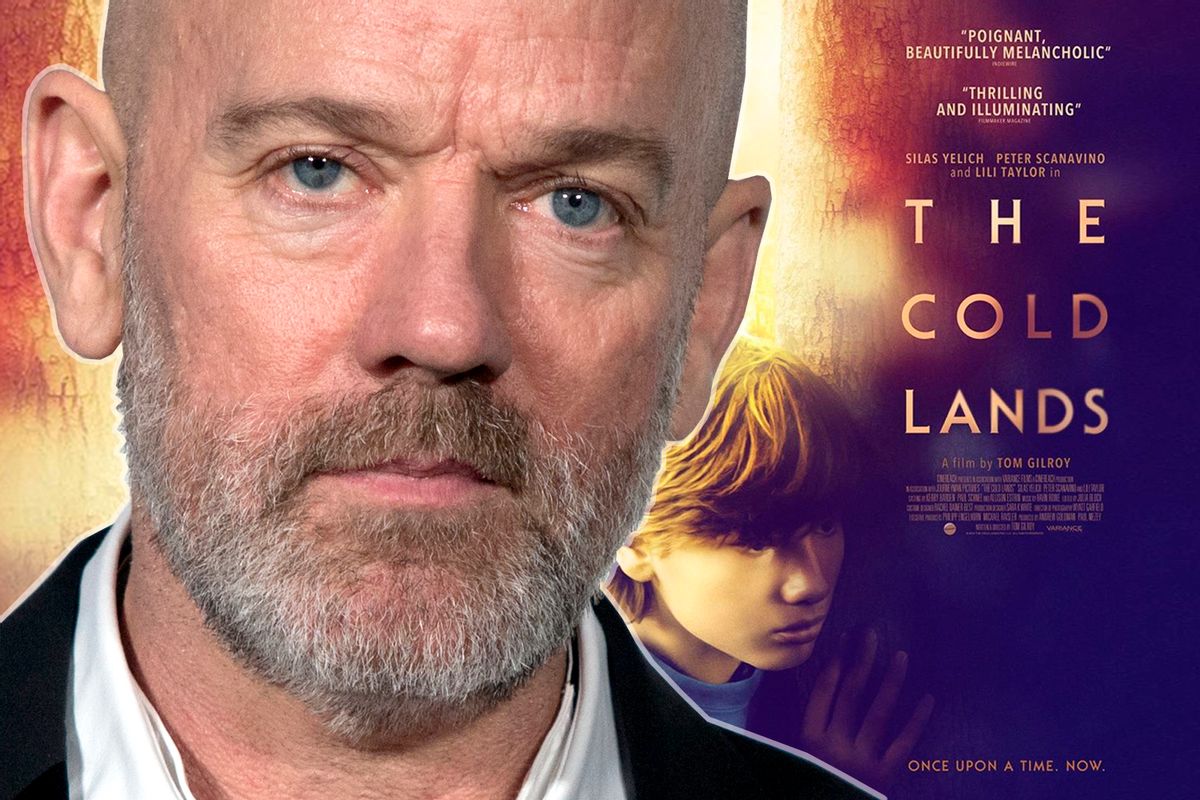

Michael Stipe and Tom Gilroy have been friends and collaborators for more than three decades now, on an amazing range of film, music and political projects.

And that long, close friendship helped inspire Stipe to create his first music since R.E.M. disbanded in 2011 -- which Salon premieres exclusively today in the above video clip.

It's a really sensational soundscape that accompanies bonus footage from Gilroy's new film "The Cold Lands," which is now available to stream on video-on-demand.

Over the last three years, Stipe has focused on sculpture, silkscreens and more visual and tactile art. Many of the very cool pieces fill his New York apartment, where Stipe, Gilroy and I met last Friday afternoon to discuss the music -- why he wanted to do this piece and whether there will be more -- and other projects he's been up to over the last three years.

Did you have any choice in selecting the footage? It's amazing how it feels like you -- it's this edgy, sexy, shirtless footage, and it really captures a different sense of the film. There are secrets being whispered by the water, and these images of water have run through your songs over the years, whether "Nightswimming" or "file under water."

Michael Stipe: Tom is one of my best and oldest friends; we’ve known each other for 32 years. I knew what he was putting into this film. And I knew, symbolically, what certain things meant to him. So I wanted the peacock and I wanted a scene at the waterfall. I actually didn’t care if there was talking. If there were scenes where there would be dialogue, you’re seeing their mouths move, but nothing’s happening. In fact, I find that kind of thrilling. It makes you wonder what’s happening.

