Many states have in recent years raised the threshold value of stolen money or goods that qualifies as a felony, meaning that the pettiest thieves no longer face the prospect of a year or more prison. Critics warned that a lack of deterrence would entice rationally-calculating criminals to pilfer private property en masse. According to a new Pew Charitable Trust study, they were wrong.

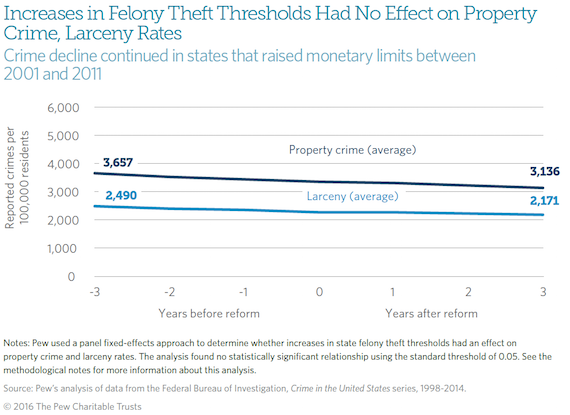

Pew looked at the crime rates in the 23 states that raised their felony theft thresholds between 2001 and 2011 and found that the changes had no impact on property crime and larceny rates; that theft rates in those states declined at the same rates as those states that did not change their thresholds; and that the limit of the higher threshold, whether to $500 or $2,000, made no difference.

Thresholds still remain quite low in many states, however, and inflation has ensured that these laws only get harsher. Take Massachusetts, which last raised its threshold from $100 to $250 in 1987, according to the Boston Globe. While stealing a $400 iPhone in every other New England state is petty theft, it’s still a felony in Massachusetts. Some legislators now want to raise the bar; predictably, the Retailers Association of Massachusetts takes a skeptical view, contending that the fines available would be “an inadequate deterrent against future theft.”

But that, says University of California Berkeley public policy professor Steven Raphael, is exactly the sort of contention that this Pew study proves to be false: The deterrence effects of harsh penalties have been exaggerated.

This Pew study, while picking off the low-hanging fruit of small-time theft, sends a message to policymakers that they can keep the public safe and secure without excessive punishment. It's an important message to send, because any move toward decarceration prompts un-empirical warnings to the contrary. Take California, where Prop 47, approved by voters in 2014, generally raised the felony theft threshold and reclassified non-violent felonies like drug possession as misdemeanors—and law enforcement is already screaming without a factual basis that it has led to an increase in crime.

The truth of the matter is this: Locking people up for extremely long periods of time has led to a human rights catastrophe in the United States and failed to do much in the way of crime prevention.

The study didn’t address the impacts on offenders. But raising the theft threshold is likely keeping some small-time thieves out of prisons, says Raphael, and perhaps diverting many more out of local jails and away from the quagmire of probation. It’s also likely reducing the collateral consequences for those who, say, commit a theft in their youth and later don’t have to contend with applying for jobs with a “felony conviction around their necks for the rest of their lives.”

Raising the theft threshold is an important reform. But keep in mind that small-time thieves never made up a large proportion of this country’s enormous prison population in the first place. “In some ways, the larceny theft changes nibble at the edge,” says Raphael. “It’s not going to make a huge dent in the country’s incarceration rate.”

To do that, we will have to take a hard look at harsh sentences for more serious crimes.

Shares