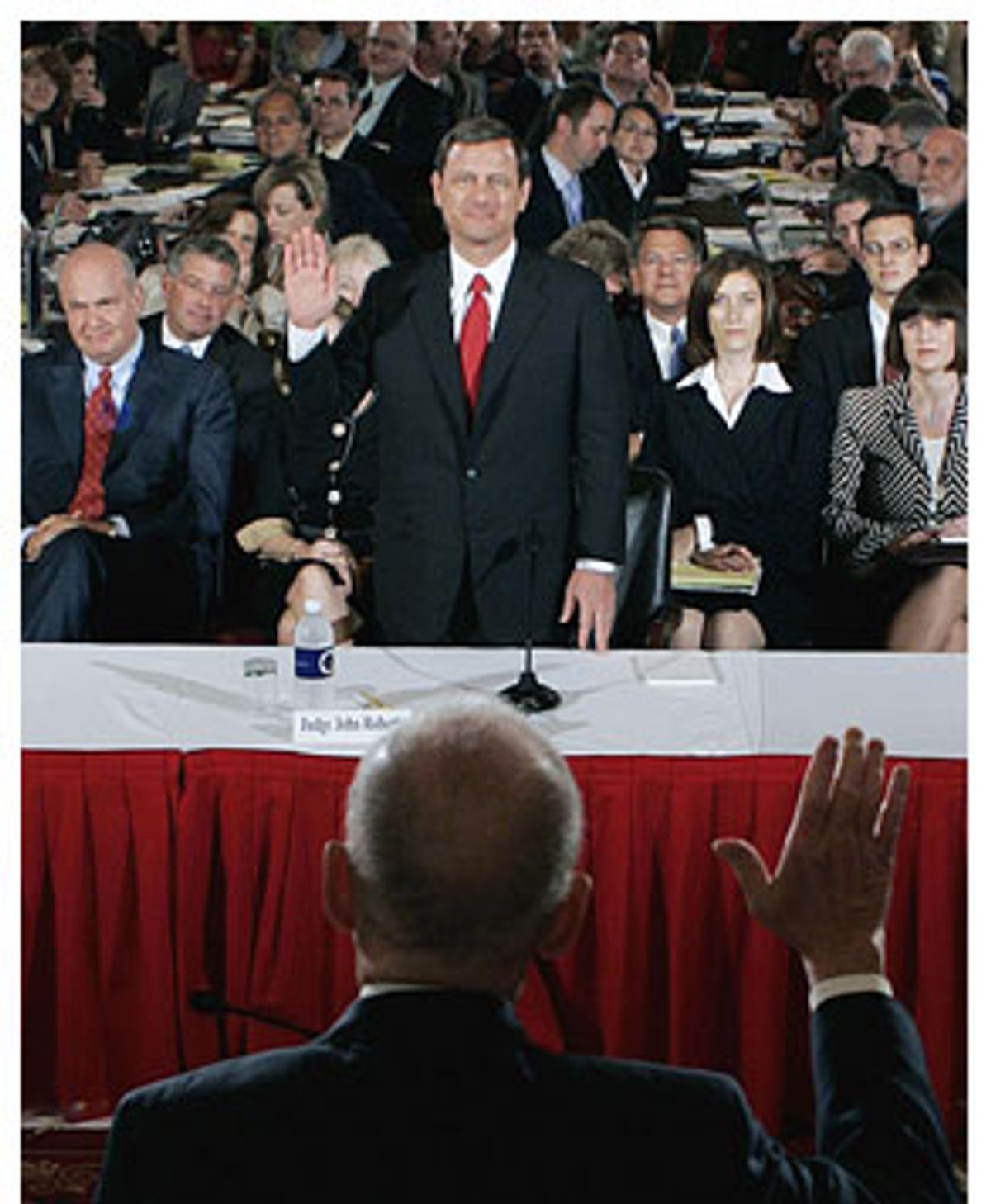

At some point in August, Judge John G. Roberts Jr., President Bush's nominee to head the U.S. Supreme Court, appears to have found time to tan. He entered the Russell Caucus Room Monday for the first day of his confirmation hearing with his face glowing in an even bronze tone, a striking feature in a room of uniformly pasty white men and women. His skin contrasted with his starched white collar, his charcoal suit and his cherry-red power tie. It made his smile gleam. "You are obviously very talented," Sen. Russ Feingold, D-Wis., told Roberts once the hearing got under way. "And you also look healthy."

