There is a scene in the 1994 movie, “Double Happiness” where a Chinese Canadian actress named Jade Li (Sandra Oh) performs a soliloquy from Tennessee Williams. It’s a rare example of seeing an Asian performer play a traditionally white role. In the 20-plus years since “Double Happiness” there have been far too few opportunity for Asian actors to have meaty or leading roles on screen. Not that there have been many opportunities for Asian actors to have lead parts before then.

The backlash for Asian American actors being excluded from leading parts has reached the breaking point this year with the hashtags #whitewashedout and the campaign #starringJohnCho, as well as a recent “New York Times” Sunday arts cover story about Asian American invisibility on screen.

The lack of inclusion or diversity in Hollywood certainly pertains to all minorities, but Asian male actors are particularly affected. For example, Asian men are almost never seen as romantic leads, though TV shows such as “The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt,” "The Walking Dead" and “Crazy Ex-Girlfriend,” as well as Aziz Ansari’s “Master of None,” are breaking this taboo.

Hollywood has created a Catch-22: There are no Asian superstars because they are not bankable actors, but there are no bankable Asian actors because there are no opportunities for them to become superstars. And Hollywood, if you are listening: one is not enough.

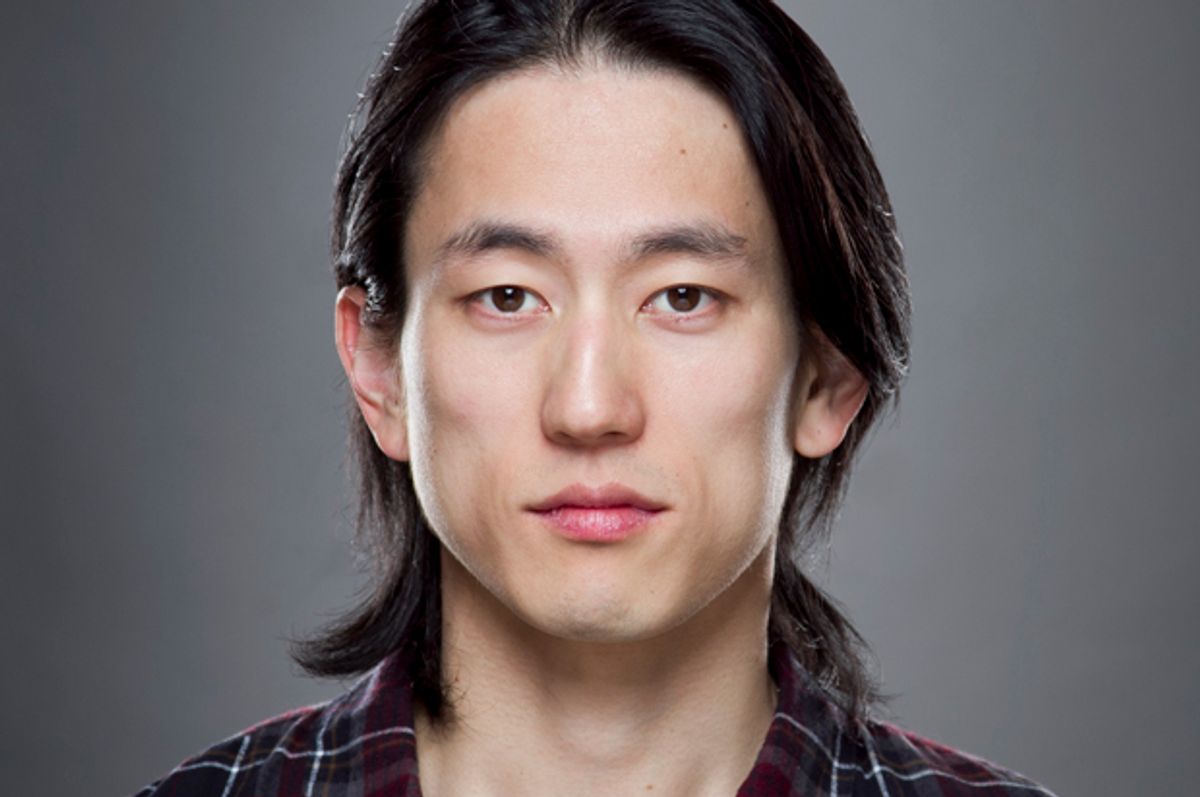

Jake Choi is an Asian actor who is just starting to make a name for himself. A versatile talent, he has a recurring role on TV’s “Younger” and has appeared in “Broad City” and “Gotham” as well as on film as a Korean TV newscaster in “Money Monster.” Choi recently played a gangster on NBC’s “The Mysteries of Laura,” and this summer he displays his romantic leading man chops in the feature film “Front Cover.” In this delightful romantic comedy-drama, Choi shows his deft comic timing as Ryan, a gay stylist hired to makeover a reluctant Chinese actor, Ning (James Chen). The guys’ relationship gets complicated for both many reasons, but the film, which is playing on the festival circuit this summer before opening theatrically in August, raises important questions about the representation of Asians in media.

