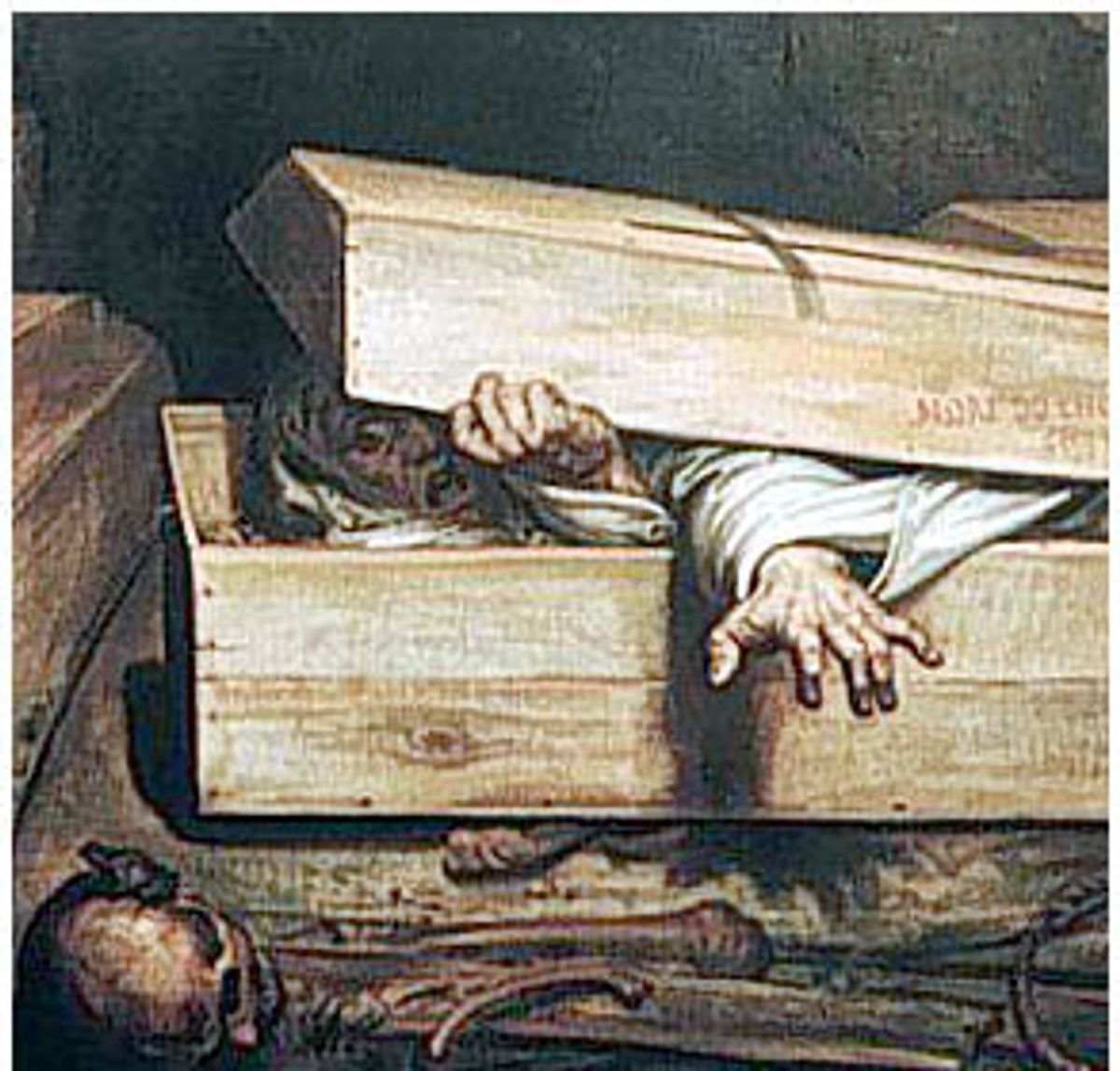

Imagine my surprise, therefore, when I discovered that "Buried Alive," far from being terrifying or even particularly creepy, was a hoot -- a cacklefest rising, at times, to a full-blown thigh-slapping laff riot. As I read I repeatedly found myself bursting out into loud, vulgar guffaws or suppressed, side-jiggling snorts -- public outbursts that were more than a little embarrassing, given the book's grim title and its cover art, a famous 19th century painting of a gaunt wretch, his eyes wide with terror, lifting the lid of a coffin upon which are stamped the words "Mort du cholera." One old lady sitting next to me on the bus, observing me chortling uncontrollably over a particularly juicy passage, moved hastily away, giving me a look that made it clear she regarded me as little more than a well-dressed Jeffrey Dahmer.

