Once upon a time, before hapless couples tortured each other by frolicking with beautiful "singles," before a naked, ruthless corporate trainer won a million bucks for outscheming 15 opponents in the South China Sea, before "The Mole" and "Big Brother" and "Who Wants to Be," or "Marry," or barbecue, or whatever, "a Millionaire," before Oprah and Jerry and Maury and Ricki, even before we found out what happens when people stop being polite and start getting real, there was "The Dating Game."

Quaint and gentle by today's standards, with its Herb Alpert theme music, giant daisy set decorations and double-entendre-laden interplay between bachelors and "bachelorettes," "The Dating Game" went on the air in December 1965 and was the first success of a producer named Chuck Barris, who had an idea whose simplicity belies its genius: People will do anything to get on TV, and other people will watch them.

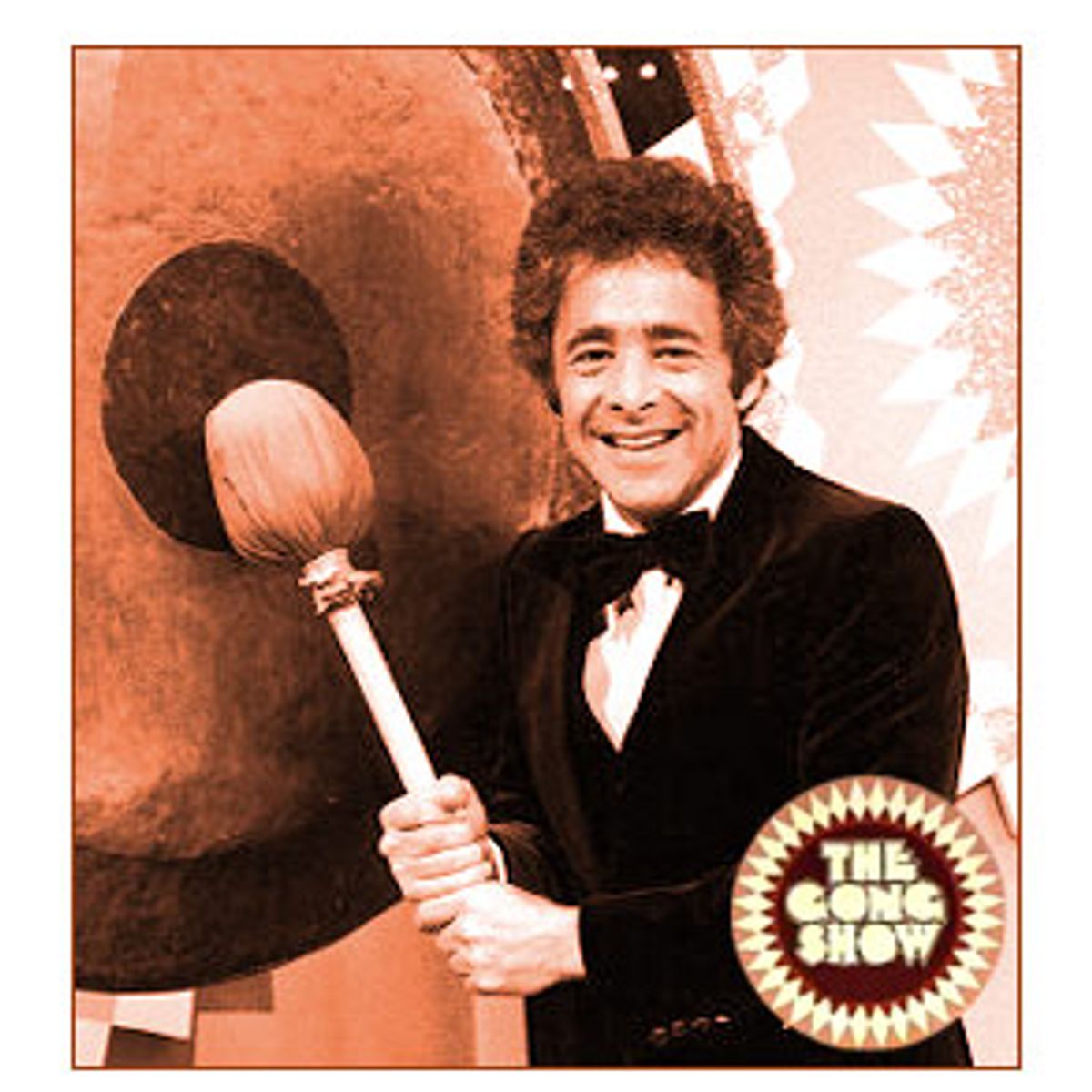

Thirty-five years later, that idea dominates television. Chuck Barris, the King of Schlock, the Baron of Bad Taste, the Ayatollah of Trasherola, remembered now mostly as the loopy, squinty-eyed host of "The Gong Show," is the godfather of reality TV.

"Game shows have always operated on the premise that ordinary people are the stars of the show," says Steven Stark, author of "Glued to the Set: The 60 Television Shows That Made Us Who We Are Today," "but he raised it to an art form in the sense that you don't just show ordinary people in favorable circumstances -- you may do badly on a quiz show but you still look OK anyway -- but you can humiliate them and they'll still go on, for their 15 minutes of fame or whatever."

Barris didn't just introduce humiliation to daytime TV. "The Dating Game" and its 1966 companion, "The Newlywed Game," were among the first shows to acknowledge that people actually have sex. And they were game shows based on exploring human relationships, rather than simply answering general knowledge questions or solving puzzles. And the prizes were modest -- a restaurant dinner, a new washer and dryer. The real prize wasn't a big cash payoff, it was being on TV in the first place. "There wasn't a need for big prizes," Barris wrote about "The Newlywed Game" in the first of his two autobiographies. "The possibility of being on coast-to-coast television was tempting enough to lure the newlyweds to our studios."

"Music changed when the Beatles arrived," David Schwartz, the editor of the Encyclopedia of TV Game Shows, told Entertainment Weekly in 1999, "and game shows changed when Chuck Barris' shows came on."

