As my friend who loves the Coen Brothers' movies said the other night, after we had sat through their latest cool, near-perfect puzzler, "I guess their problem is that basically they don't have anything to say." This is more of a problem for me than for my friend, generally speaking, and I found "The Man Who Wasn't There" -- a loving evocation of the lower-middle-class 1940s noir world of James M. Cain -- a frustrating experience even by Coen standards.

I prefer the Coens in their charming goofball mode, when they structure their all-style-no-substance tributes to movie history around a comic-heroic central figure: Nicolas Cage in "Raising Arizona," Jeff Bridges in "The Big Lebowski," George Clooney in "O Brother, Where Art Thou?"

Seen in retrospect, even my favorite of the Coens' films, the pseudo-profound "Barton Fink," looks more like absurdist comedy than meaningful satire. Mind you, I have no problem with that; the Coens can't resist these deluded and pathetic lunkheads who must confront a ludicrous universe, and their comedies usually provide at least a convincing simulation of warmth and humanity.

I'm much more mixed on the Coens' neo-noirs and imitation genre pictures. I haven't disliked any of their later movies as much as I did "Blood Simple," their very black, much-lauded 1984 debut. But some of the same soulless sadism, the same juvenile-geek urge to out-Hitchcock Hitchcock, resurfaced in "Miller's Crossing" and even later in "Fargo" (redeemed as that was by the performance of Frances McDormand). Of course I understand that for many of the Coens' fans their bravura appropriation of style and sensibility, their amoral mix 'n' match movie-hound aesthetic, is precisely the source of their appeal. Perhaps the reported title of their next project, "Intolerable Cruelty," is meant to tweak weepy old-fashioned humanists like me.

"The Man Who Wasn't There," like "Fargo," is to some extent an effort to bridge the gap between the Coens' comedy and thriller modes. On the surface it's purest formalism: masterful black-and-white cinematography (by Roger Deakins, the Coens' customary co-conspirator), note-perfect character acting and period diction. I mean, these guys pay attention to the friggin' details: When Doris Crane (played by McDormand, who in real life is married to director Joel Coen), the main character's alcoholic and perhaps unfaithful wife, gets drunk at an Italian family picnic, she says the word "goddamn" with the precise inflection of a mid-century woman unaccustomed to cursing. Another character says "the out-of-doors" rather than the more contemporary "outdoors."

