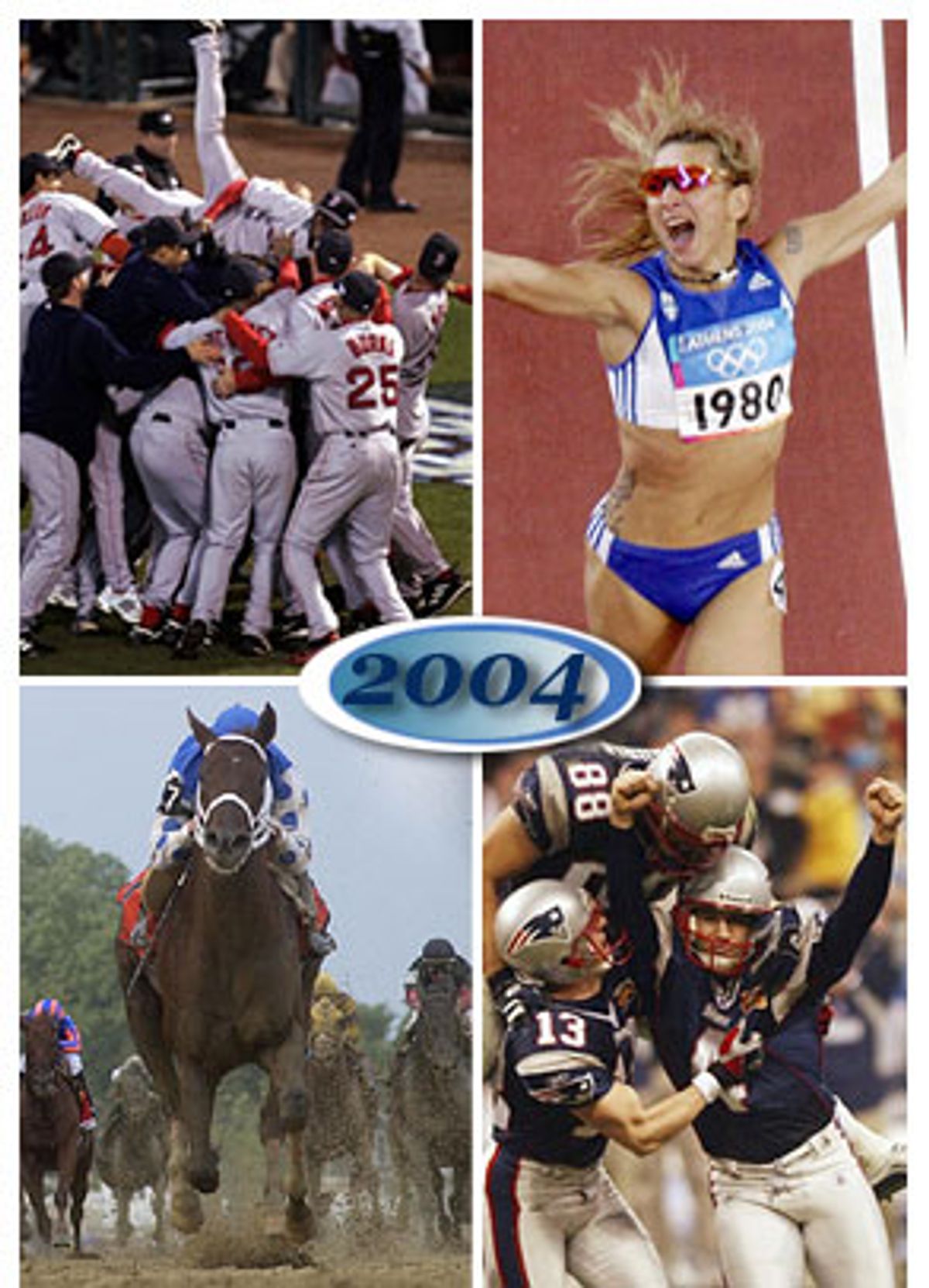

It was a year of teamwork and humility, hard work paying dividends, underdogs coming through, gracious winners, great champions and a little chestnut colt who came out of a second-tier barn and conquered a nation. Fans of the Boston Red Sox were finally rewarded for lifetimes of suffering and devotion. 2004 was a year when sports showed us everything it's so good at showing us.

