Most Olympic events have some tenuous connection with a useful human activity. Running fast and jumping far need no explanation, but even the more apparently gratuitous sports could come in handy. Being good at water polo, for example, would be a plus if a gang of thugs in bathing suits suddenly jumped into your swimming pool and tried to make off with your pool toys. Curling, with its mysterious frenetic ice- sweeping, could be valuable preparation for those planning to become Eskimo housewives. And knowing how to fence would be invaluable should you be a loudmouthed, adulterous scoundrel who somehow found himself in early 19th century Heidelberg.

But the pole vault? Who first dreamed that up? Some addled medieval military strategist, hoping to send a phalanx of unfortunate warriors flying over the enemy's castle walls? A manufacturer of 15-foot-long wooden sticks, trying to grow his business? No explanation seems to make sense: The pole vault, like the ski jump, is apparently just one of those sports that exists for its own sake. And that makes it all the more marvelous.

I'd seen pole vaulting in Sydney, when American woman vaulter Stacy Dragila won the gold, but I was on the wrong side of the stadium and it was a little hard to stay involved. One thing that people who have only seen the big Olympic track and field events on television may not realize is how chaotic and hard to follow things can be when you're actually there. This is partly because of the size of the stadiums (huge), but also because many events happen at the same time. This leads to strange juxtapositions, and double dramas unfolding simultaneously. For example, last night's glamour event was the men's 1,500 meters, in which Morocco's Hicham el-Guerrouj, a four-time world champion and perhaps the greatest middle-distance runner of all time, was trying to end his Olympic nightmare: El-Guerrouj has lost only four times in eight years, but two of those were at the last two Olympics. Going in, if you had told me that I would take my eyes off that race for one of the 214.18 seconds it took to run it, I would have laughed. But I was so deeply engrossed in the drama unfolding in front of me that I had to turn away from the el-Guerrouj saga for a few seconds.

The drama was the women's pole vault final, and it came down to a three-way duel between Russia's Yelena Isinbayeva, Russia's Svetlana Feofanova and Poland's Anna Rogowska. In a shocking development, defending Olympic champion Dragila, who later blamed too-tight shoes for giving her problems with her Achilles tendon, did not even qualify, failing to get over a rudimentary 4.40 meters. Her debacle took place on the far side of the stadium Friday night, unnoticed by the crowd. I realized she had gone out, but I was watching something else and didn't see her final miss, or her reaction. The huge, buzzing stadium resounds with blazoned deeds, with joy and heroism, but at the same time it is filled with invisible heartbreak, enormous personal losses that go unseen, like the tiny figure of Icarus plunging into the distant sea in Breughel's happy pastoral painting. This is one of the many ways in which neither the Olympics, nor human beings, have changed.

The pole vault competition takes hours. Every competitor is given three chances at a given height; they're gone if they miss the third. The competition was wide-open until 4.65 meters, when the challengers -- notably Poland's Monika Pyrek and Iceland's Thorey Edda Elisdottir -- crashed and burned. (The departure of the latter, who combined impossible height, granitic abdominals, broad shoulders and a blond Viking face that Beowulf would have given away all his rings for, sent deep gloom through those men petty-minded enough to root, in part or in whole, on the basis of such superficial phenomena. I do not myself know who these men are, but unless they can demonstrate that they can use them responsibly, their binoculars should be taken away.)

That left the big three, who would divvy up the medals between them. First up was Poland's Rogowska, with the bar set at 4.70. She soared over and jumped for joy: If the Russians faltered, she could take home a gold that no one expected. But Feofanova was not going to falter. The red-haired, freckled, fair-skinned former gymnast has toughness written all over her, and her form is as consistent as a machine. You'd pass her on the street and not even notice her, but she has ice water in her veins and will beat you at anything she wants to beat you at. She went over 4.70 easily.

