“I have a question,” I shout above the audience, and the question brings the clapping to an abrupt halt. “Do you think I married my father?”

The room goes dead quiet.

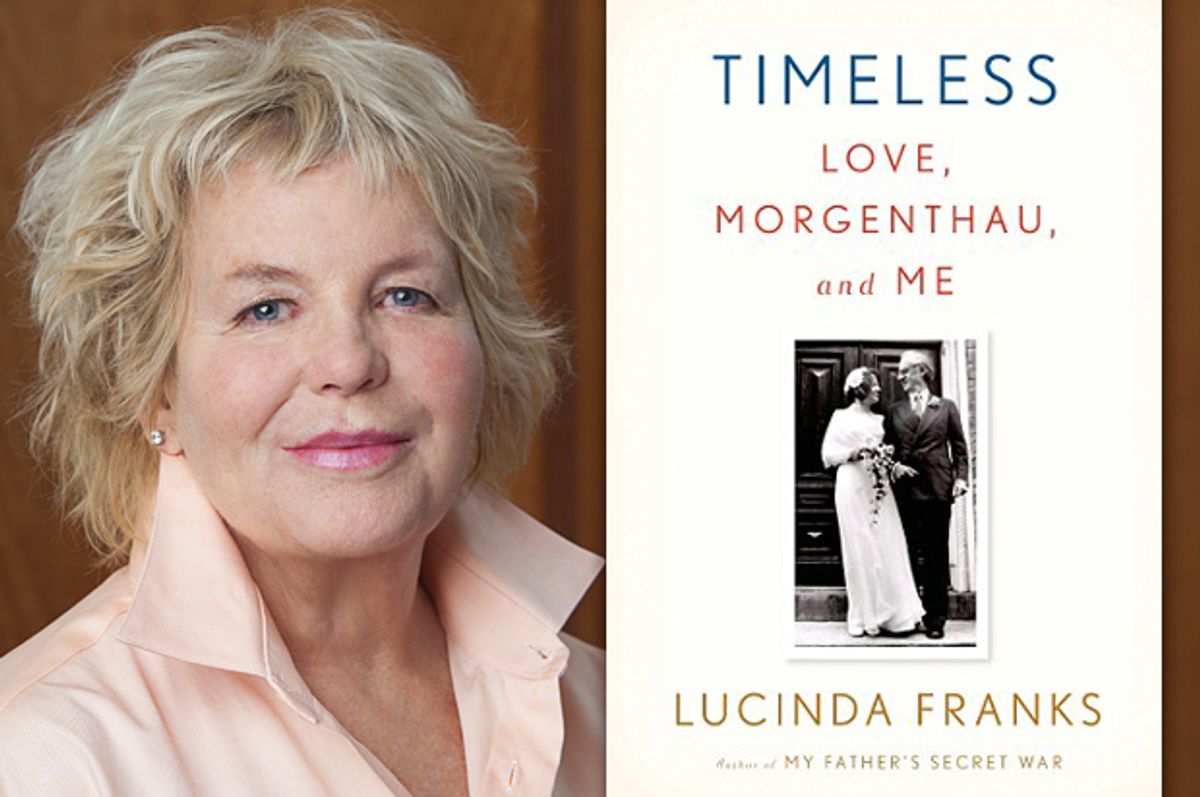

I have been talking for 40 minutes to a social club in Santa Barbara about my new memoir, "Timeless: Love, Morgenthau, and Me." It chronicles my marriage to a man 30 years my senior, a man I had met when he was 57 and I was 26.

The Q and A had ended—or so the audience thought. They certainly didn’t expect this; the author bringing up what was on everyone’s mind but what no one dared ask. Eyes are averted, some gaze at me suspiciously.

How I remember those looks. They came after Bob and I announced our engagement and I imagined the lurid thoughts that were behind them: What’s a young level-headed professional woman doing sleeping with someone old enough to be her father? She belongs in a psychiatrist’s s office (which in the 1970s was as taboo as marrying an older man).

But I had done nothing wrong. Two people of different generations had fallen in love. You can’t choose that kind of thing. Then why had I felt so guilty?

Well, all right, there were some similarities between my husband and my father, but they were superficial at best. Both had voices like bassoons but were sparse of words. Both loved food and ate with excruciating slowness, both were affectionate but not through touch. So I was drawn to the familiar, but who isn’t?

Besides, my father was a Renaissance man. An American spy in World War II, he was chosen for duty because he was a chameleon. He could fluidly shift his physical appearance and learn the skills to rapidly change identities: crack marksmanship, butterfly and moth collecting, bridge, pool, finance, five foreign languages. Ultimately, however, he had become too many people to succeed at being just one. My husband, the prominent District Attorney of New York, was his opposite: so focused he succeeded at one thing after another, from international white-collar crime prosecution to famous law-making criminal convictions.

One day, several years after Bob and I were married, I watched my father go into a grubby diner and empty his pockets so the impoverished folk could get a hot meal. I thought of my husband, who was head of PAL, opening up fire hydrants on a blistering day and grinning as the kids leapt through the water.

The images collided in my mind. I realized the two men were more deeply alike than I thought. My father had been my first teacher; he had laid the path that had led me to the man I married. Bob’s moral values were Dad’s moral values, which were inevitably mine. This made me unaccountably happy.

And sad. Months after his 88th birthday and after learning of his courageous missions in the WWII underground, I lost my father. Losing Bob has always terrified me. Not much younger than Dad, he has mercifully outlived him. Both physically and mentally, Bob is in great shape, but at age 95, for how long?

“Did you marry your father?” someone called out from the audience, emboldened now.

In answer, I picked up my book and read this passage:

How strange and beautiful it is, falling in love with someone who has lived twice as long as I have. I believe that love is no accident, no whisper from a random universe. It comes from deeper channels of longing and recognition: a collection of tiny lights that gathered force long ago. The boy with long fingers sweeping the keys of a piano, an uncle’s laugh, a teacher who always listened. And the one who precedes them all. The father.

The things about him you never forget: his hands circling your waist, flying perilously in the air, sun-blinded, grains of sand rubbing against your cheek; your chubby hand smoothing back the soft bristles of his hair so they spring up again like soldiers.

Then, in a flash, you stand head-to-head, face-to-face. And he walks away, for you have become too mature, too near, a danger... An ineffable longing takes over and then eventually is forgotten.

The years go by, and one day you meet him again—the thistly chin, the bright smile, and, behind his glasses, the love that was always there. He’s not your father, but he is everything you wanted him to be.

Yes, we all marry our fathers. Or men who remind us of them. We look for the traits that we love: a lanky body, a short stocky one, a man who is perennially happy, overtly adoring, or reserved but kind.

And there is a beauty in that. A continuity. A fulfillment.

Sometimes we marry our anti-fathers. If he was cruel or uninterested -- or it could be any one of a thousand unpleasant things -- we look for the person that he was not.

Amid the many other gifts they give us, our husbands redeem what was once lost, help mend the circle of unconditional love that was broken long ago.

We were perfect back then and we are perfect once again.

Shares