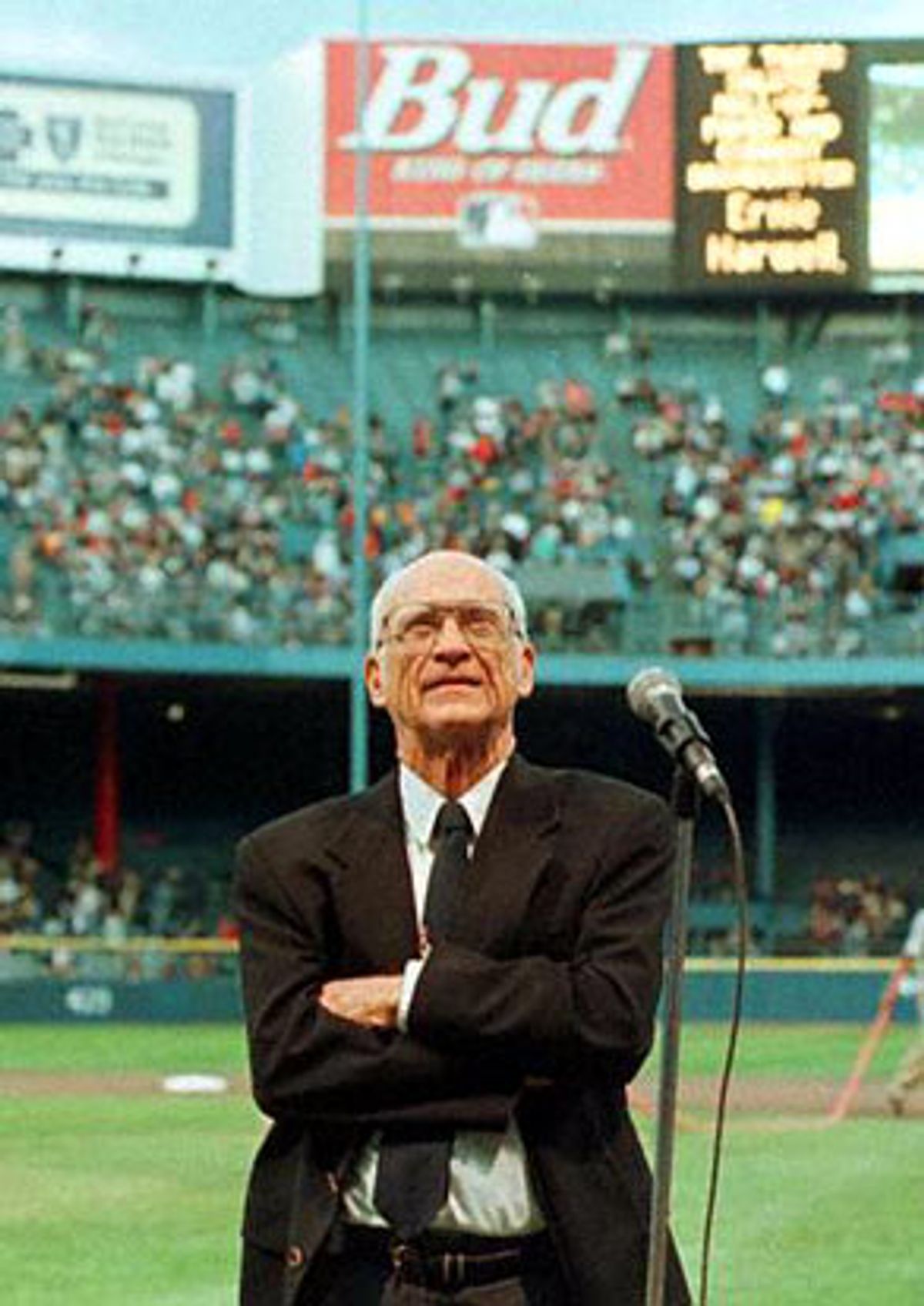

This is the last Michigan summer that will sound like a Michigan summer. Ernie Harwell is retiring.

It's possible that no one has ever broadcast more baseball games than the Detroit Tigers' 84-year-old announcer. He began calling his hometown Atlanta Crackers in 1946, moved up to the big leagues in 1948 with the Brooklyn Dodgers, and was already an established veteran when he came to Detroit 43 years ago. Since then Michiganders have taken him everywhere, to the beach and the backyard, the picnic in the park and that spot beneath the pillow where he can only be heard by a kid who's supposed to be asleep. You could probably fill a ballpark with people who hear Ernie Harwell's voice and think of their father.

He's an author and a songwriter, with four books of baseball recollections and dozens of published songs to his credit. He nearly caused a riot when he hired Jose Feliciano to sing the national anthem in his not-quite Kate Smith style at the World Series in 1968, a year in which the Tigers' pennant run had helped bring a riot-torn city together a little. There were nearly riots in 1991 when he was -- and this is as hard to believe now as it was then -- fired.

He's among the last of a fading breed, the old-time radio announcer who comes to personify a team. Vin Scully is still doing Los Angeles Dodgers games a half century after replacing Harwell in the Brooklyn booth -- "My claim to fame," Harwell says. Herb Carneal, once Harwell's junior partner in Baltimore, has been broadcasting the Minnesota Twins since 1962. There are others. Joe Nuxhall and Marty Brennaman in Cincinnati, Harry Kalas in Philadelphia. But most of the old radio men, the great voices like Harry Caray, Jack Buck and Bob Prince, and before them Red Barber and Mel Allen, are gone, long gone. There will be others who spend many years with a team, but with most games on television now, they won't have the same kind of intimate relationship with fans that the great radio voices did.

