The ongoing controversy surrounding Alabama’s Republican U.S. Senate nominee Roy Moore is unlikely to come to an end anytime soon, even if Moore decides to abandon his campaign. That’s largely because Moore’s rise to fame within conservative circles in Alabama and the nation is less about him as an individual than about the two political movements he has relied upon for support in his decades of political life.

In terms of ideas, Moore’s career as a state judge and public figure clearly indicates that he is a true Christian supremacist, a person who believes practicing Christians have more rights than other citizens. Moore believes that homosexuality should be illegal, he thinks Muslims should not be allowed to serve in Congress, his top donor was a longtime board member of a neo-Confederate organization and he hired John Eidsmoe, a far-right lawyer who has written voluminously on how to make American civil code compliant with biblical law.

While Moore’s long record of religious extremism makes him notable as a candidate for federal office, his views are really not that far removed from other influential figures on the religious right. Eidsmoe, for instance, hired future congresswoman Michele Bachmann to help him finish one of his books. He’s also enjoyed strong support from other Christian-right institutions and groups, including the Family Research Council.

Moore has been removed once from the Alabama Supreme Court and then suspended another time for his failure to abide by federal court rulings. That defiance has made him a legend within Christian conservative circles. But even in famously conservative Alabama, there simply are not enough Christian-sharia advocates to ride that issue into high office on a consistent basis. In 2006, Moore got just over 33 percent of the vote in a two-way GOP primary. In 2010, he came in fourth with 19 percent of the vote. On the two occasions he won low-turnout elections to become chief justice of Alabama’s Supreme Court, he underperformed his poll numbers, indicating that more than a few Republicans had reservations about supporting him when it actually came time to vote.

Christian right candidates face even greater problems at the national level. Despite Republicans’ frequent references to God, “Judeo-Christian” values, and promises to roll back LGBT rights and abortion, party elites have shown less interest in promoting social conservatives’ agenda items than in doing the bidding of libertarian billionaires seeking tax cuts and deregulation.

Mike Huckabee, the former pastor and Arkansas governor who twice ran for president as an evangelical Christian candidate, outright admitted this in a 2016 interview.

“A lot of them, quite frankly, I think they’re scared to death that if a guy like me got elected, I would actually do what I said I would do,” he said, referring to other Republicans who were vying to become the social conservative candidate that year.

Ordinarily, casting another champion of the Christian right aside for the good of the party is something Washington Republicans wouldn’t think twice about. What’s different this time is that Moore has finally managed to tap into the immense well of grassroots conservative anger at GOP elites. While there is considerable overlap between conservative populists and hardcore Christian nationalists, they are actually distinct groups on the Republicans’ right flank, with the former having no real objections to big government while the latter are traditionally eager to slash social spending.

In past years, conservative populists were much less engaged in politics; they saw the GOP as more interested in catering to the upper class and people who wanted prayer in school. Their refusal to turn out for the party’s 2012 nominee put a big dent in the Midwestern vote totals of former venture capitalist Mitt Romney.

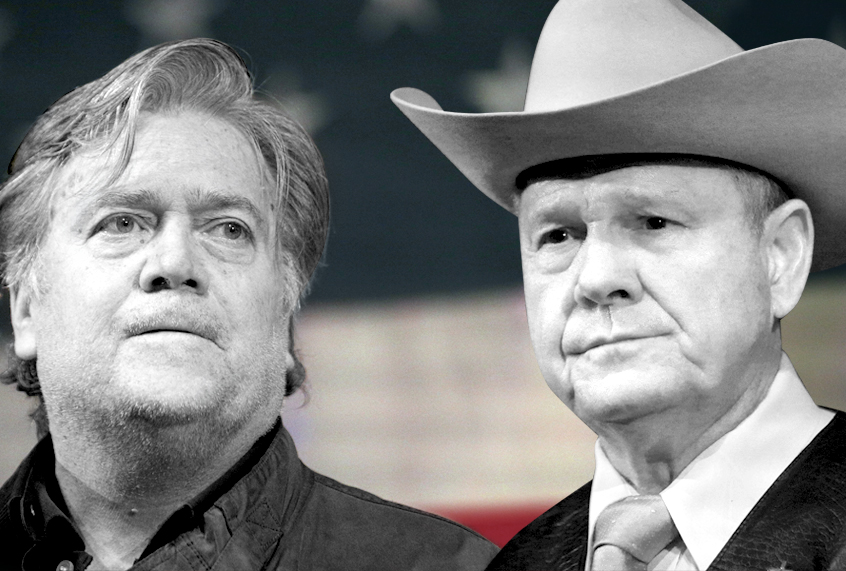

The 2016 campaign of Donald Trump managed to bring back the populists, however, as he rhetorically abandoned all of the traditional Republican shibboleths about “limited government” or “job creators.” That success was mostly due to Trump’s idiot savant grasp of politics, although his former campaign chairman Steve Bannon also was useful in this regard.