And then there was BALCO. There were chairs and fists flying in the stands, an entire sport shutting down in a labor war and a transcendent NBA superstar shuttling between playoff games and a courtroom where he was facing rape charges. And there was the incessant drumbeat of corruption, deceit and exploitation that is big-time college sports.

Those are the things sports are good at showing us too. Best of times and worst, thrill and agony. Sometimes, especially during the Olympics, there was all of it in one day, in one second. In the end 2004 was just another year, only more so.

The NFL offered up the first, best vision of how sports oughta be, serving up a Super Bowl between a pair of blue-collar teams devoid of superstars and their attendant egos.

The New England Patriots were in the midst of what would become a 21-game winning streak achieved by excellent but not spectacular play on both sides of the ball. The out-of-nowhere Carolina Panthers were a no-name team given little chance to make the playoffs and no chance to get to the Super Bowl or beat the Pats. They did the former and nearly did the latter.

Unfortunately, that terrific championship game was overshadowed by the silly controversy over Janet Jackson's wardrobe malfunction, the first of two brouhahas involving football-related entertainer nudity during 2004. But it set the tone for the year in North American team sports.

Springtime found the Calgary Flames and Tampa Bay Lightning playing for the Stanley Cup, not the richer, more glamorous Detroit Red Wings or Colorado Avalanche against the Philadelphia Flyers or Toronto Maple Leafs. Though the Lightning had some stars, the marquee player of the series was Jarome Iginla, leader of the heavy-underdog Flames and maybe the best player in hockey, but at heart a hard-nosed power forward who grinds and grinds, outworking his foes.

The Stanley Cup Finals, which the Lightning won in seven games and which sparked an outpouring of love, partying and flashed breasts on the eventual losers' behalf in Calgary, went a long way toward making people forget the year's ugliest on-field incident in any sport, Todd Bertuzzi of the Vancouver Canucks attacking Steve Moore of the Colorado Avalanche from behind during a game, breaking three vertebrae in Moore's neck among other injuries.

Over the weekend there were reports that Bertuzzi, who faces assault charges in British Columbia, may avoid them by settling with Moore. He was also banned from playing in Europe by the International Ice Hockey Federation.

While the Finals generated some good feeling, it was tempered by fans' assumption that the NHL would shoot itself in the foot by locking out the players in September over the issue of a hard salary cap, which team owners insist on and players refuse to accept. That did happen, and the 2004-05 NHL season is in the process of being wiped out.

A few weeks after the Lightning skated with the Cup the Detroit Pistons won the NBA title, beating the Los Angeles Lakers, who were as much a fantasy as they were a team. The Pistons were a lunchpail gang, with a retread point guard, a head-case power forward and a 6-9 center, winning with defense, teamwork and hustle, what coach Larry Brown called "playing the right way."

The Lakers had three of the greatest players of all time, plus another likely future Hall of Famer, and one of the two most successful coaches in league history, and like the haughty private-school team in some teen movie, they went down in flames, squabbling and sniping and blowing apart completely within days of their defeat.

Coach Phil Jackson was pushed into retirement, Shaquille O'Neal was traded to Miami and Gary Payton to Boston, and Karl Malone entered a sort of not-quite-retired limbo. That left Kobe Bryant, who still faces a civil suit in the rape case that had him jetting between the hardwood and the courthouse, finally the undisputed leader of what's now no better than a marginal playoff team.

Bryant and his former comrades have been feuding publicly ever since, with the latest blowup being Bryant's accusation that Malone had made a pass at Mrs. Bryant, Kobe getting little public sympathy for his attempt to defend the sanctity of his marriage.