"Buried Alive" sheds light on one of those completely ridiculous yet deadly serious manias that pop up in human history now and then, like comic relief from the usual wars, famines and reality-based TV shows. In this case, that mania was an extravagant fear of being buried alive -- a fear that gripped the two most civilized nations in Europe and that lasted on and off for close to 150 years. Germany takes the top prize for this craze, with France coming in a close second, but both America and Britain had their moments as well. Bondeson's achievement here is to have unearthed a bizarre chapter of social history that, as far as I know, is almost completely unknown outside of those ghoulish circles frequented by specialists in burial customs.

Maybe certain moments in the development of the human race are simply too embarrassing to remember.

Bondeson, God bless him and keep him from having some burial reformer blow tobacco smoke up his anus with a pipe after his departure in order to establish that he is truly dead, has researched his subject to the point of ludicrousness. He ranges with authority from its folkloric roots to its wacky historical applications to its literary texts to its medical realities, and he backs everything up with voluminous citations from obscure sources in most of the major European languages, with a little Latin translation thrown in for good measure. If you are looking for someone who can tell you every article that was in the premiere 1909 issue of the unlamented American magazine Perils of Premature Burial, Bondeson is your man. (An 18th century illustration of a physician engaged in the tobacco-enema diagnosis described above is accompanied by the credit "From the author's collection.") This is a good thing. Some subjects are like bottle-cap collections: Without obsessiveness, without maniacal thoroughness, there's really no point.

Bondeson, a medical doctor and professor at the University of Wales College of Medicine who has written several popular works on medical oddities, says he was inspired to write this book after appearing in an American TV documentary titled "Buried Alive" -- in which, as he cheerfully notes, "my own contribution was filmed in the crypt under the Kensal Green cemetery in London, full of decaying coffins." Bondeson brings a mercifully light touch to his lugubrious subject.

He starts his book by examining what the ancients knew about the medical questions at the heart of his book -- the "signs of death," the physical evidence that allows observers to be certain that life has ended. Like their successors, Bondeson notes that "already in classical antiquity some observers were aware that the criteria of death might sometimes be fallible." Indeed, it appears that in important ways the knowledge of the ancients was comparable to that possessed by many doctors as late as the mid-18th century. Much Greek and Roman medical learning was lost in the Middle Ages, however, and this subject remained singularly opaque for centuries. In fact, physicians did not gain definitive knowledge about the signs of death until this century. Even in the 19th century, many doctors were incompetent at diagnosing death -- to the point where they openly confessed they couldn't tell a dead man from a living one. In the 17th and 18th century, this uncertainty provided grist for the mill of well-meaning alarmists who suddenly proclaimed -- on the scantiest but most lurid of evidence -- that alarming numbers of people were being buried alive.

The most influential of the burial reformers was a French physician named Jean-Jacques Bruhier d'Ablaincourt. Bruhier came upon a 1740 treatise, written in Latin, on the signs of death, written by a Danish-born anatomist named Jacques-Bénigne Winslow, who argued provocatively that "although the modern, surgical tests of death or life were better than the primitive, traditional signs of death used among the people, they were still too uncertain to be relied upon. The onset of putrefaction was the only reliable indicator that an individual had died." The result of this uncertainty, Winslow concluded, was that people were in imminent danger of being buried alive.

To avoid this dread outcome, Winslow recommended a series of measures designed to ensure that the dead were really dead. "The individual's nostrils were to be irritated by introducing 'sternutaries, errhines, juices of onions, garlic and horse-radish' ... The gums were to be rubbed with garlic, and the skin stimulated by the liberal application of 'whips and nettles.' The intestines could be irritated by the most acrid enemas, the limbs agitated through violent pulling, and the ears shocked 'by hideous Shrieks and excessive Noises.' Vinegar and salt should be poured in the corpse's mouth 'and where they cannot be had, it is customary to pour warm Urine into it, which has been observed to produce happy Effects.'"

