Strange things happen in this world, and the fact that the film "Kandahar," by the Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf, is now likely to find a substantial international audience is a small but genuinely strange byproduct of recent history. A year ago "Kandahar" would have been a footnote on the movie-release calendar, noticed only by hardcore film buffs and human rights activists. It's a semi-documentary drama, shot in and around a refugee village on the Iran-Afghanistan border. It has no professional actors and was largely improvised; according to Makhmalbaf, many of the performers he recruited had never seen a film.

But to explain the circumstances under which "Kandahar" was made is not to explain its essential nature. This isn't artless, earnest ethnographic documentary (which is itself a kind of fiction, although that's another story). Often a strikingly beautiful meditation on the harsh desert landscape it surveys, "Kandahar" is also an enigmatic and possibly allegorical fable about a lone figure on a dangerous journey, and so belongs to what may be the oldest storytelling tradition in existence. The fact that this lone figure is a woman, voyaging into the quasi-medieval nightmare of Afghanistan under the Taliban, makes clear that Makhmalbaf's artistic vision is traditional and radical at the same time.

To a large extent, the genesis of "Kandahar" lies with its "star," a Canadian journalist named Nelofer Pazira, whose family left Afghanistan in 1989, when she was 16. In the late 1990s Pazira tried to reenter Afghanistan through Iran, in hopes of finding a childhood friend whose letters about life under the Taliban regime had grown increasingly desperate. She contacted Makhmalbaf, one of Iran's leading filmmakers, to ask for help, partly because his 1987 film "The Cyclist" had sympathetically portrayed the plight of Afghan refugees. He could do nothing to get her across the border; instead, like any good artist, he seized the material that life presented him.