Meanwhile, LeBron James, the high school overachiever turned NBA rookie who was the biggest story of 2003, just got better and better. He followed his Rookie of the Year performance with some dazzling play in his limited opportunities with the Olympic team, coached by Brown, who mostly kept James on the bench. Now in his second NBA season, James has his Cleveland Cavaliers in second place in the Eastern Conference and is making a good case that he isn't just Michael Jordan's heir apparent, but his actual heir.

But the biggest heartwarmer, the real stuff of Hollywood, came in the World Series, which the Boston Red Sox had not won since that long-ago age when they dominated baseball thanks in part to their star pitcher, Babe Ruth.

The Red Sox had a higher payroll than any other team except the New York Yankees and employed such sparkling talent as Curt Schilling, Pedro Martinez, Manny Ramirez and David Ortiz. Just before the season started they had tried and failed to acquire the game's highest-paid player, Alex Rodriguez. But their 86 years of futility, their rivalry with the über-rich Yanks -- who ultimately landed A-Rod -- and their camaraderie and goofy, sloppy, hairy charm allowed the Sox to come off as a bunch of everyman heroes just like the Patriots, Pistons and Lightning.

Schilling, a hero of the 2001 World Series for the Arizona Diamondbacks, pitched twice in the postseason on an ankle so badly injured it literally had to be stitched together by team physician Bill Morgan before each game in a radical and risky surgical procedure.

Schilling beat the Yankees in Game 6 of the American League Championship Series, a for-the-ages comeback in which the Sox dropped the first three games, then won the next four, an unprecedented feat in baseball. Then he beat the St. Louis Cardinals in Game 2 of Boston's World Series sweep. It was the stuff of legends.

Within six weeks, Martinez had signed as a free agent with the Mets and blasted Schilling, manager Terry Francona and boy-wonder general manager Theo Epstein, and the Red Sox had fired Morgan and were trying to trade Ramirez. So much for legends and Hollywood endings.

2004 began with similar rancor in the form of fans and the commentariat bickering over which two from among three teams -- Southern Cal, Oklahoma and Louisiana State -- should play in college football's Championship Game. The Bowl Championship Series formula spit out Oklahoma and LSU, stiffing USC, the team that had topped the "human" polls of sportswriters and coaches, which make up a part of the BCS equation.

The controversy forced the BCS -- a coalition of the six major conferences, Notre Dame and the four biggest bowls -- to rejigger the rules to give more weight to the polls. And so 2004 ends with rancor in the form of fans and the commentariat bickering over which two from among three teams -- Southern Cal, Oklahoma and Auburn -- should play in the Championship Game. This time it'll be Oklahoma and USC tangling in the Orange Bowl Jan. 4. Next year there'll be more rejiggering, no doubt.

But arguments about who should play for a football title are good for business and hardly a problem for the NCAA. Not so the steady stream of reports about what a cesspool the enterprise is.

Early in the year there were allegations that the University of Colorado used sex and alcohol to attract football recruits and fostered a hostile atmosphere that led to multiple sexual assaults by football players. Late in the year came stories of "thousand-dollar handshakes" and no-work jobs at Ohio State. In between, not to mention before and after, there was seemingly a new chance every week to view the inner workings of the big-time college sports sewer, an operation built on the lie that "student-athletes" aren't professionals in a billion-dollar business, but students taking part in extracurricular activities.

Occasionally the cheating is so blatant it's amusing. An exam that Georgia assistant basketball coach Jim Harrick Jr. gave "student-athletes" -- the NCAA won't call them "players" because that sounds like a job title -- in his Coaching Principles and Strategies of Basketball class in 2001 came to light this year, with such brain teasers as "How many points does a 3-point field goal account for in a Basketball Game?" More often, it's just depressing.

What's needed to make us forget such ugliness is a genuine hero, someone we can root for unabashedly, and 2004 provided a few of those. Roger Federer dominated men's tennis, and not with a boringly overpowering serve but with shot making.

