In a recent Salon article, Noah Berlatsky argued that to be a successful writer, while one might need “work ethic, knowledge, skill, perseverance... none of them is as important as the one, single most important thing. Which would be luck.”

Berlatsky’s piece suffers from what Daniel Dennett calls deepities: “A proposition that seems both important and true — and profound — but that achieves this effect by being ambiguous.” That is, if we take Berlatsky’s assertion as he intended it, hyperbolically, it is banal: We all know that luck affects us in all parts of our life. And if we take it at face value, it is manifestly false. Does Berlatsky really believe that luck is more important than work ethic, knowledge, skill and perseverance?

That's a hard case to make, although it does correctly note that those latter qualities alone (work ethic, etc.), while to varying degrees necessary for success, are too often insufficient. So Berlatsky wasn't wrong there, he just picked the wrong culprit. The real problem in writing isn’t luck, it’s money.

Reading, writing and thinking are all tasks that are nearly impossible to cultivate while performing manual labor. As Plato first noted, when discussing education, “sleep and exercise are unpropitious to learning,” and therefore students should avoid intense exercise as they pursue educational endeavors. Writing is what Veblen would call “conspicuous consumption,” a task primarily done by a “leisure class” uninhibited by manual labor.

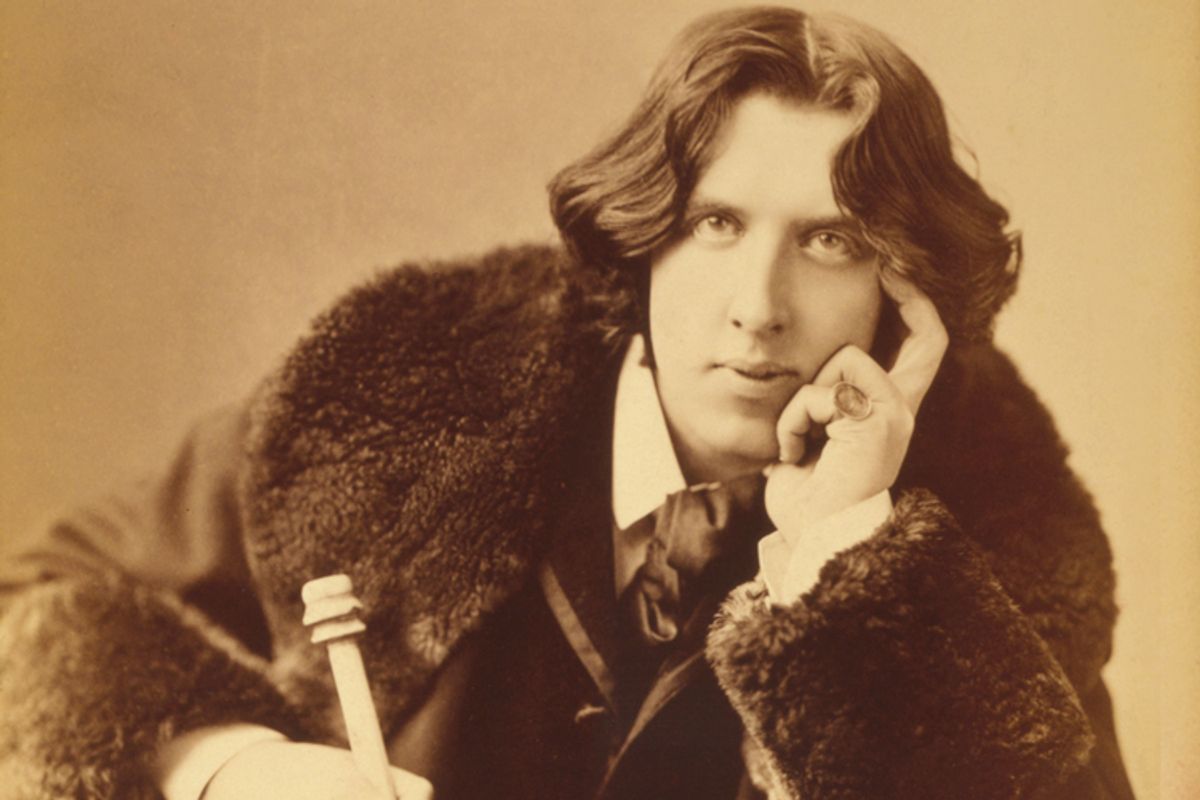

As Oscar Wilde wrote, “under existing conditions, a few men who have had private means of their own, such as Byron, Shelley, Browning, Victor Hugo, Baudelaire, and others, have been able to realise their personality more or less completely. Not one of these men ever did a single day’s work for hire. They were relieved from poverty.” Because Byron and Baudelaire were free from the need to perform physical labor, they could invest their time in culture. In contrast, the poor, “having no private property of their own, and being always on the brink of sheer starvation, are compelled to do the work of beasts of burden, to do work that is quite uncongenial to them, and to which they are forced by the peremptory, unreasonable, degrading Tyranny of want. These are the poor, and amongst them there is no grace of manner, or charm of speech, or civilisation, or culture, or refinement in pleasures, or joy of life.” The luxury of comfort is still denied the poor and working class and it’s difficult to read Shakespeare after hours of drudgery. Far easier to drink a beer and watch the game. In his book, "Masscult and Midcult," Dwight MacDonald notes that “the great cultures of the past have been elite affairs.”

In a recent interview with Longform magazine, New Yorker staff writer Evan Ratliff said, “I don’t think it’s feasible to work a full-time job and be able to do this type of reporting … it really requires dedicated time.” And time, as we all know, is money. Success at writing means taking unpaid internships, low-paid fellowships or writing almost for free for years.

Mark Twain once said that success in writing requires one to "write without pay until somebody offers pay. If nobody offers within three years, the candidate may look upon this circumstance with the most implicit confidence as the sign that sawing wood is what he was intended for.” To do such writing (while paying off debts from Columbia Journalism School) without some side source of income, means, most likely, coming from an upper middle-class or affluent background with parents who can bankroll you. I’ll state the obvious: There aren’t many poor writers. How could there be? How does one practice writing in abject poverty?

This dynamic pervades even socialist thought. Gramsci, the poorest of Marx’s early 20th century interpreters, only wrote a sustained historical and theoretical critique when he was imprisoned. And it’s no coincidence that the great expositor of working class misery, Engels, was the son of a wealthy capitalist. The working class had neither the time, nor education, to consider their own plight. It’s no coincidence that the greatest thinker to address capitalism, Karl Marx, died destitute and was sustained only by patronage of Engels. Sadly, as the Marxist tradition grew divorced from the working class, its expositors grew increasingly obtuse, with Adorno, Della Volpe and Althusser increasingly unreadable. While Marx intended his work to be accessible to the working class, the later Marxists seemed to have rather the opposite intentions. As Perry Anderson notes, “the whole tradition swung increasingly away towards bourgeois culture.”

The “great thinkers” of the past were, for the most part, were those wealthy enough to think and be heard — Montesquieu, Smith, de Tocqueville, Keynes, Schopenhauer, Hegel, Freud, Darwin, Huxley. Pick a thinker, and you’ll find a wealthy family behind them. Much the same is true today.

Shares