Barris also changed the industry behind the scenes -- an accidental innovation that's had an even greater impact on television than his on-screen successes, and will continue to do so long after the reality craze fades, if it ever does. When one of his shows, "The Parent Game," was dropped from the NBC schedule before the first episode aired in 1972, Barris bought back the pilot and sold the show to local stations one at a time. Thus was born first-run syndication, a multibillion-dollar industry.

Chuck Barris grew up in Philadelphia, where he was born in 1929 ... or 1930 ... or 1932. Although he's written two autobiographies, he hasn't gone into much detail about his childhood. Not that what he writes can be trusted anyway: He filled his first, "Confessions of a Dangerous Mind: An Unauthorized Autobiography," in 1984, with tales of his adventures as a CIA assassin. In his second memoir, "The Game Show King: A Confession," in 1993, he made nary a mention of his CIA fantasy, or even of the first book. Some of the stories in the first book are repeated in the second, but with differing details. He once wrote a lovely essay for Sports Illustrated in which he described promising to marry his future wife if Jim Plunkett of the Oakland Raiders completed a touchdown pass in the football game they were listening to on the radio in Los Angeles. In "The Game Show King," the promise comes in a New York hospital as his would-be bride lies in agony with peritonitis. Though most sources cite his birth date as June 3, 1929, he wrote about his 50th birthday occurring in 1980 in "Confessions of a Dangerous Mind," and once wrote another Sports Illustrated piece in which he recalled being an 18-year-old vendor in Shibe Park in 1950.

Here's the story according to Barris: He's the son of "a less than inspiring dentist." The family, which included a sister seven years younger than Chuck, was left with nothing when his father died of a stroke. Barris, who graduated from Drexel Institute of Technology in 1953, bounced around for a few years in various jobs, including TelePrompTer salesman (he says he never sold one), book salesman (never sold one) and fight promoter. He eventually moved to New York, married the former Lyn Levy, got a job as a page at NBC, conned his way into a prestigious management training program by forging letters of recommendation from members of the board of NBC's parent company, RCA -- NBC executives never checked -- then joined the daytime sales department and promptly got laid off in an efficiency cutback. (In typically untrustworthy Barris fashion, the parent company in his telling of this story is General Electric, which hadn't owned NBC since 1932, and wouldn't again until 1986.)

