Brendan Hunt is nothing like the other Sandy Hook conspiracy theorists we’ve encountered. Yes, he thinks the December shooting was a kind of hoax to help the government seize power. But he’s not some right-wing “gun nut.” He’s not a militia member. And he’s not middle-aged and living in the middle of the country.

Hunt is in his 20s and lives in New York City, where he is an “actor, musician, artist and independent journalist.” He’s starred in Shakespeare plays and independent films and written books and news reports. His roots aren’t in the radical-right or libertarian movements, but on the left side of the political spectrum, where he’s aligned himself with Occupy Wall Street and says he’s produced segments for WBAI, a well-known public radio station in New York affiliated with the proudly “radical” left-wing Pacifica network.

Social scientists have used the term “fusion paranoia” to describe the merging of the radical left and right into a common concern about the government and centralized power to a point where they are almost indistinguishable on many issues. A British study released last year found that many conspiracy theories are pushed by core groups of people who are prone to believe in conspiracies of all kind — even contradictory ones.

And this isn’t Hunt’s first conspiracy rodeo. He has an e-book positing that Nirvana lead singer Kurt Cobain did not commit suicide, but was in fact murdered, and a movie about the Illuminati.

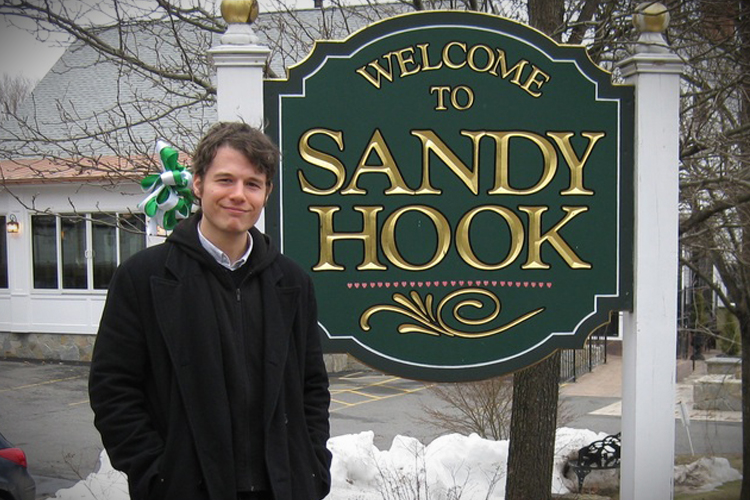

Hunt and a friend took a ride up to Newtown, Conn., to produce an “exposé” recently. In his videos, he identifies himself as a reporter with WBAI as he travels around speaking with residents, including Gene Rosen, the man who helped save six children and has been harassed by conspiracy theorists for it. (Several officials at WBAI did not immediately return requests for clarification on Hunt’s affiliation with the station.)

Wearing hoodies, Hunt and the friend come upon Sandy Hook Elementary from the woods in the back. They gingerly approach the fence line, taking time to point out the barbed wire and sign, noting that it’s under electronic surveillance. They point out key locations where they think one of the extra gunmen may have escaped through the woods while fleeing the scene.

“I believe that this event was pulled off by a group of tactical police officers of some kind, working as a unit, and that they didn’t complete their job in time, before the local police showed up and busted up whatever operation they had going,” he says in another video.

At the Masonic Lodge, which is — of course — involved in their theory, they find an ominous sign: A Masonic “G” written on the pavement. They try to peer inside the building through the windows. “I can barely make out a fridge and things like that,” one says.

Later they surreptitiously record a conversation with a bartender, whose real name they repeat. Hunt burps, complains about needing to make better “rendezvous points” with his buddy, and leaves huge portions of unedited video as he wanders around looking for his friend in the dark.

It’s not exactly the Zapruder film. The footage is innocuous and low-budget. One gets the impression that these are kids harmlessly goofing around, acting out a little secret mission in the woods. But with the power of the Internet, that little mission can be amplified to anyone looking, which makes the next part a bit disturbing.

Outside a tidy white house, the screen goes dark. It’s Gene Rosen’s house and Hunt hides the camera to surreptitiously record audio. When he answers, Hunt introduces himself: “My name’s Brendan from WBAI. I have a little radio show and TV show.”

“WBAI in New York City?” Rosen asks inquisitively. “Yeah,” one of the two friends responds. “It’s a neutral blog we’re doing, we’re sort of trying to play both sides, we’re not, you know …” the other says, before trailing off.