Tom and I just batted back and forth a few things that he knew he had a lot of -- which was leftover footage of the river, leftover footage of the waterfall and then the peacock. Just knowing Tom and knowing symbolically what those moments meant to him as a creator of the actual film, those were the ones that I gravitated towards. In terms of the cut, he cut it together with his editor. I had no say in that.

So how did you start thinking about writing and performing the music? You've done hundreds of vocal melodies, but this feels like a first.

I went to Andy LeMaster (Now It's Overhead), who’s one of my favorite songwriters. He’s a tremendous producer, he’s a tremendous person. I know I work well with other people -- to have someone to bounce something off of works for me, and I don’t actually write music. I wrote melodies and I tend to write along to other people’s music. That’s what I’ve done most of my career as a musician.

I went to Andy knowing that if I painted myself into a corner, he’d pull me out -- and also that he’d be more than a neutral engineer/collaborator to work with. We work really well together. This is, in fact, the first thing that I’ve done musically since R.E.M disbanded. So, of course, I wanted it to be for something that meant a lot to me. That was important.

You guessed my next question. That knowledge -- that this was the first music since R.E.M. -- must have put some extra pressure on you.

Yes, of course it did. But I knew I wasn’t going to sing, so that made it easier.

And you anticipated that question, too. Why not?

I just didn’t want to.

Tom Gilroy: Also, originally, I didn’t even go to you, if you remember. Because you had been talking so much about visual art and your sculpture. I was talking to you about help and approaching other musicians, and you were like, ‘What about me?’ And I was like ‘duh!’ But I didn’t think you wanted to do that anymore.

I thought the same thing. When Tom told me you'd made this, I was very surprised.

Michael Stipe: Just to go there: I’m a terrible painter. Just to put that in capital letters. And I know that. But this was more like an oral painting in a way because I didn’t have to use my voice. I didn’t have the pressure of writing a lyric or expressing a feeling or emotion through my voice. I could do it through instruments.

That's an entirely new pressure, though! Perhaps a fun new pressure.

It’s exciting. I ended up writing four different song parts and then putting them together.

This really has groove. What did you want it to sound like -- did you have something specific in mind?

I tried to bring groove. And Andy is an excellent bass player, so we were able to do something like Tom Verlaine, who I actually bumped into on the street the other day. It was unbelievable. It was like, ‘Tom!? It’s Michael, hi!’ It’s been ten years since I’ve seen him.

Tom Gilroy: It’s interesting that you mention Tom because I wouldn’t think of that.

Michael Stipe: My interpretation of Tom Verlaine and how he plays to other people’s work or creates parts is that he doesn’t want to fall into a clichéd blues riff. He’s working to avoid that. He doesn’t want to play jazz. Like Peter Buck would say, ‘You only play what’s absolutely necessary.’ And that takes every ounce of your energy as a musician. You’re a musician, you’re a player; you know what you’re doing. You could play along -- but sometimes it’s not essential to the thing moving forward.

Tom Gilroy: That’s why I like film, because you only leave what’s necessary.

Michael Stipe: We didn’t watch the footage as we were cutting the music together at all. I think I let Andy see it twice before we started -- and then we didn’t look at it until the musical piece was completely done and mixed. And I think we wound up extending something by five seconds.

One of my great mentors in art is James Herbert. Jim used to say in class that his belief was you can take any visual and any sonic element and combine them -- and the human brain would make it work together.

Pink Floyd and "The Wizard of Oz."

Right. There are moments there at the very beginning where he’s shaking his hair and it looks like a Hollywood studio sat around for six months deciding that’s exactly the sound that should come in after. But as it happens it just works beautifully together. And there’s almost a theme to the introduction of the peacock into the piece.

Tom Gilroy: I thought about that exact thing when I first saw it. I was expecting it to sound awesome, but while I was watching it and scoring it, how it was going together was incredible.

Michael Stipe: It was a marathon two days or three that we worked on it. But in the end, when we finally put it up with the visual, we were laughing like little children, saying ‘What the fuck! This actually works!’ I thought we were going to have to cut it, but we did have to extend it five or seven seconds with the drums. Actually, I played the drums, which was not a first, but…

You played the drums?

Well, the drums are electronic so it wasn’t that hard. But I knew where I wanted them to land and we made it work.

So Andy's on the bass. You also did the keyboards?