Harwell's voice has become as much a part of Detroit baseball as the Old English "D" on the Tigers' jerseys. And he's a joy to listen to. He gives the score often, he tells great stories, he rarely spouts meaningless stats the way some announcers do, and he never whines. He has his trademark sayings, but he never seems to be doing Ernie Harwell shtick. His mission, successfully completed 162 times a year, is to report what's in front of him. "The bones of it," he's fond of saying, "is ball one, strike one."

And now he's leaving, retiring after 55 years in major-league baseball. Hard as it will be for Tigers fans to say goodbye to Harwell after carrying his voice with them for more than four decades, rough as it is for them to see him off after another last-place finish by Detroit, even worse is the possibility that a baseball strike will deprive them of the chance.

The players have set a Thursday deadline for a strike that would wipe out Harwell's swan song, cancel Ernie Harwell Day at Comerica Park, deprive his listeners of that final sign-off.

"I wouldn't worry about it because I've got no control over it," he says in typically sunny fashion. "People are going to forget me anyway, so it doesn't make much difference."

People are not going to forget him. If Ty Cobb was the greatest Tiger of all time, Al Kaline, a Hall of Fame outfielder who played from 1953 to 1974, is the most beloved. But Kaline defers to Harwell. "If I have a statue at the ballpark," he's said, "Ernie should have two."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Welcome to summertime in Michigan: "Hi, everybody, baseball greetings from Comerica Park in downtown Detroit, the Tigers against the Kansas City Royals."

Harwell's announcement in March that he would retire after this season came as a surprise. He's healthy and fit. His voice is still strong, his descriptions are sharp, and he loves his job.

"Ernie's personality to me is like a 20-year-old kid," says Jim Price, a former backup catcher for the Tigers and now Harwell's broadcast partner. "I'll come to the ballpark in a bad mood some day because I had a long day. I get here, I see Ernie, he's always in a good mood."

Ask Harwell why he's quitting and he'll recite an old radio joke: "'I heard your last show, and it should have been.' I didn't want somebody saying that."

He started in old radio, as the sports director at WSB in Atlanta in 1940. It was in that capacity that he once knocked unannounced on the door of Cobb, the cantankerous Georgia legend, and asked for an interview. The old outfielder invited him in, and not only did Harwell become friendly with Cobb, which was no mean feat, but he also used a story Cobb told him to sell his first magazine piece, to the Saturday Evening Post.

After serving in the Marines in World War II, mostly as a correspondent for Leatherneck magazine, Harwell began announcing for the Crackers, a minor-league team for which he'd been a batboy, in 1946. He was hired by the Dodgers in 1948, in the process becoming the only announcer ever to be traded for a player, moved over to the New York Giants in 1950, then became the first announcer for the Baltimore Orioles in 1954. He was behind the microphone for Jackie Robinson's second season and Willie Mays' first. He came to Detroit in 1960 and became part of the landscape. The giant picture over the main gate at Comerica Park is not of Tigers greats Cobb, Hank Greenberg or Kaline. It's a photo of Ernie Harwell.

"He's one of the voices of Detroit," says Elmore Leonard, a pretty good Detroit wordsmith himself and an occasional guest of Harwell's at the ballpark. "He's a fixture. I hate to see him go."

Ernie Harwell still sounds like old radio. He projects his voice, rather than caressing the microphone with it, the way younger announcers do. His style is conversational, sure, but he's not just talking. He's broadcasting. Speak with him off the air and that great, resonant, distinctive voice is a little deeper, a little quieter, a little more Dixie. People talk about his Southern lilt, and you can hear it on the air if you're listening for it, but more noticeable is the precise, clipped diction of a 1940s radio man who has to make himself understood through the static and noise of a distant Philco.

At this year's All-Star Game he was invited into the Fox Television booth with Joe Buck and Tim McCarver. As soon as he opened his mouth, Buck, whose father, the late Jack Buck, broadcast St. Louis Cardinals games for 48 years, said, "Listen to that voice, man. That's baseball." Invited to do a little play-by-play, Harwell demurred for a moment, then clicked right in: "This is Mr. Winn at the bat now with two out ..."

Twice he's had longer consecutive-game streaks than Cal Ripken Jr., baseball's all-time iron man. Aside from the year he was away after having been fired, he's missed exactly two contests: one when he attended his brother Davis' funeral in 1968, the other when he was inducted into the National Sportscasters and Sportswriters Association Hall of Fame in 1989. (He's in pretty much every Hall of Fame he could possibly be considered for, including the one in Cooperstown.)

And now he's going out on his own terms. It would have been great if the Tigers had sent him off with an exciting season, but on this July evening they are 36-62, on a six-game losing streak and in last place in the American League Central Division, 23 games out of first, seven and a half games behind the fourth-place Royals, tonight's opponent.

"He and I kidded off the air one time," says Price. "'Boy, good thing they didn't dedicate this year to you, Ernie.' 'Yeah, thank goodness.' I think it's very sad. I was hoping it would be a real solid year for him."

No such luck. The Royals, winners of 10 of their last 11, have arrived in town to find the Tigers not just losing but in turmoil. General manager Dave Dombrowski has said some ugly things about the effort-to-salary ratio of several players to a group of season-ticket holders, then denied saying them, then been busted by the emergence of a cassette recording of his comments.

The controversy has replaced the losing as topic A in Detroit sports circles.

"I think Shakespeare wrote a play about this stuff," Harwell says. "'Much Ado About Nothin'.' They've really blown it out of proportion."