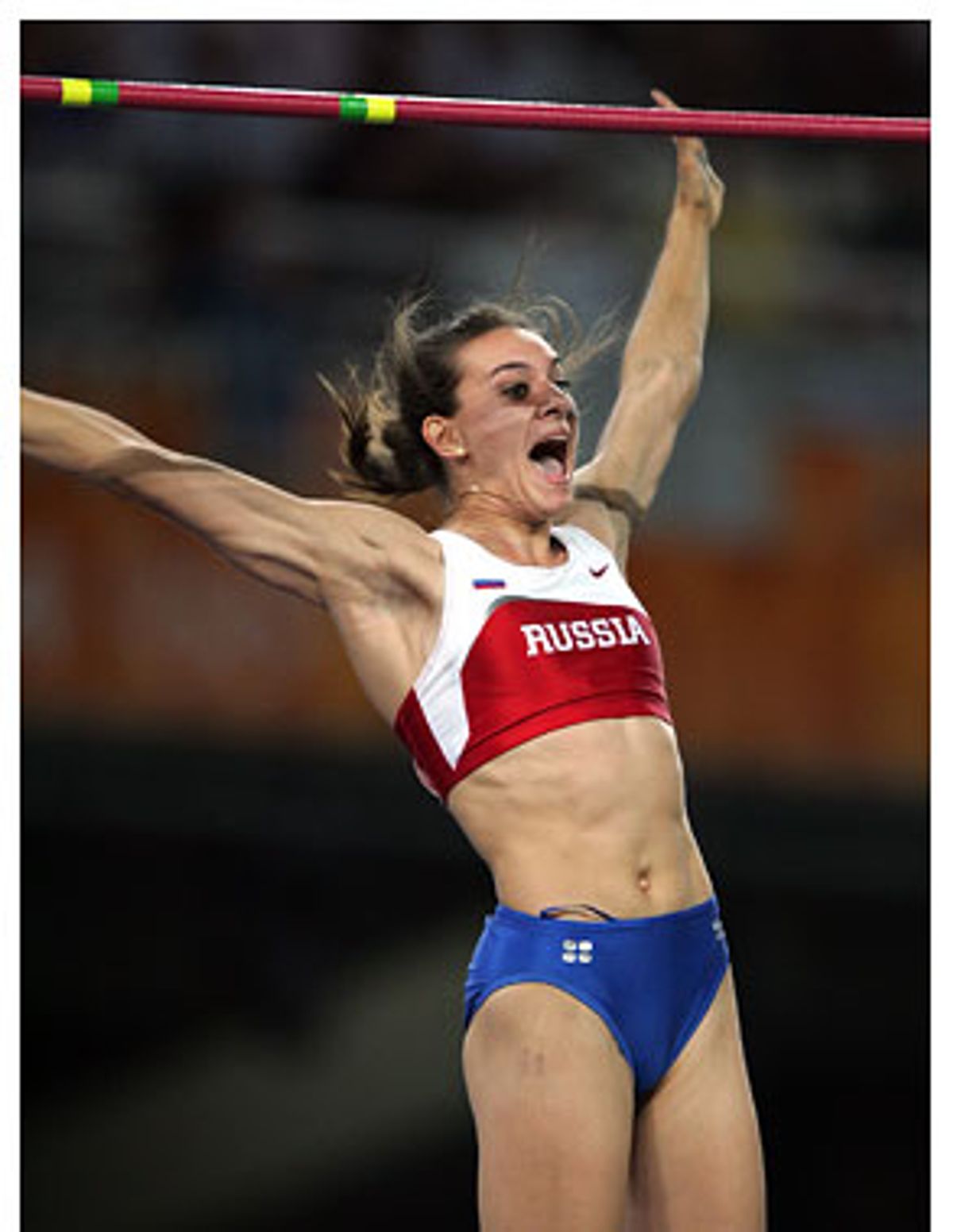

Now it was Isinbayeva's turn at 4.70. Dark-haired, flashing-eyed and Slavic-featured, with a superbly elegant, muscular physique, she was the current world record holder, although that didn't mean much. She and Feofanova had been trading world records like baseball cards all summer long: She set the last one, 4.90, only a month ago. She set out on her run down the track, powerful, light-footed, holding the absurdly long pole upright, made the crucial stick plant (the right hand grip at the moment of the plant seems all-important), exploded into that ridiculous breathtaking elevator-going-up swing feet-first into the air, soared up while twisting, easily cleared the bar -- and somehow hit it coming down. As the bar landed in the pit behind her she jumped up and was seriously pissed. Her eyes shot out flames like a T-34 tank. I've watched a lot of dear old Svetlana Khorkina, the most famous of temperamental Russian athletic divas, but trust me, even Khorkina doesn't shoot off sparks the way Isinbayeva did right then.

Now Rogowska put the bar up to 4.75. She missed. Feofanova then missed fairly badly. (One of the intriguing things about pole vaulting is how many ways there are to miss, from mis-hitting your plant to not getting enough vertical lift off the plant to misjudging the horizontal distance to the bar to not clearing your arms as you go over. Many times, vaulters never even get the pole down after their run.) Isinbayeva opted to pass a second jump at 4.70, so she now was making her second at 4.75. If she missed this, she would have only one more chance. She missed. Anger now began to turn to despair, almost tears. She looked imploringly over at her coach, sitting across the track.

Rogowska missed at 4.75 but Feofanova sailed over. Rogowska missed again. She was out but sitting on a silver medal unless Isinbayeva could come back. She looked ecstatic: Silver would be beyond her dreams. She could barely contain herself, she was so excited.

And then Isinbayeva made one of those gambles that make sports so much fun to watch. She had missed at 4.70 and 4.75 but elected to pass her final jump at 4.75 and put the bar at 4.80. If she missed, she would only take a bronze. If she made it, she would vault into the lead. In Vegas, they call it doubling down.