Maria Sharapova, a 17-year-old Russian-American, upset Serena Williams to win Wimbledon. She rose from No. 32 to No. 4 in the rankings and brought back some of the dazzle that had been missing from women's tennis in the last couple of years as Williams has fought injuries and a seeming lack of focus.

Diana Taurasi, one of the greatest women's college basketball players ever, if not the greatest, led her UConn Huskies to their third straight NCAA title, this one coming the day after the UConn men had won the championship, the first such parlay for one school.

Taurasi, who is reminiscent of Magic Johnson both in her game and her open, engaging public persona, then became the youngest member of the U.S. Olympic team, which won gold. The first overall pick in the WNBA draft, Taurasi averaged 17 points a game, fourth in the league, and easily won the Rookie of the Year award as her Phoenix Mercury improved from 8-26 to 17-17.

And no discussion of sporting heroes in 2004 can be complete without a mention of former Arizona Cardinals safety Pat Tillman, whose heroism came not on the field, but when he left it three years ago to join the Army Rangers. Tillman was killed in action in Afghanistan in April. Whether his was a hero's death can be debated. That he was an unusual, admirable man cannot.

But no hero, no champion, nothing could make us happily forget everything ugly and awful in the world like Smarty Jones, a rambunctious little chestnut colt from that non-hotbed of thoroughbred breeding, Philadelphia, who captured the imagination of non-racing fans like no horse since the three Triple Crown winners of the '70s, and maybe like none since the first and greatest of those, Secretariat.

Smarty Jones was small and had a sprinter's pedigree. As a 2-year-old he'd fractured his skull and an eye socket when he reared up in a starting gate during training. His 77-year-old, emphysema-suffering owner, Roy Chapman, had never taken a horse to the Kentucky Derby. Neither had his trainer, John Servis, or his jockey, Stewart Elliott.

There was every reason to believe the long, tough Triple Crown races would eat him up, but he went off a 4-1 favorite at Churchill Downs and won the Derby. Two weeks later he demolished the field at the Preakness Stakes, pulling away down the stretch in a moment slightly reminiscent of Secretariat's legendary Belmont run, winning by 11 lengths.

America's Smarty fever redlined, and a record crowd, more than 120,000 strong, showed up at Belmont Park to watch him try to become the first Triple Crown winner in 26 years. But the Belmont's mile and a half was finally too much for our hero. He gave up the lead to a 36-1 longshot named Birdstone and lost by a length.

It was such a stunning, disappointing result that Birdstone's jockey, Edgar Prado, actually apologized for winning. Though Smarty Jones' handlers promised he'd keep racing as a 4-year-old, he was quickly retired to stud, a common move that makes financial sense for the participants but robs fans of the excitement of following the career of an established champion. Too bad, current and potential thoroughbred racing enthusiasts.

Strange as Prado's apology was, it was also just one of many examples of a victor's graciousness in these chest-pounding, ungracious times. The U.S. women's basketball, softball and soccer teams all won gold medals at the Athens Games, and their esprit de corps and grace in victory made them -- always implicitly, sometimes explicitly -- a stark contrast to the men's basketball team, which stumbled to the bronze amid a hail of criticism at their lackluster, selfish play and prima donna attitude.

Much of that criticism was misplaced. The American men's real problem was that they were a poorly constructed team, an all-star roster made with an eye toward NBA marketing rather than winning in international play and handcuffed by the fact that most of the top players invited to play had declined.

Still, they left the world with the impression that Americans can't compete with the rest of the world, even though, for example, the dominating star of the gold-winning Argentine team, Manu Ginobili, while a nice player, is hardly among the NBA elite back in the States. There's little doubt the Detroit Pistons, all of whose key players were American, could have wiped the floor with the Olympic field.