To complete the visual package, Roberts brought with him some of the cutest kids the Senate has seen, two blond cherubs, 4-year-old Jack, who wore a gray bow tie, and 5-year old Josie, in a white headband. Then he delivered the hearing's most memorable line, a sports simile intended to answer the large outstanding questions about his judicial temperament and ideology. "Judges are like umpires," Roberts told the Senate Judiciary Committee, in an opening statement delivered from memory. "I will remember that it is my job to call balls and strikes, and not to pitch or bat." Like Roberts, the line sounded good, but that was all. It provided no actual insights.

That said, the first day of Roberts' confirmation hearing went well for the nominee, even as it proved to be a practice in platitudes, a four-hour spectacle of partisan posturing and public introductions in a marble hearing room gilded with gold and strung with chandeliers. Senators droned on, while Roberts posed for the camera. Republican and Democratic senators both praised Roberts' sterling reputation, but that was where their agreement ended.

For Democrats the coming days and weeks of hearings are a chance to crack the handsome shell of Roberts, to find out how he thinks and what he would do to the nation's highest court. Roberts, they warn, might lead the country backward, to a time when the courts did not protect the powerless against the will of the powerful. "In particular, we need to know his views on civil rights, voting rights and the right to privacy," said Sen. Edward Kennedy, D-Mass., "especially on the removal of existing barriers to full and fair lives for women, minorities and the disabled."

By contrast, Republicans argued that the coming hearings -- which will start with questions tomorrow -- should be an extended exercise in evasion. One by one, Republican senators cited judicial ethics rules and historical precedent to explain why the American people should not expect to hear anything of substance from Roberts before he becomes the chief justice, a position Democrats have taken in the past to protect their own nominees. "Some have said that nominees who do not spill their guts about whatever a senator wants to know are hiding something from the American people," said Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, who called that notion "false." "The Senate traditionally has respected the nominee's judgment about where to draw the line."

Committee chairman Sen. Arlen Specter, R-Pa., aptly observed that Roberts' willingness to describe his own views over the coming days will depend less upon any constitutional duty than his own fear of rejection by the Senate. "Nominees answer about as many questions as they think they have to, to be confirmed," Specter said in an ad lib that was not in his prepared statement. "It's a subtle minuet." If that rule holds true, the coming days are sure to be frustrating for Democrats. Barring an unforeseen revelation, Roberts is widely seen as a shoo-in for confirmation, creating an imbalance between the huge stakes of his nomination and the piddling suspense it has generated. As several senators observed, Roberts is only 50 years old. If confirmed as chief justice, he may place his mark on American law for 30 or 35 years.

But Democrats are not the only ones uncomfortable about the relative dearth of information on Roberts' legal views. Away from the microphones during a recess, Sam Brownback, R-Kan., said he would prefer it if Roberts just came out and stated his opposition to Roe v. Wade, a case that Brownback blames for the death of 40 million unborn children. "It creates some unease," Brownback said of Roberts' unknown position on the case. "I would like to know."

On the other side of the aisle, Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., said she also would like to know where Roberts stands on issues concerning women's right to choose. "It would be very difficult for me to vote to confirm someone to the Supreme Court whom I knew would overturn Roe v. Wade," she said. "I remember -- many of the young women here don't -- what it was like when abortion was illegal. I knew a woman who killed herself because she was pregnant."

After the hearing ended, the senators walked out into hallway to spin the day's events. The spin sounded remarkably like the hearing itself, which will continue at 9:30 a.m. Tuesday in a less resplendent room. "On the other side of the aisle, Judge Roberts was counseled to say as little as possible over and over again," said Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., in protest. Nan Aron, of the Alliance for Justice, stood nearby speaking of a new letter that Democratic senators had just sent to President Bush asking for more documents from Roberts' tenure in the Justice Department. Asked if she thought judges should "pitch or bat" instead of just "calling strikes," she only laughed.

Ed Gillespie, the lobbyist-turned-Republican National Committee chairman, who is guiding Roberts through the confirmation process, stood nearby, outside the men's room. Asked how he thought the first day had gone, he offered this non sequitur. "When you see someone give an opening statement without the benefit of a single note -- he had a blank pad in front of him," Gillespie said, "it is clear that this is someone who is a very fair, even-handed, open-minded judge."

There was also a pro-life activist in the hallway, Merrie Turner, wearing a period costume from 1776. She said she was dressed as Betsy Ross, the woman who had sewn the first American flag. When she came in the building, her corset had set off the metal detector. "I just believe that President Bush has made a good selection," she said of Roberts, though she acknowledged she had no evidence concerning Roberts' stand on abortion. "He is simply a good judge."

Shares