He says the losing doesn't bother him much either. "We've had that going now for 10 years, so I'm sort of immune to it, I guess. It'd be a lot more fun if you had a team in the pennant race. That's the ideal situation. I think most people think you're a good announcer when you have a good team and you're a bad announcer when you don't have a good team. But I've had good and bad. I'm used to it. I just take it as it comes. The game's the thing anyway. I'm just there to report it."

As the game's first batter approaches the plate, Harwell sits perched on the edge of his chair in the press box, leaning on his forearms, which rest on a scorecard and an ancient leather index card file containing handwritten cards on each team's players, arranged according to the batting orders. Harwell updates each player's card in the offseason with his basic stats. He uses them so he doesn't have to page through media guides. "I don't use it much, but it's there if I need it." He wears his headset microphone over a golf cap, having put aside the berets and Greek fisherman caps he favored for a while. Price sits to his left, and Dan Dickerson, who does play-by-play of the middle three innings, to Price's left. The field-level seats below them are mostly empty.

"Well, here they are," Harwell says on the air, "the Kansas City Royals. Sort of reminds you of a hot dog. They're on a roll. Chuck Knoblauch will lead it off."

He can be corny and old-fashioned. A team that's putting a lot of men on base has "more runners than a sled factory." An umpire might be an "arbitrator" or "the ol' maitre d' from Tennessee." Teams are sometimes referred to in early 20th century newspaper style: the Bostons, the Clevelands, the Detroiters. Players, managers and umpires often get a formal treatment: Mr. Pujols, Mr. Fick, Mr. Higginson. Hitters are, like the Mighty Casey, "at the bat."

And then there are the "Ernieisms," phrases and sayings Harwell's made famous. A collage of them serves as the opening theme to Tigers radio broadcasts. After a called third strike: "He stood there like the house by the side of the road," or "He's called out for excessive window shopping -- he looked at one too many." A home run is a shouted, elongated "Loooong gone!" A double play is "two for the price of one." And when a foul ball reaches the seats: "A man from Plymouth will take that one home," the city pulled off the top of his head each time.

Though his trademarks sound like they come from the golden age of wireless, they're actually of relatively recent vintage, mostly since the '70s. And for all his old-timey charm, Harwell is a fan of right now. "I'm not one of these good ol' days guys," he says. "I like the past all right, but it's past. We're living in the present." He loved all the history represented by Tiger Stadium, the 88-year home the team left after the 1999 season, but he also loves the new Comerica Park, with all its modern amenities. And just this month, Harwell mentioned in his weekly Detroit Free Press column that he thinks the greatest World Series of all time was ... last year's.

"The great thing with Ernie, I think, is that he always stayed current," says Jon Miller, ESPN's lead baseball announcer and the voice of the San Francisco Giants. "Ernie's not one of those guys who as he got older started getting bitter and saying, 'Well, these guys today, they can't play compared to the old guys.' Ernie has always said, 'Really, I think the guys today are the best they've ever been,' athletically and whatnot. And I think that's part of why he's been able to last so long, because he stays fresh."

Not that the past is his enemy. The Royals' Luis Alicea is on first base with one out in the first inning: "Man on first, here's the pitch, it's a ball, low. Ninety-five stolen bases for this Kansas City team, they lead the league. In 1957 the Washington Senators stole three bases. No, they stole 13 bases, the whole year."

Harwell is a storehouse of baseball trivia, history and knowledge. "Some of it's off my head," he says. "I have my cards too that I bring out with me, index cards. I'll grab a bunch of them when I leave home, and if it works in I work it in and if it doesn't I don't use it."

After pulling that stolen-base stat out of the hat, he talks about the Senators' leading stealer that year, with three, "our old friend Julio Becquer," pronounced Becker. "He later became Beck-AIR, after he got in the big leagues a while."

Before tonight's broadcast is over he'll tell several more stories, all of which are pertinent to the action at hand and all of which draw laughs from and light-hearted interplay with Price. "He's a treasure trove of stories about the game," Miller says, fondly recalling a long train ride he once took with Harwell, on which he heard a bunch of them. "When he first came up Leo Durocher was there. He once had a fight with Leo on a train! Leo was buggin' him and Ernie decided he wasn't going to take it and they ended up scufflin'. He was there for the Bobby Thomson home run, Willie Mays breaking in to the big leagues."

Most of tonight's stories are a bit more down-to-earth, like this one about Ernie Fazio: "Well, we're talking about bats and weights and so forth. Ernie Fazio, the light-hitting Houston infielder, switched from a 33-ounce to a 29-ounce, and he said, 'After I strike out, a 29-ounce bat is a lot easier to carry back to the dugout.'" Fazio played in the early '60s.

Harwell sometimes refers to himself as a historian of baseball -- usually by way of saying that his historian's perspective allows him to realize that he, like everyone, can be replaced. "Heck, when I was 8 or 10 years old, I was reading the [Baseball] Guides from 1905, 1906, 1908, about the World Series. I read that stuff just like it was fiction. So I always sort of absorbed all that stuff," he says.

He also calls himself a failed sportswriter. By the age of 16 he was confident enough of his baseball knowledge that he wrote to the Sporting News offering to be the paper's Atlanta correspondent, a job he'd noticed was unfilled. He signed the letter W. Earnest Harwell to sound older. (His first name is William.) He got the job. He also worked the copy desk at the Atlanta Constitution while attending Emory University, a job he credits for his way with words. "That's the best training I ever got as a writer," he says, "looking at other people's stories, seeing what worked and what didn't." But newspaper jobs were scarce in 1940, when he graduated, so he auditioned at WSB. "I got lucky and won it," he says.

