After years of semi-isolation as a remote getaway on the edge of the Mexican Riviera, the indigenous village of Yelapa is dropping in on the world. In the past three years, Yelapa has paved its pathways, electrified its houses, installed 200 phones, cleaned up its garbage, and redefined alliances with Mexico's two largest political parties. It remains protected by its geography, since it is accessible only by boat, and by its almost unique heritage as a community whose people have owned their land since before the Spanish arrived. Now more tightly connected to the world of communications and commerce, Yelapa is attempting to become a new kind of frontier town, one that sets its own rules for trade.

The map of the Bay of Banderas is dotted with the names of small villages that have been obliterated by tourist development. The canonical example is a few miles south of Puerto Vallarta, at Mismaloya, where high-rise hotels dominate the beaches and a tourist restaurant occupies the spot where Ava Gardner once tethered her iguana. Former beach residents have been forced into the hills. Across the bay at its northern tip, Punta Mita, a five-star hotel and a million-dollar housing community sit on the site of a former ejido (land collective), and the displaced ejido residents live in cement-block houses outside the gate. Although the methods may have been a little rough, most Mexicans here like the result: a tourist center, second only to Cancún in popularity, which has created thousands of jobs.

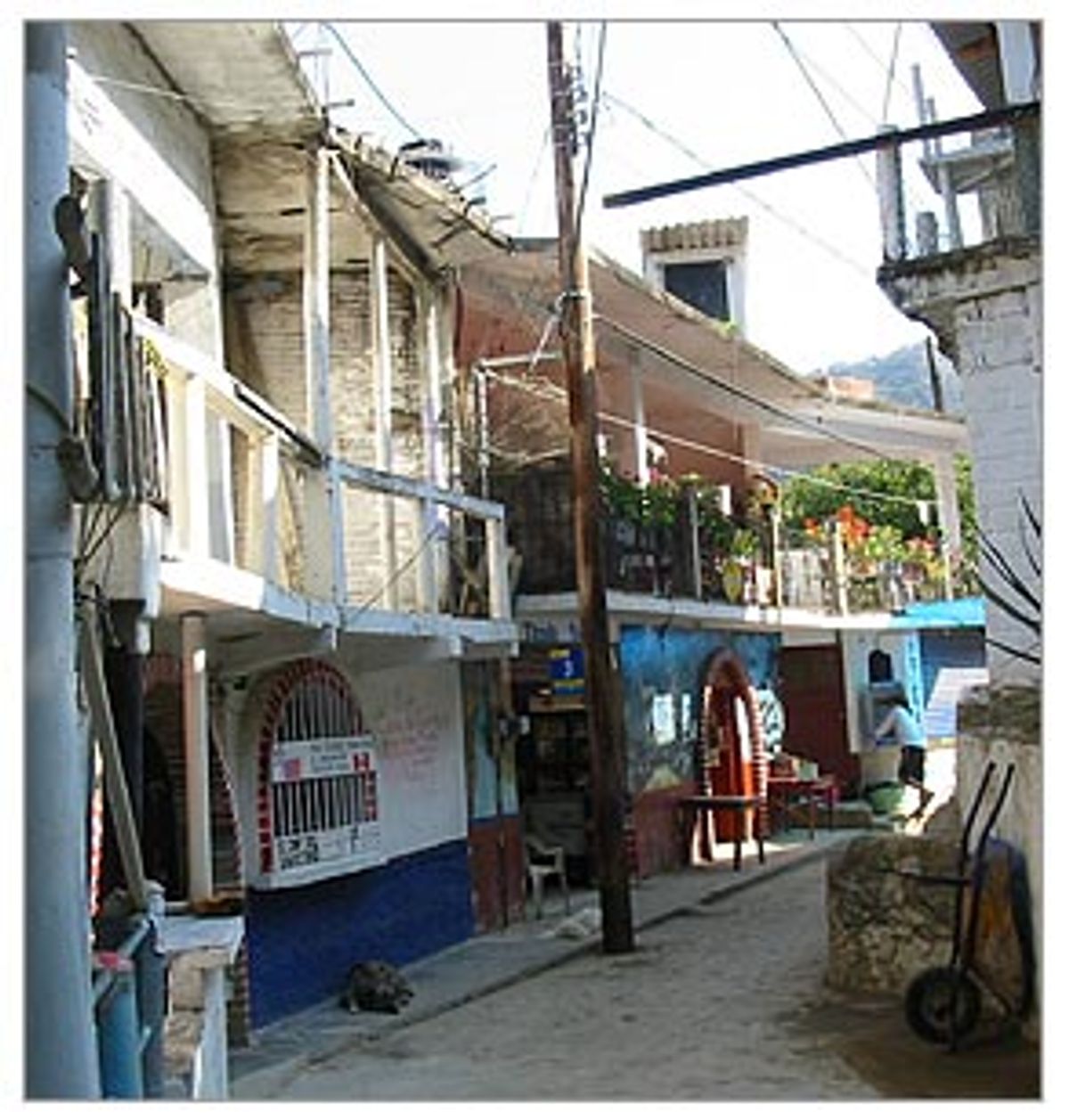

Yelapa shares in this popularity, and it has been a tourist mecca since the 1960s. However, visitors came here not for the traditional tourist fare of mariachis and margaritas but for the town's more primitive and simpler way of living. Except for a crude bulldozed dirt strip over the mountains to the south, there are no roads to or in Yelapa, hence no cars. Until three years ago, there was no grid-based electricity, hence no television, refrigeration or phones. There is still no common water supply, though a couple thousand people live here. Normally, meaning unless there has been a particularly egregious crime, there have been no police.