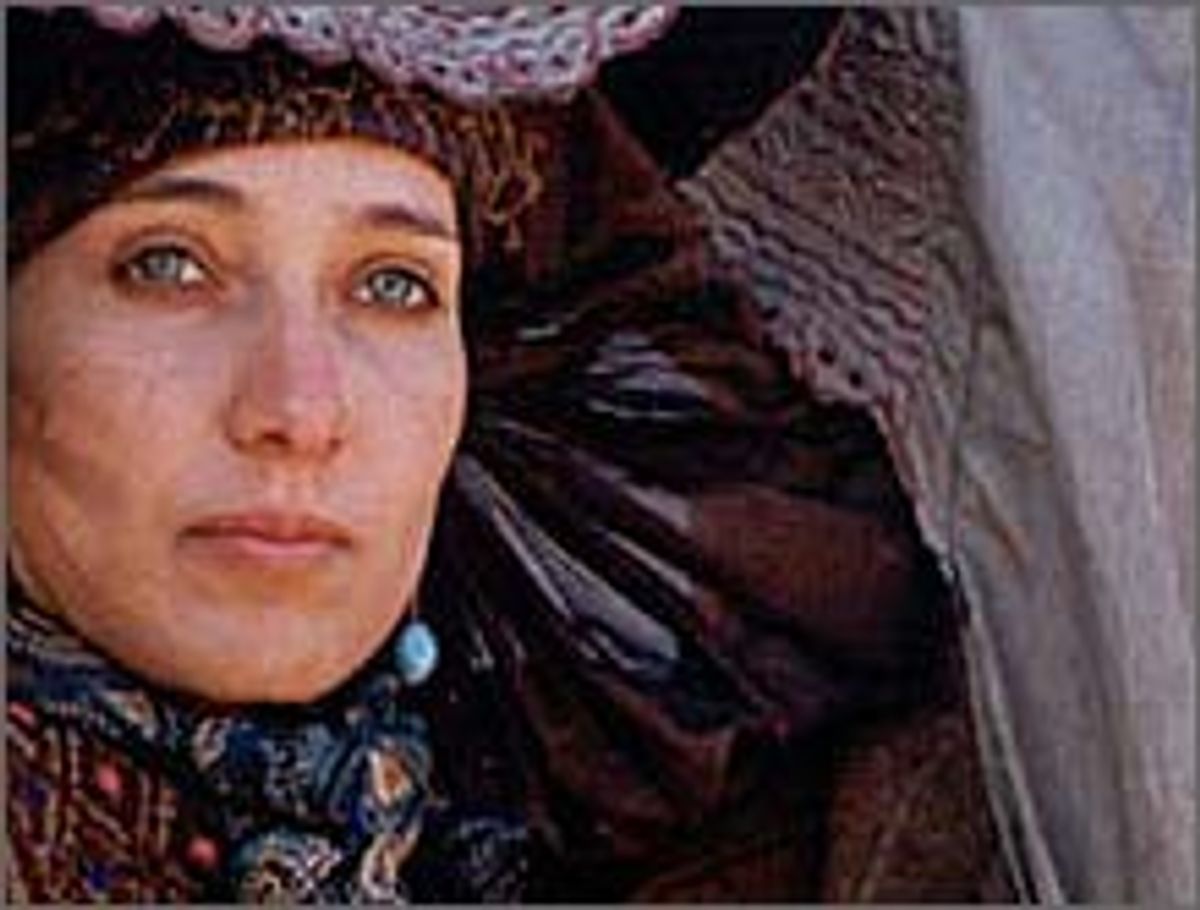

Whether the point of "Kandahar" is ultimately political or aesthetic is a complicated and, I suspect, irrelevant question. On one hand, Pazira is a striking beauty with a wounded, almost distracted air, a fact Makhmalbaf has clearly not missed. On the other hand, the odyssey of Nafas (the character Pazira plays), who must don the burqa for her journey through Afghanistan, provides heartbreaking testimony of the devastation the entire country has undergone, and the bitter ordeal of its women.

Like the other Iranian directors who have come to the film world's attention in recent years (including Majid Majidi, Jafar Panahi and the inimitable Abbas Kiarostami, probably that nation's answer to Bergman or Kurosawa), Makhmalbaf is not much concerned with Hollywood-style notions of pace and narrative. For some time, "Kandahar" seems to be mired in extended ruminative passages during which Nafas speaks to her tape recorder in English, dictating lyrical letters to the sister she hopes to rescue in Kandahar. (The sister lost her legs to a land mine and was left behind when the family fled the country, and has written to Nafas that she plans to kill herself.) Then, abruptly, things begin to happen.

Nafas crosses the border disguised as the fourth wife in a large Afghan family that packs itself into a golf-cart-size truck for the trip to Kandahar. They get nowhere; the family, understandably, is more interested in picnicking in the desert than in the long and uncomfortable journey. Almost casually, bandits steal the truck and all the family's possessions. Left with nothing, the husband takes his three real wives and their children back toward Iran, leaving Nafas stranded in a place and time where a woman alone has a status somewhere between a livestock animal and a criminal.

This is an inherently dramatic, not to say terrifying, situation, and some viewers are likely to be frustrated by Makhmalbaf's refusal to hurry the film along. Nafas is unquestionably in grave danger, but part of the film's point is to convey a sense of Afghanistan as a place where time and history do not matter, or at least not in the same way they matter to us.

Similarly, the film's half-accidental, naturalistic method is used to discover a reality that seems uncannier than any fiction. Nafas meets a small-town "doctor" who turns out to be an American black Muslim whose spiritual quest has ended in doubt and disillusion. In turn, they encounter two Red Cross workers from Eastern Europe, who spend their days bickering with the limbless clientele of their prosthesis clinic.

Nafas' various traveling companions are transitory and never quite trustworthy: a small boy, kicked out of an Islamic school, who steals jewelry from the dead; a man who is missing an arm but trying to sell two prosthetic legs; the mysterious American, who may be falling in love with her. She undertakes the final leg of her journey concealed as a member of an oddly mournful wedding party, a horde of burqa-clad women (and, curiouser and curiouser, one man in drag) heading for the city of the Taliban. At that moment she seems as lost and as doomed as the American woman abducted into servitude at the end of Paul Bowles' "The Sheltering Sky."

Even that comparison is instructive; it may surprise American viewers that an Iranian Muslim sees Afghanistan as an isolated and backward place where the 20th century made only a few scattered and almost surreal impressions. But it's high time we understood the immense cultural difference between those countries. (Makhmalbaf, in fact, wrote and produced "The Day I Became a Woman," one of the frankest films about Iranian women to date; it was directed by his wife, Marzieh Meshkini.) It's also time we understood that, despite the richly deserved defeat of the Taliban, B-52s and Special Forces troops will not be enough to alter the confounding realities of Afghanistan.

Shares