He got the Crackers job during the war, after he filled in for a few games while in uniform, before the Marines ordered him to stop. He took over after his discharge, in 1946.

Harwell made the bigs because Branch Rickey, the legendary Dodgers general manager, had scouted him -- "He was very, very far-reaching, you know, he covered everything" -- in anticipation of Red Barber's leaving to broadcast the 1948 Olympics. That didn't happen, but Barber did fall ill.

"Branch Rickey called and said, you know, 'Red, we don't know whether he's gonna live or die. He's sick. I'd like to have Ernie Harwell come up and replace Red Barber,'" Harwell recalls. "My boss, Earl Mann, who owned the ball club, said, 'Well, he's under contract. If you really want him, Mr. Rickey, send me your catcher from Montreal, Cliff Dapper.' So I'm in the big leagues, traded for a minor-league catcher."

And there you have it. The only broadcaster ever traded for a player. "Anything that gets you to the big leagues," Harwell says. "It was a little unusual. It got me a little publicity from time to time. It's one of those things people like to bring up."

It even worked out for Dapper. "He got to manage the Crackers, and he loved Atlanta. He told Buzzie Bavasi that and Buzzie told me that. Atlanta was a good franchise. They were owned by Coca-Cola. High-class operation, independent. He liked it."

In Brooklyn Harwell came under the tutelage of Barber, who managed to pull through and live for another 44 years. Baseball's first great broadcaster was the closest thing to a mentor Harwell would ever have.

"Red was sort of a tough taskmaster, and I think that was good for me." Harwell says. He says that before working with Barber he thinks he already had most of his basic approach -- give the score often, act as a reporter rather than a cheerleader -- "but it was emphasized by the way he did it."

The Giants had come calling after his first year in Brooklyn, but Harwell turned them down because he didn't want to leave the Dodgers so quickly. A year later, in 1950, "they made me an offer I couldn't refuse." He moved across town to the Giants booth, where a year later he would witness the most storied pennant race in baseball history, the "Miracle at Coogan's Bluff," the Giants' comeback from far behind to tie the Dodgers, then beat them in a playoff.

Harwell's new partner was Russ Hodges, a far more pedestrian announcer than Barber or the Yankees' man, Mel Allen, but a fellow who holds a high place in baseball lore because of his radio call of Thomson's "Shot Heard Round the World," the playoff-winning home run against the Dodgers in '51: "The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant!"

Harwell was there that day too, on the TV side. It was the first sports series broadcast coast-to-coast on television, and he figured he had the plum assignment. Now, he jokes, only he and Mrs. Harwell know what he said that day.

"I just said, 'It's gone,'" he says. And immediately started worrying. "I had a little quick misgiving. You always have that sometimes. 'Oh boy, suppose Pafko, the left fielder, backs up against the wall.' I guess in my subconscious I was saying, 'Suppose he catches it.'"

Obviously, he didn't.

"A guy from the Sporting News gave me a picture, and doggone it the guy in the front row was catching the ball! I didn't realize it was that close."

Harwell calls it his most thrilling moment in baseball. "It was early in my career, for one thing. It was in New York, the center of media attention. It was the climax of a great comeback by the Giants, and the Giants and the Dodgers of course were hated rivals. It all came together in that one swing of the bat."

In 1954 the St. Louis Browns moved to Baltimore and became the Orioles, and Harwell was hired as their first announcer. Though this part of his career is almost never talked about, he was in Baltimore for six years, and he enjoyed himself, even though Baltimore was a football town and the Orioles were lousy. "We had some good times there. I loved Baltimore. Lulu" -- that's Mrs. Harwell -- "had a house there. She'll bend your ear off about the house she left in Baltimore to come here."

In 1960 the Tigers hired Harwell on the recommendation of their other announcer, George Kell, a Hall of Fame third baseman who finished his career with the Orioles and had spent a little time with Harwell in the Baltimore booth.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

"Now the pitch is on the way, he swings and misses, and the first half of the first inning is history. No score, the Tiges coming to bat."

Harwell, and almost nobody else, calls them the Tiges, just the first syllable. After 42 years of marriage, you develop pet names.

That marriage is ending happily. Once, of course, it ended unhappily. After the 1990 season, the Tigers and their radio station at the time, WJR (it's still unclear where the idea originated, and nobody's taking credit for it now), asked Harwell to announce that he would be retiring after one more year, along with his longtime partner, Paul Carey, who had already decided to call it quits at the end of the season. The team, Harwell was told, wanted to "go in a new direction."

Problem was that unlike Carey, Harwell, just shy of his 73rd birthday, wasn't ready to retire. He called a press conference and announced that he would be leaving after the '91 season, but he wasn't retiring -- he was being fired.

"It was a traumatic experience," he says. "You know, nobody likes to be told he can't do the job. But I don't think I got as excited as other people did. I looked at it as a business proposition. A guy hires you, he's got a right to fire you."

The fans didn't see it that way. The fans hit the fan. Bo Schembechler, the former University of Michigan football coach who was now the president of the Tigers, was widely perceived as the man behind the decision to fire Harwell. Once a revered figure in the state, he now got hate mail by the truckful and was eviscerated in the press. Fans besieged the team and the station with phone calls and boycotted Domino's Pizza, the chain owned by Tigers owner Tom Monaghan.

