We glimpse him for approximately eight seconds. There he is, the wraith in the green suit and the black shirt, and all we know of him is what the immediate future holds. As the seconds tick, he will be approached by the white man in the jean jacket, and their brief dance will result in his death.

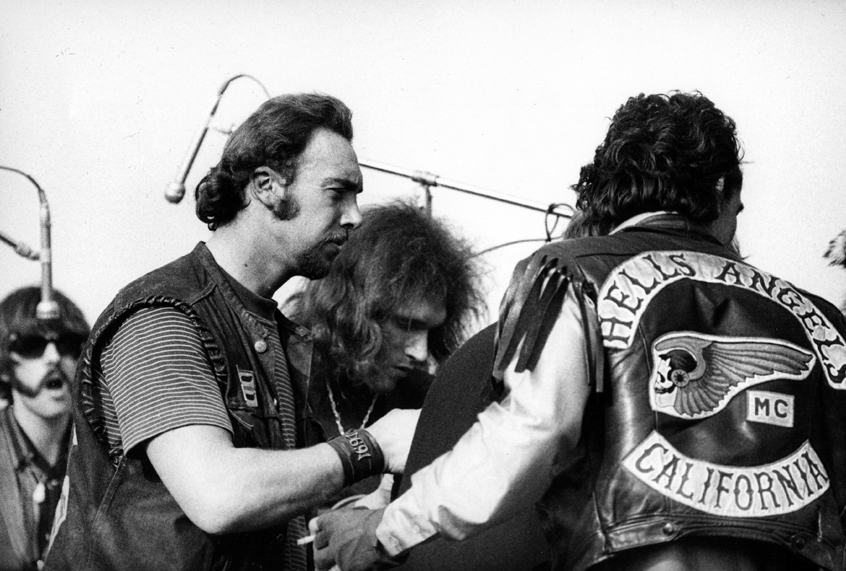

Ask any rock fan, or any veteran of the 1960s, about Meredith Hunter, and they will likely be able to identify him. He is the 18-year-old African-American who was killed at Altamont. He is, they will tell you, the person whose death, conveniently occurring in December of 1969, marked the end of the 1960s. His name inevitably prompts a discussion about the Rolling Stones, who helped plan the show, and the Hells Angels, who were hired to provide security at Altamont, and were responsible for his death. His is a story, we have been told, about music and mass gatherings and the failings of popular culture.

It was the blind spot of the counterculture that its white participants could not always see the ways in which its planned utopia was a segregated community, its spaces unfriendly or downright hostile to others. How could African-Americans feel comfortable at a concert patrolled by violent bigots who possessed a troubling record of racial and political animus, ranging from interrupting an anti-Vietnam War demonstration in Berkeley and beating protesters to attacking African-Americans who had made the mistake of approaching their San Francisco clubhouse? It was telling that the Angels’ blatant racism—something the bikers made no attempts to conceal—was never a prominent factor in the question of whether to employ them, or seek their company.

Hunter’s sister Dixie Ward remembered traveling in her husband’s truck around the Bay Area in the mid-1960s and seeing burning crosses. Long after her brother’s death, Ward would tell her children that there were corners where they could not congregate. If they were white and with their friends, they’d be chatting; if they were black, they’d be instantly approached by the police, a potential threat.

Much like today, the late 1960s were a time of heartbreaking turmoil and long-sought advances, political reaction and social progress. Lyndon Johnson had told America “we shall overcome,” and Richard Nixon had been elected his successor on a platform of racially coded “law and order.” Politics was, in no small part, an extended sub rosa debate about race, hurtling between idealistic hopes and a repressive desire to lash out at African-Americans’ demands for fairness. Meredith Hunter’s death was instantly co-opted as a rock story about bloated superstars and feckless promoters and a misguided counterculture. As much as any of those factors, though, Hunter’s death was about the places black people still could not go, even in 1969.

READ MORE: The secret to Jim James’ solo album “Uniform Distortion”

American history is, in many ways, an effort to save and reclaim the past from our collective desire to forget. The story of Meredith Hunter does not reflect well on popular music, the counterculture, or American society’s ability to fully grasp the tragedy of racism, but we must tell it so as to avoid having to live through it again.

In the aftermath of the deaths of Trayvon Martin and Tamir Rice and Eric Garner, knowing that police are regularly summoned to subdue the threat of black children selling bottles of water, or young black men visiting Starbucks for a business meeting, we have become more sensitized to the murderous double standard of public spaces, where young African Americans much like Meredith Hunter find themselves trapped in places they discover they are not allowed to be.

We live in a country where the president of the United States regularly makes use of open racial animus against African-Americans, Hispanics, immigrants, and others for political purposes. We have been through this all before, and it is incumbent that we remember all the details.

Hunter served as a symbol of the racial progress this country still had to make, his death understood by many to be a figurative end of the idealism of the 1960s. It was telling that Meredith Hunter could play that role without being granted any heft, any existence prior to the show, or his fatal encounter with the Hells Angels. He was a symbol of chaos and little more. In “Gimme Shelter,” the acclaimed documentary directed by Albert Maysles, David Maysles, and Charlotte Zwerin, Hunter is never identified by name. One of my goals in writing my book “Just a Shot Away” was to give Meredith Hunter back his life story—one that begins before cinematographer Baird Bryant turned his camera on and captured Hunter’s final seconds.

We have yet to resolve many of the questions that bedeviled the country in the late 1960s, including how we protect young men and women of color—or even, disturbingly, how committed we are to doing so. Nearly fifty years after his death, Meredith Hunter remains an unsolved question, a nagging reminder of the discrepancy between our flowery rhetoric on race and the ugly reality in the soil.