Yelapa has thus become known as a mellow place to live, where anything goes so long as it goes discreetly, as well as a spectacularly beautiful vacation spot. The land behind the town is mountainous jungle, which descends to a rugged coast of volcanic rocks interrupted by beaches at the mouths of the town's two rivers. The jungle is a deciduous rainforest that is home to more plant varieties than any other area on earth outside the Amazon, many of them in what looks like continuous flower. The climate, except in the rainy season, is perfect.

With property around the bay becoming ever more valuable, Yelapa would be a prime target for development except for its special status as an indigenous community with title to its own land. Like Pizota down the coast, Yelapa is part of the community of Chacala, which has group title to 50,000 acres on the bay. Unless the entire community votes approval, none of this land may be sold to outsiders. That, plus the continuing difficulty of access, gives Yelapa some elbow room in the global marketplace. Rather than sell its land, it has leased out valuable properties for income.

But it is no longer willing to take refuge in primitiveness. A long and bitter political struggle over control of Chacala's government seems to have ended in favor of the Verdes (Greens), a pro-growth group of young Turks affiliated with the business-oriented PAN (Mexican President Vicente Fox's party); and they are determined to modernize Yelapa by bringing its citizens some of civilization's amenities. Only this month, on March 7, the Verdes succeeded in blocking an attempt by the PRI-backed Rojos (Reds) to recall the Verde officers elected last June and hold a new election. The Verdes did it the old-fashioned way: by physically preventing a state-appointed mediator from attending the assembly where the vote was to be taken. They considered this only fair: The Rojos had forged the names of several Verde leaders as signatories on the election petition seeking their ouster!

"We are not going to let them win," says Alfonso Garcia Martinez of the Verdes. "The election was fair. We are going to stay in power by providing services for the people -- like the paving, like the town pier, like electricity." This in itself would be a remarkable change. Chacala has long been notorious for electing sticky-fingered leaders from both parties (a reputation that has helped keep developers away). The community is now in debt for back taxes that mysteriously disappeared on the way to the state treasury. It took Yelapa three tries to actually pay for the link to the electric grid, the first two payments having vanished.

At stake is the town's control of its tourist trade, the most important source of local revenue. Tourist guides fondly call Yelapa a fishing village, but it really isn't. The Bay of Banderas is getting fished out, and only a few people here make a living from the sea. Most money comes into town as remittances from relatives in the United States and from tourists. Almost every waterfront house is now occupied by or offered to tourists. And while it is the people of Yelapa who put up the money for electricity, because they wanted light, refrigeration and TV, tourists will certainly be attracted by the new and more comfortable ambience it provides (though with its steep hills, dusty paths and plentiful scorpions, Yelapa life will still be too gritty for some).

In response to the new technological possibilities, a community of more than a hundred expatriates, who have lived here quietly following their bliss for many years, has recently blossomed with entrepreneurial spirit. Of 33 rentals currently advertised on one Web site, 18 are offered by gringos, some of them trying to recoup their own rents and home maintenance expenses, and perhaps to make a living of their own; some entering joint ventures with locals, investing in houses and sharing the rentals with the landowners. This building activity pays local construction workers, and the visitors the houses attract pump money into the town. In addition the site lists a dozen retreats and yoga workshops hosted by outsiders.

The mere existence of yelapa.info, a free Web service run by longtime Yelapa visitor David Johnson out of Vancouver, B.C., indicates the biggest change in Yelapa: It is now globally accessible. When I came to stay here in 1989, you had to take the water taxi from Puerto Vallarta and set foot on Yelapa earth in order to rent a room. Now you can reserve a bungalow from Des Moines; you can also pay for it online, in which case the money may never even enter Mexico. The town-owned Lagunita Hotel now gets 40 percent of its reservations via the Internet.

The globalization has even become literal: Under a rock near the waterfall that is the town's main tourist attraction is a small package cached by a group of scavenger hunters who have posted its latitude and longitude online and invited its members to track it down with their GPS devices. So far three have found their way here and done so. Eco-bicyclists have discovered the bulldozed road and now skid down the mountainside and pedal incongruously through town in helmets and Spandex.

With global commerce has come its underside, crime and crack cocaine. Locally grown marijuana has always been available in Yelapa, and not a few of the northern visitors have brought their own pharmacopeia; but crack showed up only a few years ago and quickly caught on among a small part of the younger set. Late in 2002, a South African woman who has lived more than 30 years in Yelapa was brutally beaten and knifed by a group of youths who had been smoking crack and decided to steal her refrigerator. The physical attack was in retaliation for her having filed a complaint about the theft. It is a rueful comment on globalization that this group called itself the "Bin Ladens."

The tax problems and crack are seen by some here as threats to local autonomy. Although they have extraordinary rights as an indigenous community, Yelapans are also Mexican citizens and are part of a municipality based in the city of El Tuito, a few miles inland. It is from PAN governments in Tuito and Guadalajara (the capital of Jalisco) that funds have come for many of Yelapa's new civic improvements. Now fiscal sins and the mini-crime wave caused by half a dozen crack users have opened the door for Tuito to establish a bureaucratic beachhead in the town. Several police have been assigned to Yelapa, and for the first time in its history, it will have to observe an outside authority on its own turf. When you link with the world, the world links back.

Next: Paradise at $250 a square meter.

Shares