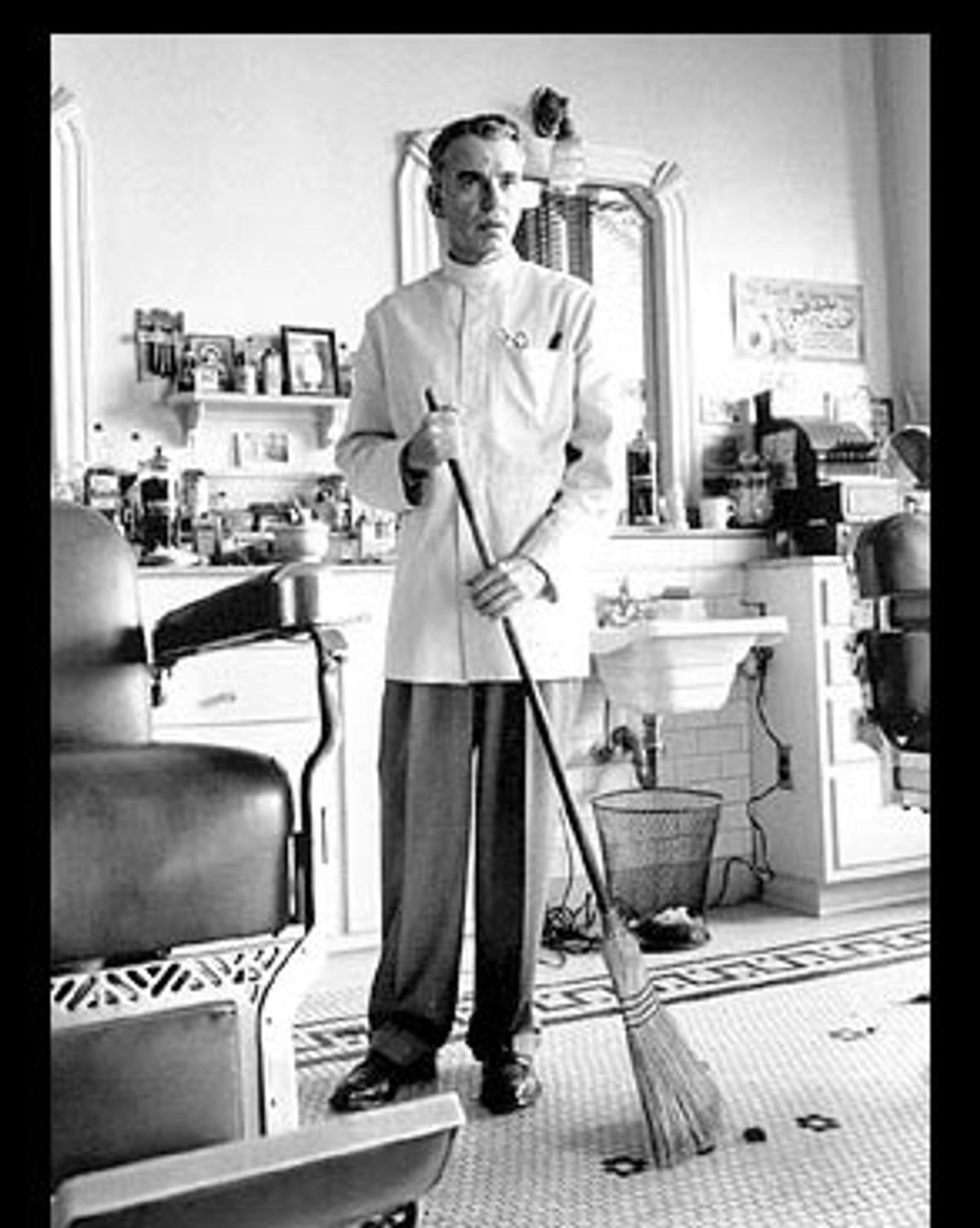

Specifically, "The Man Who Wasn't There" is meant to seem like a companion piece to Billy Wilder's 1944 "Double Indemnity" or Tay Garnett's 1946 "The Postman Always Rings Twice" (both based on Cain novels). We've got a tangled web of family money, unhappy marriages, stifled dreams, greed, adultery and murder. In Ed Crane (Billy Bob Thornton), the small-town California barber whose misguided attempt to escape his lot in life ignites the drama, we've got a narrator-protagonist so inscrutable that the more he talks the less we really know about him.

This is the point of the film in some ways: No one can ever remember Ed's name or place him in context; when he does something bad he gets away with it, and the things he gets blamed for he didn't do. But this sure doesn't make it any easier to like or understand Ed. Like so many other Coen characters -- and, it must be said, so many characters in classic film noir -- he seems like a laboratory animal trapped in a cage of elaborate and beautiful construction.

With his rugged face photographed to accentuate its creases and jowls, Thornton certainly possesses the correct look -- handsomeness edged with middle-aged decrepitude -- for this part; he suggests Montgomery Clift crossed with the young Boris Karloff. Ed cuts hair every day in the Santa Rosa, Calif., barbershop owned by Doris' motormouth cousin (Michael Badalucco, well known to viewers of TV's "The Practice"), but a chance encounter with a customer (Jon Polito, a Coen regular) gets him thinking about bigger things. Or anyway about dry cleaning. (Santa Rosa, by the way, is probably not a random choice; it was the setting for Hitchcock's "Shadow of a Doubt," whose powerful claustrophobia is echoed here.)

Typically, the Coens (Joel directs, Ethan produces and they co-wrote the screenplay) want to worship at the altar of classic Hollywood and also send it up mercilessly. Late in Ed's running voiceover, when everything has gone irreparably wrong for him, he reflects that he is indeed guilty: "Guilty of living in a world that had no place for me. Guilty of wanting to be a dry cleaner." This awkward, melancholic mix of the poetic and the pathetic seems to be exactly what the Coens are after in "The Man Who Wasn't There," and all I can really say about that is that they achieve it wonderfully and I can't for the life of me see what the point is.

Ed needs $10,000 to invest in scam-artist Polito's dry-cleaning franchise and decides to get it by blackmailing Big Dave (James Gandolfini), who runs Nirdlinger's department store. Big Dave and Doris, who keeps the books at Nirdlinger's, may be having an affair, but Ed and Doris' marriage is something more delicate and difficult than the typical film-noir straying-wife scenario. Their relationship is sexless but still tender, as a lovely, near-wordless scene in which Ed shaves her legs in the bathtub displays. Doris may be a vain and damaged woman, pathologically laden with undergarments, cosmetics and high-style accessories, but in McDormand's admirable hands she is never a cartoon bitch.

Gandolfini (who plays TV's Tony Soprano) doesn't do anything special here, but the Coens are of course exploiting our sense that any character he plays is the last person in the world one should try to blackmail. Indeed this episode leads to a hair-raising homicide (by cigar trimmer) and various ensuing complications that require the services of the finest and most expensive defense lawyer in California, sharp-dressed Freddy Riedenschneider (Tony Shalhoub).

But the heart of "The Man Who Wasn't There" -- if it indeed has one and not just a set of inadvertent nervous twitches -- doesn't lie in Deakins' marvelous shots of apartment-house hallways and department-store interiors, or in lines like "This could be your dolly's ticket out of the death house!" The film also offers a half-coherent sense that Ed is striving after something much bigger even than dry cleaning, some transcendence or metaphysical understanding. Ed is a barber who sees hair growth as a mystical force, who appears to encounter extraterrestrials, who develops a (mostly) innocent infatuation with Birdy (Scarlett Johansson), the piano-playing teenage daughter of an old friend.

As Riedenschneider says when invoking Heisenberg's uncertainty principle to bewilder a jury, "They got this guy in Germany named Fritz. Or maybe it's Werner." What makes me respect "The Man Who Wasn't There" despite myself is the sense that the Coens want it to be about something that can't be described or defined, even by Fritz or Werner. By the end of Ed's story he wants to rebuild his destroyed marriage and tell Doris things he never could before, and it almost seems like the same can be said of the movie: It wants to break out of its aesthetic prison and tell those of us out there in the audience something precious and impossible. In both cases it's a nice try but a bit too late.

Shares