He pounded the pavement for a year, unable to land a job until an ABC executive asked him if he wanted a temporary gig: Barris was to take the train to Philadelphia every day, sit on the set of "American Bandstand" and keep an eye on Dick Clark, who was caught up in the payola scandal. He had a stake in publishing companies, record labels and even pressing plants whose records he promoted heavily on "American Bandstand." ABC forced him to divest himself of his music business interests and, Barris says, assigned Barris as his watchdog for a few weeks until he could go to Washington and testify before a House subcommittee. Barris would at least get a new suit out of the deal, because ABC thought a watchdog should dress the part.

But Clark didn't go to Washington for more than a year. In the meantime he gave Barris a desk and chair and made him feel welcome. With nothing to do, Barris wrote a long memo every day detailing the minutiae of the show, along with some jokes and philosophical observations. Barris claims that the sheer heft of his 500-page document helped Clark come out of the hearings unscathed, earning Barris a lifetime friend in Clark and a full-time job in ABC's daytime television department.

It didn't take Barris long to get in trouble with the ABC suits. Though not a musician (his no-volume electric guitar playing on "The Gong Show" notwithstanding), he managed to write the song "Palisades Park" and get it to Freddie "Boom Boom" Cannon -- a good friend of Clark's: He appeared on "American Bandstand" more than any other artist, and recorded for Swan Records, formerly a Clark label. Cannon's 1962 record went to No. 3, and ABC, which didn't want another payola investigation, forbade him from writing more. Barris has claimed to have written subsequent hits pseudonymously, but Cannon told the Allentown (Pa.) Morning Call in 1999 that he called Barris after the song broke, looking for more hits. "It was a fluke. I guess the guy just had one great song in him."

After convincing the network to let him open an office in Los Angeles, Barris made a pilot for a game show called "People Poker." There were five people from each of three professions, plus a "wild card," and contestants had to correctly guess the professions to collect a poker hand. Three electricians and two mechanics, say, would beat a pair of each. On the pilot show, according to "Confessions of a Dangerous Mind," the talent booker used five brain surgeons, five cops and five hookers, all female. The cops and hookers started fighting. The show never sold.

Meanwhile, Barris was bridling at ABC's conservatism and bureaucracy. When he got in trouble again, for replacing his cumbersome title (director of daytime television programs, American Broadcasting Company, West Coast Division) with a sleeker one -- duke of daytime -- he decided he'd had enough, and struck out on his own. His mother had remarried a wealthy man. Barris borrowed $20,000 from his stepfather, developed "The Dating Game" and sold it to ABC, which paid for a pilot, but didn't put the show on its schedule, effectively killing it.

Barris was devastated, but good news was on the way. Two of ABC's new game shows were tanking, and the network needed replacements fast. "The Dating Game" was back in business. The show's format was simple: A pretty young bachelorette would interview three prospective bachelors she couldn't see. She'd choose one to spend a night on the town with. The game was sometimes played in reverse, with a bachelor and three bachelorettes. The whole thing was presided over by Jim Lange, a low-key disc jockey from San Francisco.

But as the shows began taping, Barris ran into an unforeseen problem: The contestants were getting down and dirty!

Bachelorette: Bachelor No. 3, make up a poem for me.

Bachelor No. 3: Dollar for dollar and ounce for ounce, I'll give you pleasure 'cause I'm big where it counts.Bachelorette: Bachelor No. 3, what's the funniest thing you were ever caught doing when you thought nobody was looking?

Bachelor No. 3: I was caught with a necktie around my dick.Bachelorette: Bachelor No. 1, I play the trombone. If I blew you, what would you sound like?

Bachelorette: Bachelor No. 2, what does a rabbi do on his day off?

Bachelor No. 2: A rabbit?

Bachelorette: No, a rabbi.

Bachelor No. 2: How the fuck do I know?

And so on.

Unable to use the shows with the blue talk, Barris hired an actor to come to the set and play an FBI agent. The actor warned the contestants that it's a federal offense to curse or even hint at anything lewd on the air. The contestants, none of whom were legal scholars, bought it. Barris was able to deliver shows that ABC could air, and "The Dating Game" became a hit.