"I was flabbergasted by the reaction that it caused," Harwell says. "I thought there'd be a little ripple, maybe somebody'd call the ballpark, say, 'Who was that guy who used to do the game?' and stuff like that. Well, maybe a little more than that."

Harwell won't quite admit that the uproar was caused by a deep and abiding love for him among Tigers fans.

"I think there were a lot of angles," he says. "The announcer is here for years and people get used to him, number one. It's sort of a tribute to radio and baseball more so than the guy. And then I think, too, I was, if you'll pardon the expression, a poster boy for old age. You know, I was discriminated against because of my age and sort of the American throwaway-trash society. 'He's through. Let's dump this guy.' I had a lot of people at General Motors and Ford telling me, 'That happened to me. I don't like it either, but you hang in there,' and so forth. I think they identified with me because of that too."

Harwell played out his lame-duck year, then spent 1992 freelancing for CBS Radio and the California Angels. The Tigers, meanwhile, were bought by yet another pizza man, Mike Ilitch of Little Caesar's, who promptly hired Harwell back.

Harwell says the whole incident is forgotten, but he's never patched it up with Schembechler. "I tried to with Bo but he always resisted, so I finally gave up," he says. "I don't hold a grudge at all. My feeling was that it was a business deal. Everybody's forgiven, it happened, it's over."

After one year in the radio booth, Harwell switched to television in 1994, then returned to radio, his first love, in 1999. "When I was on TV, you know, I was on TV four or five years here without doing radio, and people would come up to me and say, 'What are you doing these days? Sorry you're not working anymore,'" he says. "Radio's got a great advantage because people can take it everywhere."

"He comes from an era that we're losing," says Mike Shannon, a former St. Louis Cardinals player who's been broadcasting Cards game for 31 years, mostly alongside Jack Buck, who died this summer. "We're losing the era of all the great television men that we've known through the past -- I'm talking about the Vin Scullys, and the list goes on and on -- they all started in radio. And until you do baseball on radio, I don't think you can fully understand it."

Television has replaced radio as the main way fans keep up with the home team. Instead of a handful of televised games a year, there are hundreds. And announcers aren't as important on television.

"It's a director's medium," Harwell says. "The director decides what's going to happen. On the radio, you know, we always say nothing happens until we say it does."

Also, where there were once 16 teams with two or three announcers each, now there are 30 teams with maybe a half dozen announcers each, not to mention the national television crews.

"It used to be when we started, we were the only game in town, and if you wanted to hear a game you tuned in on Harry Caray or Jack Buck or whoever," Harwell says, though matter-of-factly, not complaining. "Now you've got ESPN and Fox throwing games all over. You see them all the time. You're bombarded with all kinds of announcers, and I think it's just harder now for a guy to make an impact. It's sheer numbers if nothing else."

That Harwell has made an impact is clear from the constant stream of interviewers and autograph seekers he greets each day, from the piles of mail that the Tigers public relations department filters, lest he wear himself out fulfilling every request for a meeting, a favor, a personal phone call. As he walks around the ballpark, which he does a lot, people shout his name, ask him for autographs, want to shake his hand. He accommodates them all, and seems to believe this: "It's not me. It's the position more than it is me."

"I think that's true humbleness," says his wife, Lulu. "He doesn't know why people feel that way."

Dickerson, who shares play-by-play duties, marvels at the fact that Harwell never seems to get tired of the fuss people make over him.

"That's the amazing thing. You'd think at some point you'd see him go, 'I'll get ya later,'" Dickerson says, laughing at the very thought of a Harwell brush-off. "Never. We were in Florida, you know, there's about 200 people in the stands before the game, there's nobody there. And somebody goes, 'Ernie!' Yelling up from the stands. 'Can you sign my book?' And he goes, 'I'll be right down!' He left the booth! He went down, met the guy on the concourse. I've never seen him lose patience or get tired of it or even in a private moment say, 'For God sakes, is it ever gonna ...?' Not once."

"I like the attention," Harwell says. "I'm like anybody else. I like the people to make over me a little bit. It's nice. But I know deep down, it's not the most important thing. The most important thing is my relationship with God. That's got to come first."

Harwell became a born-again Christian in 1961, at a Billy Graham Crusade in Florida during spring training.

"I'm just a believer, you know. I'm a sinner like everybody else, but I just try to do the best I can. He takes care of me, that's the main thing. I don't worry about anything."

Price says that Harwell, who has been active in an organization called Baseball Chapel, doesn't proselytize, but did help him spiritually after Price's son Jackson, 7, was diagnosed as autistic. "We were bitter, you know: Why's this happening, why did this happen to me? Why did this happen to us? And I had watched Ernie for a long time, how he handled things. You know, when he was fired by whoever fired him, the Tigers or WJR, I know that was devastating, but he told me he forgave those people. I watched how he operated, how he handled himself as a Christian. And I wanted to know more answers, why we would be given this delightful little boy and he was autistic. He never really said anything to me. We just started talking, and I just grew with him and then grew on my own."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

"Here's a little bump past the mound toward second base, Febles grabs it and, ah ... "

Harwell hesitates as Royals second baseman Carlos Febles fields a slow roller and throws to first to get Tigers leadoff hitter Ramon Santiago on a close play. Price softly says, "Just got him" at the same time that Harwell says, "Can't make the play."

Price says again, "Just got him, Ern," and Harwell says, "Yup." Price recaps the play and Harwell says, "So there's one up and one down" without missing a beat. His error isn't mentioned again.

Even the great ones make mistakes. Is Harwell, at 84, losing it?