If the corpse withstood these vigorous ministrations without happy Effects, it was time for Phase 2 -- a Foucault-like regimen in which the well-meaning doctors would literally get medieval on its ass. After cutting the soles of the deceased's feet with razors and thrusting long needles under its toenails, various options were available, including burning the soles of the deceased's feet with a red-hot iron and pouring boiling wax on its forehead. If all else failed, a French clergyman "suggested that a red-hot poker be thrust up the unfortunate corpse's rear quarters." It is not recorded whether this latter method ever revived anyone -- and if it did with what words the awakened individual saluted the attending medical personnel.

Despite these eye-opening details, Winslow's thesis was destined for academic obscurity. But Bruhier, who had his finger on the presumably robust pulse of the reading public, gave it a far wider readership. Not only did he translate it into French soon after Winslow's Latin edition appeared, he jazzed it up by adding a lengthy section of his own in which he cites numerous "cases" which "proved" that premature burial was a serious social problem.

The examples cited by Bruhier in this and his subsequent publications are instructive, for they include many of the archetypal cases of supposed premature burial. For example, he cites cases of corpses that were discovered, when exhumed, to have devoured parts of their own bodies, in particular their fingers -- a grotesque reaction, he and other like-minded reformers were sure, to the victim's hideous discovery that he or she had been buried alive. (In fact, as Bondeson points out, such grisly mutilations, which are found in many apocryphal tales of premature burial, were likely to have been the result of rodents.) He also cites a recurring tale, which Bondeson dubs "The Lady With the Ring," about a woman who was buried with a valuable ring on her finger; when thieves broke in and attempted to steal the ring, the lady would wake up.

Another such tale, "The Lecherous Monk," tells the story of a young monk stopping at an inn who is asked by the grieving innkeeper and his wife to watch over the corpse of their beautiful young daughter. Left alone, the monk "forgot the sanctity of his vows and took liberties with the corpse." His ministrations not only revive the corpse but leave her pregnant; when the monk happens to return to the inn nine months later, she has a newborn baby. He immediately tells the parents that he is the child's father and offers to marry her. They accept the handsome young man's offer with alacrity, even though, as Bondeson dryly notes, he had "confessed, in so many words, to having raped their daughter while he presumed her to be a corpse."

Bruhier promoted such yarns as if they bolstered his case. In fact, both the Lady With the Ring and the Lecherous Monk are folktales, legends found in several different cultures. Their appeal, Bondeson notes, has strong elements of necrophilia and sadism -- which, the reading public's tastes not having changed in 250 years, presumably did not hurt sales of Bruhier's book. With a credulity that one can only regard as deplorable in that pre-"Ally McBeal" era, Bruhier also accepts as gospel various tales then current about "fasting girls" who could live for years without taking nourishment of any kind, as well as incredible stories of people who had survived being underwater for hours, days and even, in one highly fishy case, six weeks.

Bruhier's book was very popular and translated into several languages, including -- crucially -- German. For some reason that Bondeson never explores, the news that people were at risk of being buried alive fell upon the Teutonic ear like a metaphysical dinner bell. For the next half-century, at least, the vaunted "land of poets and philosophers" became the land of carefully arranged corpses, neatly lined up in "waiting mortuaries" staffed with attendants waiting for them to suddenly sit up and ring for help. Not even France was as initially taken with the idea as Germany -- although, in a later development that casts grave doubt on the touted Gallic rationality, the French became obsessed with premature burial just around the time the Germans became aware that they had been sold a coffin full of hot air.

Why did Bruhier's warnings find such receptive ears in the 18th (and later the 19th) century? Why did people suddenly develop a phobia about being buried alive? Bondeson, displaying the sturdy reticence of a slightly snide Dr. Watson, does not presume to leave his area of competence to favor us with his own musings, remaining content to cite the analysis of the great French historian Philippe Ariès. Like most other students of the subject, Ariès argues, says Bondeson, that "the fear of being buried alive was a by-product of the ongoing process of dechristianization. Many people had begun to question the traditional Christian dogma, and secular rationalism left an emotional vacuum for those who had to confront the thought of death without the hope of paradise. This led to an increased fear of death ... The physical torments of a premature burial -- the ghoulish minutiae of gnawed hands, bruised heads, and beaten bodies that recur in Bruhier's books -- may be taken to represent some kind of secularized hell."