Rosen says he’s been through a lot already with the truthers and isn’t really interested in talking more. The two friends say they totally understand where he’s coming from, and agree those truthers are terrible. Rosen declines the interview (as he did for this story, citing a desire to avoid encounters like this).

Jeffrey Pyle, a First Amendment lawyer with the Boston-based law firm Prince Lobel, tells Salon that while Connecticut requires all parties to consent to being recorded over the telephone, only one person needs to consent in person, so the recording is probably kosher.

They return later that night. “You can get a close look at Gene’s house,” he says zooming in on the white house, while remarking about nearby landmarks and road names, making the location easily identifiable. He continues to “snoop around,” but eventually backs off to avoid raising suspicion.

The two friends are hardly intimidating — Hunt proactively asks a police officer if he’s not allowed to be where he’s standing at one point in the video — but the video suggests the Truther conspiracy is more resilient than many suspect, and how this kind of “just asking questions” could lead to unintended consequences.

Hunt and I went back and forth in an interview over many rounds of emails. After I sent him some questions, he posted them on his website with answers, and asked commenters to edit them before he’d send them back to me. He later seemed to get cold feet.

In the publicly posted answers on his website, he started off eager to talk, saying, “I think there are some real discrepancies in the official narrative, which deserve to be looked at by mainstream media outlets. I would be more than happy to discuss them with you.” That quickly turned to suspicion: “It has come to my attention that you’ve written several articles about Sandy Hook skeptics, not exactly portraying them in the best light.”

Asked about his interest in conspiracy theories, Hunt says he’s “suspicious of both mainstream and alternative media, and I try to make an informed opinion on current events by thinking critically about important issues. Some topics that I’ve been researching recently include the trial of Bradley Manning, and the U.S. drone bombing campaign in the Middle East.”

“I first started to get interested in the alternative Sandy Hook theories,” he explains, “when I saw the helicopter footage of police chasing someone into the woods directly in back of the school.”

The last time we checked in with the Sandy Hook truthers, the movement was flagging a bit after a meteoric rise in the month following the shooting.

But the theory has shown surprising resilience, spiking back up near its record high again and again in the last few weeks on social media. For instance, on February 19, a video purporting to show that victims’ families are “crisis actors” got social media 150 simultaneous mentions, according to Topsy, another claiming to be the “ultimate” hoax video got almost 200 a week later, and a third “official” video climbed even higher the next week. And it’s been climbing in the past week, since March 12. And this time, outside the gaze of the media, the interest seems to be driven by the conspiracy websites, not mainstream news reports.

David Mikkelson, the co-founder of the myth-busting website Snopes.com, tells Salon the Sandy Hook material is currently “warm,” if not the single most dominant topic he’s monitoring: “There’s a fair amount of interest, but there are many topics (e.g., Angolan witch spider, burundanga, Facebook privacy warnings) that are generating far more search/inquiry interest on our site right now.”

Will it ever go away? “I’d say, like all conspiracy theories, it’ll hang around for a while — holding less interest for the general public over time, but never going away completely,” Mikkelson explains. “I think a lot of the interest or belief is driven by the fact that we still know so little about the shooter and his motivations, so people naturally try to fill in the blanks (as they did with, say, the JFK assassination) by positing that the whole thing must have been part of a larger and grander plot rather than an act committed by a single person for no sensible reason.”

Indeed, the Hartford Courant excoriated officials in a recent editorial for “clamping down” on information. “Secrecy feeds into the whispers of those conspiracy theorists who believe that the police have something to hide,” the editors wrote.

After the Newtown town clerk was “inundated” by requests for death certificates of the children killed, lawmakers considered restricting access to the documents, but that only fueled the theorists and prompted a resurgence in activity on conspiracy message boards as people assumed there must be something to hide.

“We are being denied to see the death certificates to prove that children actually died in Sandy Hook. At this time, there are no actual photos of them dead, body bags, or videos of them in the school,” wrote one poster on LiveLeak. “How come for the first time ever, they are trying to cover up the Death Certificates?”

This cycle of conspiracy theory and government secrecy is typical, experts explained to me, putting officials in an awkward lose/lose situation when it comes to tamping down myths. If they release more information, it might be mined for inconsistencies with initial reporting, which is always spotty and often wrong. If they don’t release more information, it will be taken as proof positive that there is something fishy going on.

If Hunt’s material is any indication, this is what’s happening with Sandy Hook. In other words, the movement is far from over.