"The Newlywed Game" followed in the summer of 1966. This time, four newly married couples were quizzed on how their partners would answer personal (and winkingly intimate) questions. The prize for the winners was usually some household appliance, which they'd invariably go bananas over as the other three couples looked crestfallen. Barris later revealed the secret behind these reactions: He'd ask prospective clients what their dream gift would be, then match couples who answered similarly on the same show. The host was Bob Eubanks, a somewhat toothier version of Lange. Unable to use the word "sex" on the air, "The Newlywed Game" substituted "whoopee," as in "whoopee session." The word became a trademark of the show:

Eubanks: Where will your husband say your worst whoopee session usually takes place?

Wife: In the bathtub.

Eubanks: In the bathtub?

Wife: Yes, because the water always makes his peeny shrivel up.

Oh, the critics hated it all. Television has hit an all-time low, they wrote. Bad taste has taken hold of the airwaves. Barris is catering to the lowest common denominator. ("I don't even know what the lowest common denominator is," Barris would grumble to a newspaper reporter years later.) Lange was so upset by the vitriol that Barris says he had to talk him out of quitting "The Dating Game." He wrote in "The Game Show King" that he told Lange newspaper critics were originally movie and theater critics, and "free TV is beneath them."

"'In my opinion, a good game show review is the kiss of death,'" Barris recalls telling Lange. "'If for some strange reason the critic liked it, the public won't. A really bad review means the show will be on for years.'" And, at least in the case of his first two shows, he was right. In one form or another, "The Dating Game" and "The Newlywed Game" stayed on the air for decades.

In September 1966, ABC called again. It had a flaming stinker on its hands in "The Tammy Grimes Show." The sitcom was the first casualty of the new season, dead after four weeks. Could Barris turn "The Dating Game" into a prime-time show to replace it? At the time game shows were a daytime affair. ABC's programming chief suggested a more glamorous prize for the winner to spruce up the show. So rather than a night at one of Hollywood's finest restaurants, the nighttime winners would get a romantic vacation, chaperoned by a staffer from the production company. Barris would claim in "Confessions of a Dangerous Mind" that these trips abroad served as cover for him on his CIA assignments. (Whenever Barris relates this story, however the details change, one thing stays constant: He said he could have "The Dating Game" on the air in six weeks, hung up the phone and threw up.)

"The Newlywed Game" went to prime time three months later, but with no upgrade in the prizes. Barris wouldn't allow it. A wife might playfully whack her husband over the head with her cardboard answer card for getting an easy one wrong with a toaster at stake, "but put a yacht up there and you've got an entirely new show," Barris said. "The fun will turn to violence. What you'll have is 'The Death Game.'"

With two hit shows, Barris was hot. "Produce a hit television show and the Network Biggies will listen very carefully to what you have to say," he wrote. "Produce two hit television shows, one after the other, and the NBs will take almost anything you have to offer, sight unseen."

And that's what happened. Barris sold three more shows: "The Family Game," a "Newlywed Game" variant with parents and kids replacing married couples as contestants; "Dream Girl of 1968," a yearlong beauty pageant that foreshadowed the far spoofier "$1.98 Beauty Show" a decade later; and "How's Your Mother-in-Law?" a game with a courtroom setting that put the proverbial family nightmare on the hot seat, thus violating -- unsuccessfully, as it turned out -- the TV rule that you can't attack Mom.

Counting the nighttime versions of "The Dating Game" and "The Newlywed Game," Chuck Barris Productions was putting 27 half-hours on network television every week. The freewheeling flower-power style that Barris had used to run the company in its early years -- company meetings kicked off with folk music jam sessions, and employees could wear whatever they wanted -- gave way to a more corporate operation. Barris went public in 1968 as Barris Industries.

Other shows followed: There was "The Game Game," which was kind of complicated -- a contestant and three celebrities trying to figure out what a panel of psychologists would say was the best solution to a problem -- and not successful, validating Barris' theory that the simpler the show, the greater the chance of success. There was also a one-hour Mama Cass special, and "Operation: Entertainment," a variety show inspired by Bob Hope's Christmas shows. It was taped at domestic military bases.