This argument seems convincing, especially when combined with the fact that science, which had to fill the void left by God -- in Nietzsche's apropos phrase, it became His gravedigger -- was still in important respects credulous and halting. "In a way, the 1740s were exactly the right time for fears of being buried alive to develop," Bondeson notes; "there was still a good deal of superstition about abnormal fasts, hibernating swallows, and submarine humans, but the rationalist eighteenth-century medical scientists no longer considered these matters to be supernatural." Bondeson also notes that the development of resuscitation techniques, specifically artificial respiration, which was first reported in 1740 (the same year as Winslow's thesis), was crucial in casting doubt on the validity of currently accepted signs of death.

Bruhier's influential books had long-reaching effects, many of them deleterious (or at least expensive and pointless), but they also had several important positive effects. They led to the adoption, in much of Europe, of a waiting period of at least 12 or 24 hours before any person was buried. They also turned legitimate attention to certain causes of death that could lead to unreliable diagnoses. "Bruhier's words of warning that special care be taken with people thought dead from apoplexy, drowning, freezing to death, and 'hysteric passions,' were largely sound," Bondeson writes, noting that this advice "probably saved many people from death, and some from being buried alive." Finally, Bruhier's work changed the entire conception of death, redefining it -- particularly in cases of sudden death, as opposed to slow, chronic decline -- as a medical condition that could sometimes be reversed. As a result, numerous humane societies sprang up, many of them aimed at resuscitating swimmers.

So much for the positive effects. For much of the rest of his study, Bondeson turns to the other effects -- and it is here that "Buried Alive" becomes more and more hilarious. Try as one might to furrow one's brow, make allowances for the limited medical knowledge of the time and feel sympathy for the high-minded intentions of the era's burial reformers, their schemes and rhetoric are so ludicrous, and the mental images they conjure up so ridiculous, that belly laughs ensue.

Bruhier was an ardent advocate not just of the vigorous measures suggested by Winslow to ensure death, but of the aforementioned waiting mortuaries, in which bodies would be "supervised for at least seventy-two hours, or until putrefaction had set in." In 1791, work began on the first such mortuary in Weimar -- a building containing a corpse chamber with eight stretchers, observable by an attendant. (The mastermind of these mortuaries, a worthy by the name of Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland, stipulated that the attendants should be vigorous young men, not the wretched old crones who customarily watched over mortuaries. But Bondeson seems doubtful as to whether this dead-end job was a particularly attractive career choice.) A second such mortuary was built in Berlin, with a new, improved feature: While the Weimar mortuary "relied entirely on the vigilance of the attendant, the Berlin mortuary had a system of strings tied to the fingers of the senseless inmates; these strings were connected to a large bell."

The most aesthetically attractive waiting mortuary, however, was built in Munich. Perhaps in a nod to the delightful tradition of Bavarian song, or in prescient anticipation of the industrial/Goth club scene, this edifice was equipped with a large harmonium, connected by strings to the fingers and toes of the corpses. "Every day, the mortuary attendant played this harmonium to demonstrate it was fully functional," Bondeson notes. "At night, the swelling of the putrefying corpses frequently set off the easily triggered mechanism, however, and the attendant was awakened by a ghostly symphony emanating from the corpse chamber."

The German waiting mortuaries, or Leichenhauser, had a remarkably long run -- most had alarm systems in place through the 1890s, and two in Alsace still had electrical alarms in the 1940s (a push switch was thoughtfully placed in the hands of the corpses when they arrived). Eventually, however, these bizarre, foul-smelling establishments (great floral displays were used to mask the odor of putrefying bodies) went the way of the dodo -- their decline hastened by their expense, by fear of the supposed health hazards resulting from the "mephitic fumes" rising from the corpses and, no doubt, by the inconvenient fact that no reliable report of a corpse coming back to life was ever recorded in any of them.