Andy plays the bass because I can’t play an instrument to save my life. I do play the keyboards. And his studio is near the train tracks, so there’s the train, which is very close to where both of us live. We hear the train when we’re on the phone talking to each other. I can hear it over the phone and across my back fence at the same time. So the train made it in; that’s a little part of Athens or whatever. The creation of the song is treading the same territory as the creation of the inspiration for the song, which is "The Cold Lands." It’s very deeply American and very much about how beautiful and how flawed we are.

So why this time for a first a musical portrait?

I spent the last couple of year trying to surprise myself and embark on journeys that are outside my comfort and experience. And so, why not do it? What’s stopping me from doing it? The only thing I can do is fail, at the very worst. Or insult someone, and I don’t think that happened.

Have people been nervous about asking you to do music?

No, people have asked. I said ‘no’ over and over again.

Wanting the focus to be on new things?

I have a pretty good sense of what people are asking me for when they ask me to participate in something musical. It’s not what I wanted to do. This is something that was actually outside of my realm of experience and something that interested me. And, you know, it wasn’t the follow up to "Man on the Moon."

Why did you want the peacock?

I knew what the peacock meant to Tom. And I thought the footage was beautiful and I knew that in the finished film the timing of the peacock -- and how it plays into the larger story of "The Cold Lands" -- is essential, deeply poetic and for me, very, very powerful. So I knew that Tom had shot a lot of the peacock. I knew that it existed in his life outside of this film.

We made a whole record about summer (R.E.M.'s "Reveal") and it’s not a record a lot of people loved. But over and over again, I was referencing dragonflies, and I remember reading all these reviews by people saying I was using this mythological creature or using that as allegory to something else. And, in fact, I have a lot dragonflies in my backyard, and I was writing in the heat of summer.

So, Tom has a peacock in his life and I know what that means to him in real life. And I know metaphorically or allegorically what it means within the construct of "The Cold Lands" and to the trajectory of this boy’s story and his life. It’s very important. I like the big symbol. I want to go for that, so I did.

Was there anything else inspiration-wise in mind that you were thinking about?

I just wanted to honor the ask and then the film, because I really loved it. Without Tom’s influence, I probably would have done something much quieter. But I knew that he wanted something that had a beat, so that was great because it really pushed me.

I’m happy with where it landed. It felt to me like a great first project.

First project -- does that mean there will be more like this?

I don’t know. Let’s put a giant parenthesis around that.

It’s like photography for me right now. I think photography at one point represented something very different from what it represents for me in 2014. In 1975, photography was something very, very special to me. It still is, but it’s become a means to an end or a part of something much bigger. So I think music will most definitely be a part of my future output. I hope it is. But it’s going to run through a very different circuit, I would expect. I love music. I think it’s an immensely moving form for me, but how do I apply that to where I am now?

It has to be hard to figure out. You have something that’s important to you, but something that you’ve been so well known for, for so long. To step away and put a toe back in…

This is not what people want to hear from me. But that’s want I want to offer, so…

You definitely knew that there was no way that you were interested in having words on this? Or singing?

No, no. If there was a singer, it wouldn’t have been me. I would have found someone. That’s not just being ornery. It’s just that I don’t want to do it right now.

Tom Gilroy: You already did it pretty well.

Michael Stipe: I did it and I did a really good job of it. Thank you. I’ll accept that meager compliment.

I’m sure this will spark speculation about more music. This is the first song since R.E.M. disbanded…

I wouldn’t call it a song. I’d call it a soundtrack or a musical piece. Yeah, of course it’s a big deal, but so is my friendship with Tom and so is "The Cold Lands." It was something I wanted to do and I wanted to stretch and challenge myself a little bit. And I do love music.

Miss it at all?

No. Music is like emotion. It takes such a huge amount of effort and headspace to move around. And I can step away from that for several years and be very happy.

We were in Athens in November for Jim McKay's film festival, and we were both at the 40 Watt when Bill Berry and Mike Mills joined Peter Buck on stage. I saw you lurking in the back…

I wasn’t lurking! I like to lean when I watch music.

Swerving, then! I imagine a lot of people were wondering "What is Michael thinking while watching this?"

No, they were walking up and asking me when I was going to get up on stage and I said, ‘I’m not. I’m here to see my friends do what they love to do.’

Tom Gilroy: You're a great lyricist. I wonder, what does the brain do when you stop writing? Where do those chromosomes go when someone stops doing that?

Michael Stipe: Into breath. That’s a great question. More objectively and not about us or me, I think it’s about creation and the urge or the need to create, and that’s something that will never leave me or you. So if it’s not a medium that you’re comfortable in or know well, maybe it’s one that you’re uncomfortable in and don’t know that well. Maybe it just shifted enough to be applied elsewhere.

Shares