By 1974, Barris' shows had dropped off the network schedules, one by one, with "The Newlywed Game" ending its first run in December. So that year Barris wrote a bestselling novel. He may have been the King of Schlock, but his heroes were F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway and Tom Stoppard. Upon reading "Love Story" he decided he could write a better book, so he spent six months writing "You and Me, Babe," the fictionalized story of his since-ended marriage to Levy, which sold 750,000 copies thanks to heavy promotion. He dedicated it to his 12-year-old daughter, Della, who would soon make occasional appearances on her father's new show.

It was 1976 and Barris had yet another game in production. But the host, John Barbour, wasn't working out. He just didn't click with the show's concept. NBC gave Barris an ultimatum that no game show producer had ever heard before: You host the show, or no sale. And that's how "The Gong Show" got its lunatic of a host, and that's how Chuck Barris became a star.

"The Gong Show" was a spoof of TV's old amateur talent shows. A panel of three B-list celebrities (Jaye P. Morgan, Jamie Farr, Arte Johnson, Rex Reed, Pat Harrington, Phyllis Diller, Scatman Crothers, etc.) judged the acts as they sang, or did the hula, or (in the case of a pre-Pee-wee Herman Paul Reubens) impersonated a dripping faucet, or whatever. Barris booked the occasional decent act to make the bad acts look worse. After 45 seconds, the panelists could ring a huge gong to make the act stop. Any act that survived the full 90 seconds would get a score of 1 to 10 from each of the three judges, with 30 being the top score. The winner on each show would receive a prize of $516.32 and a gong-shaped trophy.

In the '60s, Barris would explain to his staff that a lot of people eat while they watch TV. "If you can make something happen on the program that will stop their forks halfway between their plates and their mouths at least once each half-hour, you'll have a hit television show," he'd say.

Anyone brave enough to eat while watching "The Gong Show" likely had a fork permanently suspended in midair.

And at the center of the madness was Barris. He squinted at the camera, sometimes from under a hat that he pulled down over his eyes. He clapped incessantly, sometimes stopping just short to fool the audience, which clapped along with him. "Back with more stuff," he'd say, "right after these messages." He strummed an electric guitar (unmiked, because he was a lousy player), danced, made fun of the acts. Whenever there was a dog act, he'd smear Alpo on his crotch beforehand, the better to create onstage embarrassment. For 10 years he'd been telling his hosts to keep it low-key. The repetition of a daily show seems boring to the cast and crew, he'd tell them, but not to the audience. They like you the way you are, steady and calm. Resist the temptation to jazz it up. "Then I go ahead and perform about as low key as a whirling dervish, busting every one of my rules," he wrote. "I just got crazier and crazier," he said years later.

The show created stars: The Unknown Comic, a comedian so awful he wore a brown paper bag over his head ("Is my fly open?" he'd ask Barris, who'd say no. "Well it should be. I'm peein'!"); Gene Gene the Dancing Machine, a chunky stagehand who danced frenetically; Father Ed, another stagehand who dressed as a priest and spewed pseudo-biblical advice. ("When a man asketh you for $5,000, giveth him $500. He wilst not bother you anymore and you wilst be $4,500 ahead.") A prime-time version followed, with a more glamorous first prize: $712.05.

But the biggest star was Barris himself. He liked getting the good tables and parking spaces and never having to stand in line for anything, but for the most part he had a hard time with the loss of privacy that comes with fame, with the loss of that barrier between himself and strangers. "On an airplane, traveling from New York to Los Angeles," he wrote, "a dignified businessman knelt down by my aisle seat and did his lizard imitation, licking my cheek with his tongue." He recalls a woman yelling to her husband at a crowded bookstore, "Look, Morris, the moron can read!" And a woman waiting at a red light asked him to roll down his window and said, "My girlfriend and I just want you to know we can't stand you." Barris, noting the endless congeniality of his friend Dick Clark, wrote, "I behaved exactly the opposite. I never fully understood why I acted the way I did."