A simpler solution was the "security coffin" -- a conveyance that would allow the stiff awakening from his dirt nap to stay alive and signal for help. The first such coffin was built for Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick in 1792. It contained a window, an air hole and a lid that could be unlocked. Such a device was too expensive for most people, however, so various cheaper alternatives were suggested. One German parson advocated that all coffins should have hollow tubes connected to them, into which would be placed a rope leading to the church bell. Should a corpse wake up, he would merely pull on the rope, ringing the bell. (Bondeson points out that "the parson's plan did not take into account either the weight of the bell or the feebleness of the poor wretch in the narrow box underneath." This lapse, alas, is not unique to the optimistic parson: Time and again in Bondeson's tale one encounters dubious tales of people who, after being buried alive for hours, days or even weeks, immediately engage in robust and even Olympian physical feats. These Herculean achievements are rendered suspect not only by the decrepitude and weakness customarily associated with people who have been ill enough to have been thought dead, but by the fact that a person buried in an airtight coffin would suffocate after about an hour.)

To rectify this impracticality, another parson (being on the front lines, as it were, parsons were evidently much occupied with the subject) suggested that coffins should be fitted with a speaking tube communicating with the open air. "The local parson should take a stroll through the churchyard every morning and stop by each recent grave to ascertain, through the sense of smell, whether the putrefaction of the body was sufficiently well established to permit the tube to be withdrawn." The tube would also, of course, allow the corpse to yell for help. A similar design made provisions for food and drink to be served through the speaking tube, so that the awakened victim could enjoy a reviving meal while being exhumed. The inventor of this coffin, one Herr Gutsmuth, actually tested his coffin by having himself buried in it twice; on the second occasion, he dined on a clichéd German meal of soup, beer and sausages, after which he delivered a philanthropic speech to the assembled spectators standing above his grave.

But these modest proposals were mere Volkswagens compared to the Mercedes-like heights of luxury offered by some security coffins. Not surprisingly, go-go Americans led the way in opulent security coffin design: Some Yankee designs featured not only flags, bells and lights as signaling devices, but telephones and heaters, as well as supplies of food and wine.

Unfortunately, as Bondeson points out, these admirable contraptions had several fatal design flaws. One problem was the signaling device, which had to be attached to the body in some fashion. Putrefying corpses bloat due to abdominal gas, and the arms and legs also contract; these physiological changes would have set off the alarms. (The movement of the corpse's extremities also explains a phenomenon cited in numerous bloodcurdling accounts of supposed cases of premature burial, which relate in hideous tones how the corpse was found in an attitude of desperate struggle.)

An even bigger problem, in terms of selling them to potential customers, was their excessive reliance on eternally vigilant pastors and sextons. To have real confidence that the security coffin would work, the terrified prospective buyer would have to have confidence that those village worthies really would constantly stroll about the graveyards, listening for ringing bells, watching for waving flags and stopping every few minutes to inhale a copious draught of putrescent gas from a speaking tube. Just one unauthorized break for sausages and beer could lead to an agonizing, worm-eaten death in the bowels of the earth. And what if the mechanism jammed?

Not surprisingly, the security coffin never really caught on. Many fearful upper-class people, especially in England, instead left explicit instructions with their doctors that their corpses be poked, prodded and pierced in various ways to ensure that they were really dead. These techniques included removing the heart, cutting the throat, piercing the heart with a long pin, having all the fingers and toes amputated, and cutting the jugular vein. Taking no chances, the writer Harriet Martineau left her doctor 10 guineas to cut off her head.

The fear of premature burial led doctors to attempt to come up with more reliable tests of death. In addition to the tobacco-smoke enema mentioned above, it was variously suggested that insects be placed in the corpse's ear, that large numbers of leeches be put near the anus and that the nipples be pinched with powerful pincers. Displaying the same unseemly fixation on the tongue that has led to an immoral type of kissing to be given the name of his country, one intrepid French doctor suggested that the tongue of the corpse be "rhythmically pulled for a period of three hours."