She stood at the end of the runway, her lips moving, saying something to herself. She was ready. She rocked on her feet and began the run, the crowd roaring for her. The stick, the ascent, hydraulic -- perfect -- twist, over! As she cleared the bar, maybe before she cleared it, even before her arms were clear of it, at that very moment she opened her mouth and screamed with joy. It was a vision I'll never forget because it happened when she was still in her jump. As she flew over and down, the bar motionless, a giant jolt of electricity ran through the crowd. She leaped up, and if you want a visual embodiment of the word "passion," it was on her face.

But she still had Feofanova to contend with. The two passed inches away but did not look at each other. They have acknowledged that they're not exactly bosom pals, with Isinbayeva saying they have a "hi and goodbye" relationship. Feofanova was now vaulting at 4.85. Isinbayeva sat against the athlete's bench, her back to the bar apparatus, with a huge towel over her head. Feofanova prepared, weighed, ran, planted, jumped -- and missed. Now Isinbayeva was not just back from the dead, she was in full and devastating form. She nailed 4.85, with the crowd in full voice.

It was Feofanova's last chance. She chose to take her last vault at 4.90, the world-record height. She missed and it wasn't particularly close. She lay on her back for a moment, then jumped up and waved to the crowd, which gave her a warm ovation.

But Isinbayeva had one more vault. She set the bar at 4.91, higher than any woman has ever vaulted. As she lay on her back, preparing, the camera found her and for the first time she smiled. The gold was in the bank. This was strictly for glory.

The crowd wanted both and she did too. Down the track she ran, toward the bar that rose more than 16 feet up -- three times her height. She planted the stick and uncoiled and the chrysalis thing happened again, the metamorphosis, an ungainly spear-carrier somehow turning first into a wrestler, then a gymnast, and finally into a bird. She went over, and when she came down, she collapsed for a moment and bounced back up, her face ablaze with half-disbelieving joy, and then the tears came.

Later, after the crowd had mostly disappeared, a kind-faced, middle-aged man came over and hugged, congratulated and spoke to her; it seemed like family, his calm demeanor expressing that I'm-proud-of-you-but-everything's-still-the-same feeling that the greatest celebrities must come to crave like water. Feofanova then came over and the two exchanged a hug, and I got a good long look at Foefanova's face with binoculars (being used for legitimate journalistic purposes), and that was a real, warm smile. So there were two champions there.

A lot else happened last night. Roman Sebrle of the Czech Republic won the men's decathlon, earning the title of world's greatest athlete by beating out an inspired effort by the U.S.'s Brian Clay. (The procession of the male decathletes around the track is something everybody should see, male, female, straight or gay -- these are the most beautiful male physiques, quite simply, in the world. And that's saying something after watching the procession of bodies here, which is pretty awe-inspiring. They look like they average out at about 6'1", 190, with superbly balanced musculature. They're bodies designed and honed to do everything. Stunning. But not worth becoming a decathlete to achieve.) American sprinter Joanna Hayes roared to victory in the 100 hurdles, as the Canadian favorite, Perdita Felicien, crashed on the first hurdle and immediately collapsed, grimacing in despair and bitter disappointment, knowing one misstep had blown her chance. Tonique Williams-Darling of the Bahamas won a stirring women's 400 meters, beating the great Mexican quarter-miler Ana Guevara and deflating the hopes of the numerous Mexican fans who turned up in huge sombreros and Mexican flags. Williams-Darling, who has an extraordinarily beautiful and sensitive face, won the prize for most heartfelt comportment on the medal podium.

And finally, there was el-Guerrouj. Everyone was pulling for him, an atmosphere that can seem ominous. He ran a smooth race, holding a perfect outside position until he made his move to take the lead midway through the race. He was leading coming out of the last turn, but on the home straight his great rival, Kenya's Bernard Lagat, kicked hard and overtook him. There was no way of knowing what would happen, no form to read, the challenge was too formidable. As they burned neck-and-neck toward the finish, with the crowd standing and imploring, the Moroccan reached down and summoned what was in him. It had not been enough at the Olympics before.

This time it was. He retook the lead and held off Lagat for the agonizing last 30 meters. When he crossed the line, 12 one-hundredths of a second ahead of the Kenyan, and realized he had won, he fell to the ground and kissed it, in prayer, in thanks. Lagat ran over and embraced him, a sportsman in every sense of the word, seeming to take almost as much joy in the victory, in the lifting of the curse, as his rival.

Guerrouj, too, cried as he ran his victory lap around the stadium. "It is finally complete," he said later. "Four years ago in Sydney, I cried with sadness. Today I cry tears of joy. I'm living a moment of glory."

And as el-Guerrouj ran around the great arena, his face radiant with joy, we cheered, we laughed, and we too gave thanks to the god, the force, the spirit that rewards a champion.

Shares