The critics were no kinder than the man and woman on the street. Oh, they hated it all again. Merciless! Humiliating! Stupid! Lowest common denominator! Mike Wallace grilled him on "60 Minutes" about demeaning people. "The contestants on our shows come because they have a good time," Barris protested. "These people don't take participating on a game show as seriously as you think they do, Mike. It's not a big sociological thing. They just want to have some fun."

Newsweek dispatched its entertainment editor, Maureen Orth, to report on "The Gong Show" in 1977. Barris disarmed her by asking what talent she had. She said she could do her old high school pompom routine and he booked her on the show. By the end of her report, she's dancing the Charleston with a midget as the closing credits roll, having scored a second-place 26 with her "Gimme a G! ... O! ... N! ... G!" routine to "On Wisconsin!"

In 1978 Barris produced and hosted "The Chuck Barris Rah Rah Show," a "Gong Show"-inspired variety hour that featured an odd mix of old-timers (like Cab Calloway), '50s rock stars (like Chuck Berry), then-current variety show staples (like Jose Feliciano) and amateur acts. It lasted six weeks. That fall, "The $1.98 Beauty Show" sicced the "Gong Show" ethic on beauty pageants. The winner, after enduring abuse by confetti-tossing host Rip Taylor, would be awarded the titular check and a bouquet of rotting carrots. The critics weren't crazy about that one either, but Barris called it one of his favorites.

Also in 1978, the Popsicle Twins appeared on "The Gong Show." Barris used to keep the NBC censors off the show's back by throwing sacrifices at them -- acts he knew the censors wouldn't approve, but that would distract them from the acts he wanted on the air. The Popsicle Twins were one of the stooges, but the censors didn't get the dirty joke, so the Twins made it onto the show.

The act was officially called "Have You Got a Nickel?" Two barefoot teenage girls (who weren't twins) walked onstage, giggling abashedly, wearing shorts and T-shirts. Each of them sat down cross-legged and, to the tune of "I'm in the Mood for Love," proceeded to fellate an orange popsicle. Phyllis Diller gave them a 0. Jamie Farr gave them a 2. Jaye P. Morgan (who would later be fired for flashing her breasts on camera) said, "That's how I got my start," and gave them a 10. She was rewarded with one of their popsicles.

"I'm fairly certain that's when I first thought of chucking it all and moving to the south of France," Barris would later write.

By 1980, "The Gong Show" was losing steam. Several times Barris has told the story of saying, "There must be more to life than game shows" to the makeup woman during a break in "Gong Show" taping, and the woman whispering back, "There is." He decided to make "The Gong Show Movie," with his friend Robert Downey Sr. writing and directing. Midway through the production, Barris decided he wanted to direct it himself, which he did with Downey's blessing. Barris turned Downey's slapstick comedy into an attempt at seriousness, with disastrous results. The picture bombed.

"Life is cruel enough without Chuck Barris around," read the Albuquerque Tribune's review, and soon, he wouldn't be. For the next half-decade, he scaled down Barris Industries, wrote his first autobiography and contemplated that move to France. In 1986, with his girlfriend and future wife, Robin "Red" Altman, he went.

The Barrises lived in Saint-Tropez for several years, with Chuck occasionally returning briefly and unsuccessfully to the game show wars. They split up in 1999. He published his second autobiography in 1993 and made a cameo appearance in Downey's oddball movie "Hugo Pool" in 1997. And while he was splashing around the Mediterranean in his boat and trying to become an ace at boule, a form of lawn bowling, American culture caught up with him.

A wave of real people had begun showing up on TV, most notably on the show "Real People" (host: "Gong Show" washout John Barbour) in 1979. The wave never let up: "The People's Court," which debuted in 1981, brought back the old '50s format of the real-life courtroom drama, but where shows such as "They Stand Accused" had used ad-libbing actors, "The People's Court" used actual folks, who agreed to have their actual small-claims court cases adjudicated on the show. People magazine called the show "the 'Gong Show' of U.S. jurisprudence" and its retired judge, Joe Wapner, a serious version of Barris. The American Bar Association Review made the same comparison. The real people in court format is still going strong, with Judge Jerry Sheindlin in Wapner's old chair, and competition from his wife, "Judge Judy," as well as "Judge Joe Brown," "Judge Mills Lane" -- and even "Judge Wapner's Animal Court."