England long resisted the Continental dread, but it was invaded by French premature-burial pamphlets in the early 19th century and soon fell prey. The most noteworthy result of John Bull's flirtation with burial reform seems to have been the overheated scribblings of one John Snart, whose "Thesaurus of Horror; or, The Charnel-House Explored" Bondeson describes as "the most ludicrous and gruesome book ever to appear in its particular literary genre." This is a large claim, but the passages excerpted bear it out. Mr. Snart was especially fond of the repeated exclamation mark: "And burst his eyeballs in the vain attempt!!!" "The Baron had been BURIED ALIVE!!!" "He therefore, in a fit of desperation, had dashed his brains out against the wall!!!" "A fermentable mass of murdered, senseless, decomposing matter!!!"

The premature burial scare was introduced into America not by medical science but by popular 19th century writers like Edgar Allan Poe, who was obsessed with the subject, returning to it again and again. The theme is featured in "The Premature Burial," which, thanks to a ridiculous surprise ending, is one of the master's weaker efforts, but also in such masterpieces as "The Cask of Amontillado," with its frighteningly implacable narrator Montresor, who walls up his enemy Fortunato (whose "thousand injuries" we have only Montresor's dubious word for) underground; "The Black Cat," featuring a feline that is buried alive along with a corpse; and "The Fall of the House of Usher," in which the sister of Roderick Usher breaks loose from her premature tomb to doom her brother. Perhaps the subject's most bizarre appearance is in the unspeakably dreadful story "Berenice," in which the strange, dispirited narrator, Egaeus, becomes obsessed with his frail cousin Berenice's teeth. After he learns of her death, he is sitting in his library when a servant bursts in to tell him that Berenice's grave has been violated and her disfigured body found still alive. The servant suddenly points to Egaeus, who is spattered with blood; Egaeus in horror grasps at a little box next to him, which falls to the floor revealing, in one of the most chilling last lines in literary history, "some instruments of dental surgery, intermingled with thirty-two small, white and ivory-looking substances that were scattered to and fro about the floor."

Stories by Poe and others in magazines like Blackwood's spread the creepy gospel far and wide. The leaders of the American burial reform movement were frequently spiritualists whose dread was exacerbated by their belief that the soul could leave the body and wander abroad: How could any signs of physical death be reliable under these circumstances? One of their number, a Dr. Franz Hartman, is perhaps the most terrifying-looking scientist in the annals of medicine -- a maniacal, staring fellow with cavernous rings under his eyes who looks like he just escaped from an asylum for the criminally insane. "There were links also to the proponents of teetotalism and vegetarianism, to the organized spiritualists and quacks, and to the suffragettes and proponents of rational female dress," notes Bondeson, not explaining the connection between the anti-corset league and burial reformers. Obviously, many of the ideas put forward by this odd collection of reformers, who were in the main antiscientific reactionaries, were specious in the extreme, but Bondeson does credit them with pointing out the cruelty of 19th century vivisectionists.

Bondeson concludes his book by asking whether people really were buried alive, and whether they still might be. He pooh-poohs the extravagant claims made by burial reformers (some of whom asserted that one in 10 people was prematurely buried) but notes that there are a few genuine cases on record. During cholera epidemics, in particular, he notes, the risk of premature burial was great. "It must have occurred regularly, but probably not frequently, that living people were buried by mistake," he concludes. As for whether people are still being buried alive, he concludes that they probably are. In third world nations, the risk is greater, but even in Western countries, where legal safeguards exist, misdiagnosis sometimes occurs. He cites cases "of gross incompetence on the part of the attending physician and in several twentieth-century cases of severe hypothermia after intoxication with CNS [central nervous system] depressants." But the risk, clearly, is minuscule.

Throughout his stroll through the rotting byways of his subject, Bondeson has been a rather genial, if reserved, host, but at the very end he plants a nasty Calvinist elbow in the ribs of his readers. Pondering why the fear of premature burial, after a brief revival in the 1970s spurred by the new whole-brain medical criteria of death, has largely faded out, he writes, "Nor is the prevailing present-day lifestyle in the United States and large parts of the Western world, set by egotistical, hyperactive people obsessed with amassing money and luxury goods, conducive to gloomy contemplation of death or fear of a possible life after burial."

Ouch! It's almost enough to make an egotistical, hyperactive, luxury-good-pursuing American feel guilty for laughing his way through this weird and wonderful little tome. But not quite.

Shares