"My eyesight's great, as good as it's ever been," he says later. "That could have happened to me 25 years ago. Red Barber told me one time, he said, 'One time I got the wrong third baseman for Cincinnati. I'm doing Cincinnati games, I had the wrong third baseman in for the whole game. You know, he came to bat four times.' And I said, 'Well, if that happens to you, I'm not going to worry about what happens to me.'" Most people don't even notice the occasional mistakes, he says, so he doesn't dwell on them or apologize for them.

"He's as good as always," Price says, blaming Harwell's error on the difficulties of seeing in the twilight at Comerica Park. "All of us have problems sometimes with the glare. It's a hard glare." Dickerson agrees that Harwell sounds "exactly the same" as when Dickerson first heard him, as a little boy rooting for the 1968 championship team.

Harwell's certainly in good shape. He jumps rope and stretches every day, and sometimes jumps on a trampoline. He skips elevators too, instead walking the ballpark. "That gives you a little exercise you don't even know you're getting," he says. It also gives fans a chance to say hello or ask for an autograph.

"I followed him around yesterday," says Bill Eisner, a photographer for the team who's young enough to be Harwell's son, "and I was dying."

So why retire? A lot of baseball people are pushed out the door by travel fatigue, but Harwell loves the road. "When I started I knew I had to do it, so I figured I might as well do it cheerfully. The way I try to look at is, they're paying me to live in a nice hotel, eat good meals, and see my friends every day and go to ballgames," he says. "I love to read, and that occupies your time a lot. I don't mind it at all."

It's hard to nail Harwell down on a reason for his retirement other than his old radio joke and vague statements like "I didn't want to stay too long."

"He and I had always talked and he felt he could go another four or five years," says Price, who says he was "shattered" when Harwell told him of his retirement plans. Price says Harwell has never discussed his thinking with him. "Maybe it's just time," he says. "He's as good as always."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

"Well, here we go, second inning, no score in this muscular soap opera from Comerica Park this evening."

In the bottom of the second inning Harwell gives the score -- nothing-nothing -- at 7:28, 7:29 and 7:30. He gives the score at 7:33 and 7:35 when the Tigers score single runs. He gives it again at 7:36, and then when the inning ends at 7:40.

Jon Miller, who announced for Baltimore in the American League before moving to San Francisco, says he used to use an egg-timer to remind himself to give the score, the way he'd read that Red Barber used to do. "Ernie saw that one day years ago, and he said, 'How long before that runs out?'" Miller says. "And I said, 'I don't know, I think two and a half minutes or three minutes.' He said, 'That's a good idea to keep giving the score. In fact I think you should give it probably once a minute.' And I thought, Once a minute? Wow. Wouldn't that seem like that's all you're ever doing is just giving the score? And Ernie says, 'Well, we all want to believe that everybody's listening to the whole broadcast and hanging on every word, but the reality is that that's not the case. Most people are tuning in and out at random at any time. And the first thing they want to know is, What's the score?'"

Miller says this simple thought might account for Harwell's popularity.

"On top of his talent, his great voice, the warmth that he projects, the genuine person that he is, which comes across on the air, that may be one of the great reasons why they loved him so much in Detroit, and even the listeners weren't aware of that. Because I think your first reaction when you turn on the radio and you're in the car: What's the score? And if the guy doesn't give you the score, you're angry. Hey! Gimme the score! What's the score, for god's sakes? Well then I realized, hey, no matter who's tuning in when, Ernie's giving them the score almost immediately.

"He also told me that he never told a story that he couldn't fit in between pitches or between batters. If it took longer to tell that story than that, it was too long for the broadcast. And again, I sort of disputed that notion, but then as I saw how popular he was in Detroit, I thought, Well, that has to be part of it too."

Miller says Harwell is always thinking, "What I need to do here is provide this service for the fans."

That generosity extends not just to fans but to other broadcasters as well, particularly young ones. "I'm not much on giving advice," Harwell says, "but if a guy comes up to me and wants to talk, that's fine. Love to. Kids send me tapes all the time from places like, you know, Ada, Oklahoma, or Des Moines, Iowa, or somewhere like that, and I'll listen to the tape and give them a little critique."

One of those kids, in the late '80s, was Dickerson, now a booth partner. Harwell invited the young broadcaster, at the time a mere acquaintance, out to his house. "We sat at his kitchen table and listened," Dickerson says, "and it wasn't some perfunctory 'That's pretty good.' He really listened. He'd say, 'Now, you just said a pitch was down low. You don't have to use the word down and the word low. Just say low.'" Dickerson still has his notes from the session.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

"We didn't get hit hard by the storm," Price is saying on the air about the overnight rain, "how about you?"

"We didn't get hit too hard. We lost our power for about 12 hours," Harwell says.

"You didn't have to replace any of Miss Lulu's rosebushes or anything?"

"Not yet."

"Miss Lulu" is the former Lulu Tankersley, Mrs. Harwell since 1941. To Tigers fans, she's more of an offstage character than a real person, akin to Charlie Brown's Little Red-Haired Girl. (Suggest this notion to Harwell and he says, "She's a character, all right.") The broadcast-booth version of Miss Lulu is forever fussing over her rosebushes and cracking the whip on poor hapless Ernie.

They met at a dance when he was at Emory University and she was a year behind him at Brenau College, a women's school down the road in Gainesville, Ga. She followed him from Atlanta to Marines postings in South Carolina, North Carolina -- where they lived in a house with no electricity -- and Washington, and to baseball jobs in New York, Baltimore and Detroit. "She's been a great support for me," he says. "Probably the best thing that ever happened to me was hooking up with her."