The fact that the GOP had failed to win the majority of the popular vote in five of the six presidential elections before 2016 demonstrated clearly that the old Republican alliance of foreign policy hawks, Christian nationalists and libertarians had shrunk too small to win national elections.

But remaking a party coalition is an extraordinarily difficult thing, especially given the pieces with which Trump had to work. This is in large measure because the anti-government agenda promoted by the Republican Party, beginning with Ronald Reagan, has never been popular. To win, Republican political consultants — who figured out all of the tricks of the trade much sooner than their Democratic rivals — realized that they could utilize what’s now called “negative partisanship,” uniting voters against groups or policies they despise.

Building a coalition based on unified opposition, rather than in support of a shared agenda, can be effective. But it only works for so long. The rise of the angrier, racist “alternative right” and the incoherent, conspiracy-mongering “MAGA movement” are the inevitable result of such actions.

Trump’s tenuous fusion of populists and Christian nationalists has primarily worked because, in large measure, he matches the demographic profile of the people who continue to support him. Trump is a loud brawler who constantly lashes out at scientists, intellectuals, racial minorities, immigrants, the news media and, most importantly, the Republican Party leadership.

While Trump has accomplished little legislatively, in large measure because of this vociferous style, anger is the primary characteristic that Trump, Moore and their voters all have in common. “But he fights!” has become almost a clichéd justification for supporting Trump among conservative activists. Nonetheless, it is still a frequently used phrase.

With no real policy agenda aside from a desire to restrict immigration and foreign trade deals, Trump has had to tread a difficult line with regard to his base. Republican elites like Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell correctly see that having Roy Moore in the Senate could do grave damage to the GOP’s electoral prospects. They now hope the president can bail them out by convincing the extremist former judge to abandon his candidacy.

Through statements from press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders and Attorney General Jeff Sessions (who formerly occupied the Senate seat Moore is seeking), it has become evident that Trump agrees with this analysis. But this is one of those rare instances were the bellicose president may actually tread very lightly. There are two reasons for this:

1. Trump has already run afoul of his fans in Alabama by backing Moore’s vanquished rival, McConnell loyalist Luther Strange, in two primary elections.

2. If Trump speaks too strongly on the matter, some within the White House fear it could embolden the many women who have accused the president of sexual harassment, a very real danger in the new media environment that’s been created after the exposure of the large-scale predations of former movie mogul Harvey Weinstein.

Even if Trump were to decide it was worth the risk to gently or loudly force Moore to stand aside, however, there is no guarantee that his efforts would work. Moore’s entire career has been built on defying higher authorities in the pursuit of his personal religious and political views. There is no indication whatever that he would be willing to listen.

“Only Roy Moore can rid the GOP of Roy Moore, and he’s more stubborn than five mules on a bad day,” said Quin Hillyer, a conservative columnist based in Mobile, Alabama.

There’s also no guarantee that Republican voters would listen, especially the Christian supremacist hardcore Moore has spent his career cultivating.

“As long as Moore denies the charges, I think Trump, Bannon, and most of the religious right leaders will stand by him,” said Peter Montgomery, a senior fellow with People for the American Way, a liberal group that keeps tabs on far-right activists.

“Religious right leaders trained for this when they declared Trump one of God’s anointed,” Montgomery said. “They abandoned the idea that the character of our national leaders matters when they endorsed Trump in return for his promises to make them more powerful and give them the Supreme Court of their dreams.”

Aside from an outlier poll that was released Wednesday by the National Republican Senatorial Committee, showing Moore trailing his Democratic rival Doug Jones by 12 points, public opinion surveys since the accusations began flowing last Thursday have shown Moore continuing to cling to a lead.

“I think he can still win, but it is now a slightly — but only slightly — uphill battle,” Hillyer said.

Alabama GOP officials have shown little willingness to publicly rebuke Moore for his alleged deeds, even as numerous reports have come in about his seemingly predatory or troubling conduct with teenage girls. The only major Alabama Republican to break ranks so far is the state’s other senator, Richard Shelby, who will retire instead of seeking re-election.

Republicans want to get rid of Roy Moore in the worst way, but they can’t find a way to do it because the voters who love him are too important to their electoral prospects. In a way, all this may serve as a foreshadowing of what will happen to Trump when it comes time for him to exit the political stage, willingly or otherwise. Republicans never wanted to have a former reality star as their president. But everything they had done for generations made it possible, and as a direct result of their past choices, they were unable to stop him.