In a recent interview via Skype, Choi chatted about his experiences as an Asian actor

Let’s start by discussing your background. Can you talk a little about your cultural identity?

When I was 14 until I was 18 or 19, I played on an Amateur Athletic Union team, the U.S. Asian Basketball Warriors. We had success playing top high school leagues. We’d always make the playoffs. A lot of people, even Asian people, don’t realize that a lot of Asians play basketball. There are some good ballers.

I found my identity through hip-hop music—Tupac—basketball, through Allen Iverson, and watching comedians like Martin Lawrence. I saw myself in them more than through mass media, or my family or classrooms.

Can you explain that further? Were Tupac, Iverson, and Lawrence appealing identification points because you didn’t have Asian role models in music, sports, and comedy? Or was there something else about them that you connected with?

Iverson was outspoken. There is a stereotype—but it has some truth to it—about Asians being the “model minority.” They keep to themselves and don’t want to speak out about anything—good or bad. In my household, maybe I wasn’t taught to keep my head down, but it was the implication. I didn’t vibe with it. Allen Iverson had tats and braids and was skinny, like me, but his stature was 7 feet tall. That’s more me. When I was a teen, and outside of my house, I was loud. I would get into altercations, and I would be outspoken. I didn’t want to be good or polite. Maybe it was boredom… In school, I did well in gym. I couldn’t get A’s in math and social studies and science. Maybe that was cool to not do well, but I wanted to make my parents proud. Instead of academia, I put my time in basketball. But with my mom, it was, “If you don’t make the NBA, I’m not proud.” As an actor, I have to get a three-picture superhero movie to make her proud. I was raised in a stifling and strict household. To see Allen Iverson and Tupac being outlandish, saying “I don’t give a fuck, I’m going to be me”—I love that. It’s all about self-perception.

There’s a line in “Front Cover” that the only popular Asian films in America are “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon,” “The Joy Luck Club,” and “Kung Fu Panda.” Most of the films that employ minorities fall into the category of “white savior” films, like Tom Cruise in “The Last Samourai” or Kevin Costner in “Dances with Wolves” and Sandra Bullock in “The Blind Side.” What do you watch?

I don’t watch movies much anymore. With TV, I’ll watch the pilot if I have an audition for the series. I do make a concerted effort to watch indie films that do have diverse cast, or that’s not telling a Eurocentric story, or is a “white people problem” film. Last night I was thinking, I wish there was a film or something like the equivalent of “Underground,” for Native Americans. I recently saw “Beasts of No Nation,” and needed a whole day to process that. There’s a psychological progression and arc to those characters. That was not a “white savior” film.

There is a line in the film “Front Cover” that Chinese parents want their children to grow up to be doctors. How did your family react to your decision to be an actor?

Before I was an actor, my decision to be a basketball player was more traumatic. My parents divorced when I was 11. My dad wasn’t around. My mother wanted me to be a doctor or lawyer because that was a way to make money. When I told her I was gong to be an actor, her response was, “Make sure you work hard.” I didn’t expect that. I was lucky to have a parent who is supportive. She said, “Do it big. Give it your all. I can’t see you working 9-5 or going back to school.”

I don’t often admit this, but when I was young, I played golf. I was really good when I was 10 or 11. My mom wanted me to further my golf career. She had aspirations that she wanted to live through me. I quit golf because it was boring, and I took up basketball. She thought I would be at a disadvantage [in basketball] to keep up with all the black and white kids. She was resentful because I quit golf because I was good. So for the next 5-10 years she’d mention Anthony Kim and Tiger Woods….

How did you get into acting?

It was a big shift. I did “Hamlet” when I was in school, but I didn’t catch the acting bug then like many actors do. I quit pursuing a career in basketball, and a friend suggested acting classes. I thought that was terrifying. I was dating an actress at the time, and she was taking classes, so I went along to one, and thought it was really dope. So I signed up for Lee Strasberg Institute. The more I took classes, the more I fell in love with acting and telling stories and playing different characters. I also read about the business.