They had four kids together, two boys and twin girls, all successful professionals now, none of them broadcasters. "They all wanted to make an honest living," Harwell says. Three of the four live within a few minutes' drive of their parents in the Detroit suburbs.

And Miss Lulu is probably the only Michigander who's happy to see her husband calling it quits.

"Yeah, I like it," she says with a Southern accent far more pronounced than her husband's. "I've been alone for many, many years at night. When we lived in Grosse Pointe I always got kind of bored with people telling me what a wonderful summer they had up north, because I couldn't go unless I went by myself."

Harwell says he'll still be pretty busy even in retirement, writing, speaking, acting as a spokesman for Kroger supermarkets and Comerica Bank, and filming a series of "vignettes" for Fox Sports Detroit.

And he says he'll pick up a hobby he hasn't had a lot of time for lately: songwriting. He says he's had about 65 songs recorded by various artists, including B.J. Thomas and Merrilee Rush, of "Angel in the Morning" fame.

" I just got started as a hobby, and I got into it, met a lot of good people, and began to collaborate with real professionals," he says. He wrote a song with Mitch Ryder, a Detroit hero, and wrote a few with Academy Award-winning songwriter Sammy Fain, who co-wrote "Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing." "That was one of my big thrills in music," he says.

Another was being approached by the estate of Johnny Mercer to finish a song that his family wasn't pleased with.

"Johnny Mercer's my songwriting hero, and after he died they had a lyric they didn't like, and they asked me to rewrite it, and I wrote it," he says. "We never got a record on it but it was a nice little tune. It was an old-fashioned song about sitting on a porch and writing a letter, which nobody ever does anymore, so we made a sort of a tavern song out of it."

Now he's sitting at a table in the Comerica Park press box cafeteria, singing: "'Sing, sing, sing every song/ Dance, dance all the night long/ Life is a party and doesn't last long/ So dance every dance and sing every song.' You know, like a tavern."

"I'm going to get back to it, I think, but it's a lot harder now," he says. "I just can't do a hip-hop song."

Harwell's musical career got him into the hottest water he's ever been in as the Tigers' announcer. In 1968, one year after Detroit had been racked by race riots, the Tigers won the American League pennant, an event that helped create some common bonds but didn't keep the city from being very much on edge, divided along racial and generational lines. Detroit hosted games 3, 4 and 5 of the World Series against the Cardinals. General manager Jim Campbell charged Harwell with finding singers for the national anthem. "Because I was a songwriter he designated me as the appointed singer picker," he says.

Harwell picked nightclub singer Margaret Whiting, Marvin Gaye and Jose Feliciano, who wasn't particularly well known yet, but came recommended by a music-industry friend. The Tigers were worried that Gaye, the Motown star, would sing an unorthodox anthem, and asked Harwell to speak to him. But Gaye planned to, and did, sing it straight. Feliciano, though, gave the song the Feliciano treatment, and set off a firestorm.

Veterans groups protested, sportswriters complained. Miss Lulu, on her way home from Detroit to Florida, where the family lived at the time, saw the newspaper headlines and was sure Ernie was about to lose his job.

"It was a Vietnam time," Harwell says, "and the people were very anti-hippie, and they thought he had long hair -- it really wasn't that long compared to what we saw later -- and he had the instrument of the time, you know, the hippie movement, he had the guitar, and he had his dog out there. He had on dark glasses, which was another symbol of hippie-ism. So they immediately sort of made a connection."

The Tigers, he says, were pretty good about the whole thing. "I got a little slap on the wrist, but that was all."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

"Halter hits a fly ball to right. It'll be foul, back in the corner, in the seats, and a gentleman from Livonia, with a glove on, makes that catch."

Harwell takes the middle three innings off while Dickerson teams with Price. He usually stays in the booth to watch the game and listen to the broadcast, but if someone wants to talk to him, that's OK too. He's so generous with his time that a reporter in town for three days to research a story on him confesses on the third day that he's just about run out of questions to ask.

"I think throughout all the years a lot of people have experienced his kindness. He never refuses anybody or anything," says Lulu Harwell. "He's always very upbeat, and I think people recognize that. His mother and father were like that. They were wonderful people."

Harwell's father, Davis Gray Harwell, was left paralyzed in Ernie's teen years by brain surgery to remove a tumor. He says that while he doesn't really picture any particular listener when he's broadcasting a game, he used to use his father as an imaginary sounding board. "In the old days, when my dad was alive, he was an invalid," he says. "I sort of thought about him a lot. I couldn't say I actually talked to him, but probably in the back of my mind." Gray Harwell died in 1960, during Ernie's first spring training with the Tigers. His mother, Helen, died six days later.

Much has been made of the Southern upbringing of many great baseball announcers. Harwell says a lot of that has to do with the fact that Barber, from Columbus, Miss., was the first to do baseball in New York. The Giants, Dodgers and Yankees had an agreement not to broadcast games, which Dodgers executive Larry McPhail broke in 1939 by hiring Barber away from the Reds. "They broke the agreement, McPhail did, and the other guys had to follow," he says. "And I think that was pretty important for the Southern guys because nobody had ever heard big-league baseball in New York or the suburbs, and the first guy they heard was Red, and then Mel Allen. And they were both Southerners. So it wasn't anything strange for Russ Hodges, another Southerner, to come along. Or even Connie Desmond, who worked with us, was from Columbus, Ohio, which was pretty close to being Southern. These people were accepted, and that might have been a factor."