The daytime talk show format, once the province of celebrity chat and caring, sharing Phil Donahue, turned itself into a voyeuristic festival of real people and their real problems in the '80s, with Sally and Geraldo and, to a lesser extent, Oprah, and a full-fledged freak show in the '90s, with Jerry and Jenny and Maury and Rolanda and Ricki and Montel and does anybody remember "The Tempestt Bledsoe Show"? The producers of these programs would sometimes admit they had no idea why people came on and made such fools of themselves. Chuck Barris knew. As an exasperated Warren Beatty said about Madonna in her narcissistic 1991 documentary, "Madonna: Truth or Dare": "Why do anything if it's not on camera?"

The '90s brought "America's Funniest Home Videos" and MTV's "The Real World," both of which spawned endless imitations, all of them proving over and over that people will do anything to get on TV, and people will watch them. And then came the Internet, with its voyeur cams and bedroom cams, and the current wave of reality game shows that leave audiences agog at the things people will do to get on TV -- audiences that keep tuning in.

It's not just Barris' ethic that survives. His methods are all over the airwaves as well. The chaos and noise of "The Gong Show" live on in almost all youth-oriented TV. The show's talentless performers became the "Stupid Human Tricks" contestants on David Letterman -- the same David Letterman who used to be a panelist on "The Gong Show," where he no doubt learned the trick of using stagehands as entertainers. Barris' addled master of ceremonies character can be seen in Conan O'Brien, Tom Green and squinty-eyed Adam Carolla of "The Man Show."

The time may be ripe for a Barris revival, or at least an image upgrade, but it's going to have to wait a little. Charlie Kaufman, the hottest screenwriter in Hollywood after "Being John Malkovich," has adapted "Confessions of a Dangerous Mind," and Johnny Depp signed to play Barris early this year. George Clooney was reportedly on board to play Barris' CIA recruiter, but financing fell through in February because the deal couldn't get done in time to guarantee that filming would be completed before this summer's anticipated writers and directors strikes -- strikes that would mean even more reality shows flooding the TV schedule.

Where can reality TV go that it hasn't gone before? Barris has plenty of unused ideas. One that he used to talk about a lot was "How Low Will You Go?" or simply "Greed" (a title his pal Clark used for a "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire" clone). Contestants would try to underbid each other for such jobs as kicking an old man's crutches out from under him or shooting a little boy's dog. Reality shows have barely scratched the surface of Barris' tongue-in-cheek vision. "The ultimate game show," he has said, "would be one where the losing contestant was killed."

Which almost happened on a Barris show. In "The Game Show King," Barris relates the story of Ivy Flotsam, a contestant on a Barris revival of the '50s game "Treasure Hunt." In the show, host Geoff Edwards gave contestants a choice between cash, which he'd count into their palm, or the prize hidden in one of 25 boxes onstage, which ranged from huge cash bundles to worthless crap. Edwards was a master at milking the suspense to the point of sadism.

Ivy Flotsam didn't appear to be in the best of health even before Edwards began torturing her. "You have just won ... twenty ... five ... thousand ... coffee beans!" he said, building her up and deflating her. But there was also something to put them in: "A brand new ... automatic ... coffee grinder!" Up she went, and back down. By the time he told her that she'd also won "your very own ... picnic basket!" Flotsam wasn't falling for it anymore. Dejected, she accepted the beans, grinder and basket from Edwards and began to walk back to her seat, but Edwards stopped her one more time, looked into the box and told the exasperated Flotsam to hang on, he had something for her to put her heavy bundle in. "Why don't you try putting it down ... in the back of your ... 1960 classic Rolls-Royce!" At which point Ivy Flotsam fainted dead away, one eye open, staring.

The crew was sure she'd died. The cameramen whirled their cameras around the studios, searching for something to focus on and settling on the audience's shoes.

"Me?" wrote Barris, "I had a million questions. Was a death on the show good for the ratings, or bad?"

He wouldn't get his answer. Ivy Flotsam survived to tell her tale on "60 Minutes," where Mike Wallace asked her if her experience on "Treasure Hunt" was a happy one.

"Are you kidding, Mike?" she said. "I had the time of my life that night."

Shares