Out of curiosity, were you the only Asian male actor in your class?

There was one other guy, Michael Kim, who transferred to my class. He was the only other Asian guy I met.

How difficult has it been to get a lead male role because of your ethnicity?

There’s probably a bigger chance of me winning the lottery than getting a lead male role in a big budget feature. I say that with no facetiousness at all. I’m lucky that I have great manager and agents. [He indicates that is represented by Ciro Entertainment and DDO Artists Agency]. They work so hard to pitch me for roles that have open ethnicity, and casting directors do call me in for roles that are leads of a TV series, or film. Film is rarer. TV is more common. I can see myself in the role, but you check “Deadline,” [an industry publication] and it’s usually a straight white male in that role.

I feel like studios or networks or producers will ask the casting offices, put “open ethnicity” for the breakdown so they don’t get criticized. It may be a SAG-AFTRA law. They bring in ethnic and non-ethnic actors they know, but once they do that, they cast it straight white, but ethnics get seen. My white friends who are actors say that I’m lucky that I got the audition, but I say, “Look who got the role!”

Can you describe any experiences with overt racism in your career and how you handled it?

I’ve not had any encounters as extreme as Ryan has in “Front Cover.” I went in for a commercial once and two directors were casting it. They didn’t know me and I didn’t know them. The moment I came in, they asked my name and ethnicity. By law, you can’t ask an actor his/her ethnicity, sexuality, or age. I paused, and I said, “I play Asian.” And they backed up and say, “OK, right, right…” After that, I had an attitude during the audition, but I ended up getting the job. I’ve had a few times where I’ve gone in for parts and it went well, but I was later asked if I knew any accents. My response was “Can you give me a good reason for that?" Then they would backtrack because they had no good reason.

Given the parts that are available to minority actors, do you deliberately seek out roles such as Ryan in a small, independent film like “Front Cover,” or do you want to focus on TV?

I think every project and role is case by case. My reps and I try to be as mindful as possible for the roles I submit to and what offers I take. In terms of being fulfilled as an artist, “Front Cover” is getting to play a three-dimensional character with psychological nuance. “Mysteries of Laura” pays better, and if you can play a character who is not a stereotype, and plays to a wide audience, that’s great. I’ve had to pass up a role because I had no interest in it, or it was a stereotype, or too small and I wanted to move forward. The roles I audition for are interesting and not defined by their ethnicity. That’s a testament to my reps and how hard they work. But there are fewer options. I’m not auditioning 24/7. We filter what I do, which is what I’d rather do than take any role.

Ryan styles Ning in “Front Cover” to present a sexy, appealing image because Asian men are rarely seen as sex symbols, much less leading men in this country. Can you talk about the lack of Asian male sex symbols and how you hope to change that?

Asian men in media are so desexualized and emasculated. I wish I knew why. Sessue Hiyakawa was one of the first Hollywood sex symbol in the early 1900s. He was an Asian male to open a Hollywood film with a female love interest. A lot of white American women would go see his films. I think a lot of the fear comes from that, where executives noticed that their women like this Asian guy, so maybe we should assassinate his character and sexuality. If you look at the timeline of his career, you can see a change. Part of it is fear and racism. And Asian woman can be with a white man because you’re not compromising white male sexuality and dominance and perception and straight white male insecurity. Asian men are emasculated. Ads do a better job than films to portray sexy Asians. When Jet Li and Aaliyah made “Romeo Must Die” they shot a kissing scene, but it was cut from the film. An Asian man kissing a woman is never shown, which is the emasculation.

What are your observations about how the media portrays Asian characters?

We are all human beings. It’s not like it won’t serve the story if the characters are not Caucasian. Asians are just as human and three-dimensional as everyone else. Mass media is not reflecting that. Asian men are not seen having a girlfriend or a boyfriend, but in real life you see Asians with black, white, Latino partners. The media portrays it in another way, and it changes perception of and for Asians and non-Asians. There are people who are conscious of it, but others are conditioned by it.

So, if you were given the opportunity to play any role, what would you most like to play?

A basketball player or a boxer. I’ve been boxing for a couple of years, though not to compete. You never see Asian boxers. Black, white, Latino, yes, but never Asian. Manny Pacquiao is Filipino. That would be so subversive and fresh. That would be good. You see martial artists in mass media that do kung fu, but not boxing. If you haven’t seen it, you can’t believe it. But once you expose something to people, it becomes real. It has to be seen.

Would you create your own opportunity to make an Asian boxing film?

Yes. It’s in the back of my mind. I do want to collaborate and create work.

Shares