Harwell also credits the South's storytelling tradition. "We didn't have any entertainment in the Depression. You'd sit on the porch and you'd hear your mom and dad talk about Uncle Joe and Aunt Jane and Cousin So-and-So and what they were doing, tell stories about them, so it just sort of came natural, I guess."

But he's quick to point out that Vin Scully, among others, proves that being Southern is not required. "Vin's the best of all and he came from New Jersey."

By the seventh inning the Tigers have built a 9-1 lead, a rare laugher for the Detroiters. They add another run. Now George Lombard, a young outfielder picked up in June from Atlanta, is batting for Bobby Higginson.

"Lombard digs in to wait on the next one. Here it comes. He takes a slow curve, and he stood there like the house by the side of the road and watched it go by. Struck him out."

"The House by the Side of the Road" is a 19th century poem by Sam Foss that Harwell had to recite as a boy, part of his treatment for a speech impediment, one of the more ironic childhood problems in broadcast history.

"I was tongue-tied. I couldn't say an S or a ch," he says. "I'd say ficken, or I'd say fister instead of sister. And my family was rather poor, we didn't have much money, but they had enough to send me to what we'd call a speech therapist now. I think then we called them expression teachers or elocution teachers." That teacher, Mrs. Lackland, helped him overcome his condition, and he was able to recite the verses and speeches and engage in the debates that were required of Atlanta grade schoolers at the time. Harwell says that years later, after a piece about them appeared in Guideposts magazine, Mrs. Lackland wrote him a letter and sent him a program from an Atlanta school event. "They were still reciting the same old speeches. You know, Lincoln's Gettysburg Address."

After the seventh inning an image of Wade Boggs, the former Red Sox and Yankees batting champion, comes on the Comerica Park video screen looking not unlike a schoolboy at a recital. He's standing rather awkwardly in front of a bookshelf, talking.

"Ernie, there's a saying," he says. "Definitely you are the best there was, the best there is, and the best there ever will be. That's Ernie Harwell." With the broadcast in a commercial, Harwell watches the video and listens on his headset. This is a nightly event, a video tribute from a famous admirer. "Congratulations on your Hall of Fame career, and Ernie, you are a grand gentleman. From Wade Boggs to you, all the best and may God bless."

The Comerica Park crowd stands and cheers, looking toward the press box, where Harwell leans out the window and waves his cap to them. So that the home audience doesn't miss anything, Price reviews the tribute each night as the eighth inning starts, adding his own congratulations to his partner. The day is fast approaching when Price will have to wrap up the season's last broadcast with his own final tribute.

"I've thought about it," he says. "It'll be a goodbye to Ernie, representing the fans. I want to represent the fans the proper way. I won't write it. I ad lib most everything. I have an idea what I want to say. It'll be tough."

Dickerson says he's thought about it, too. "I don't know how to do it without immediately veering into the maudlin," he says.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

"Well, here we go, ninth inning. The Tigers with a commanding lead here at Comerica Park, 10-1 over Kansas City."

Harwell's radio listeners probably aren't aware that he practically broadcasts the last half inning with one foot out the door. As soon as the last out is recorded and announced, he bolts, headed for his car and home.

"Game's over, Ernie's like a freight train," says WXYT radio engineer Phil McAuley, sitting behind Harwell and manning the sound board. "He'll bowl you right over if you get in his way. One night he forgot and left his headset on. It pulled him right back."

Harwell calls the top of the ninth with his tote bag on his lap. His quick getaway is an effort to beat the traffic, he says, though he admits that these days the traffic isn't much to beat. Tonight's crowd is 14,470.

The Royals get a walk but are quickly down to their last out, and Raul Ibanez waits for the pitch from Tigers reliever Juan Acevedo.

"Here it comes," Harwell says. "He swings and hits a chopper toward Easley. He grabs it. Here's the flip back to Pena. The game is over" -- at this point Harwell has his hands on the earphones of his headset, ready to remove it, and his chair is swiveled a half turn to the left to facilitate a quick exit -- "and the Tigers win it. The final score, Detroit 10 and Kansas City 1." The station cuts to a commercial, Harwell's headset hits the desk and he's up a short flight of steps, past the engineer's table and out the door, bound for the parking lot.

His last season is in its last-place dog days now. Soon enough -- too soon if there's a strike -- he'll call the last out for the last time, and there won't be a forgotten headset or anything else pulling him back. He says he'll miss the people more than the job, and he's not overly sentimental about his career coming to an end: "To a degree, but I can get over it. I don't wallow in it. It's over, it's over, we've got to move on."

That might be easier for Harwell than for Tigers fans. Michelle Arquette, 32, of nearby Perrysburg, Ohio, sitting in the upper deck with some friends, says she grew up listening to his voice. "It's going to be hard not hearing him on the radio anymore," she says. "He's Tiger baseball, in my opinion. I think it'll be very hard to find someone to fill his shoes. It's just: His voice is Tiger baseball."

Labor trouble willing, the Tigers have a day planned for him on Sept. 15. His final broadcast will be Sept. 29 in Toronto. Dickerson says he's heard the Blue Jays have some kind of tribute in the works. And he says his partner will take it all in stride.

"He's funny," Dickerson says. "The various tributes, people wanting him to throw out the first pitch, so he does that a lot. And people ask him, Well, do you mind? He says, 'No, I don't mind, but why don't you just put my face on the scoreboard and wish me good luck.'"

"It's gonna make him feel pretty nostalgic, I think," Miss Lulu says about her husband walking away from a game he's covered for six decades. "But he'll keep up with writing his column and making speeches, and he might write another book. And I'm sure he'll be at spring training in Lakeland next year."

Shares