For a long time Americans couldn't compete with the rest of the world in soccer, and while the men are still trying to climb, the U.S. women have been at or near the top for a decade and a half. The team that captured gold in Sydney was a valedictory for the "Fab Five" nucleus -- Mia Hamm, Brandy Chastain, Kristine Lilly, Julie Foudy and Joy Fawcett -- that had led the Americans to the first Women's World Cup in 1991 and the first women's soccer Olympic gold in 1996, along the way becoming the most important women's sports team in the world. If you have a daughter with a soccer ball, they gave it to her.

As usual, the Olympics had no shortage of uplifting stories. There was the improbable run of the Iraqi men's soccer team, the touching retirement of wrestler Rulon Gardner, the jaw-dropping gold-medal kick of Moroccan middle-distance great Hicham El Guerrouj, denied the gold he'd been favored to win in each of the last two Olympics.

Even gymnast Paul Hamm's struggles with himself, the judges and the crowds were inspiring in their way. Whatever you think about whether he deserved his gold medal in the all-around, there's no denying the kid really knew how to deliver in the clutch.

There was swimmer Michael Phelps, not only living up to the pre-Games hype by winning six golds and two bronzes but giving up his spot in the 4-by-100-meter relay final to teammate and rival Ian Crocker, who otherwise would have been out of chances to win a gold medal. The team did win. Phelps' shine was dimmed a bit last month when he was charged with drunken driving.

Fani Halkia of Greece came out of nowhere to win the 400 meters in front of a delirious home crowd, making up somewhat for the Greeks' bitterness over sprinters Kostas Kenteris and Katerina Thanou withdrawing from the Olympics after missing a drug test.

And so it went, in the Olympics and elsewhere. For every stirring victory, a dreary tale.

Lance Armstrong won his sixth straight Tour de France -- amid continuing whispers of doping -- and former teammate Tyler Hamilton, known as a paragon of virtue, tested dirty for an illegal blood transfusion and faces suspension. He vehemently maintains his innocence and will plead his case before the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency.

Eric Gagne, Ichiro, Johan Santana, Vladimir Guerrero, Roger Clemens and Barry Bonds had spectacular baseball seasons, and Milton Bradley melted down repeatedly and raged at home fans, slamming a beer bottle at their feet. Rangers pitcher Frank Francisco threw a chair into the stands in Oakland, breaking a fan's nose.

But such incidents pale in comparison to the revelations about steroid use in leaked grand jury testimony in the BALCO case. Bonds admitted that he'd used substances known as "the cream" and "the clear," provided by his friend and trainer Greg Anderson, one of the defendants in the case resulting from a federal investigation into the Bay Area lab run by Victor Conte. Bonds claimed he didn't know the substances contained steroids. Jason Giambi of the Yankees, a former MVP, admitted using steroids too.

That story shares the headlines at year's end with another equally grim one: the aftermath of a hideous fight at a Pistons-Indiana Pacers game in Detroit last month that saw players wading into the stands and swinging at the customers.

Ron Artest of the Pacers was suspended for the season and teammates Jermaine O'Neal and Stephen Jackson got 25 and 30 games. Others were suspended for shorter periods, and those three, plus teammates David Harrison and Anthony Johnson, face criminal charges, as do seven fans.

The day after the brawl in Detroit, a riot broke out on the field among football players toward the end of a South Carolina-Clemson college game, giving rise to a feeling that the sports world was starting to come apart at the seams.

It's a time of hand-wringing as the year closes. Listening to the chatter and reading the typists' words it seems that fans can't go to a ballgame with any assurance that what they're seeing is genuine, not chemically enhanced, and that they won't find themselves throwing fist in the box seats with some enraged behemoth from the visiting team.

There are real concerns and these are sometimes ugly days in the sports world -- as all days are. But these are also the days of miracle comebacks, underdog runs and good old-fashioned values being rewarded with championships. Throw 2004 on the pile as another one of those years, good with the bad, just like life. And then just a little extra.

It was Ron Artest but also Smarty Jones. It was Todd Bertuzzi but also Diana Taurasi. It was the NHL lockout but also the Boston Red Sox. It was Barry Bonds but also ... Barry Bonds.

Shares