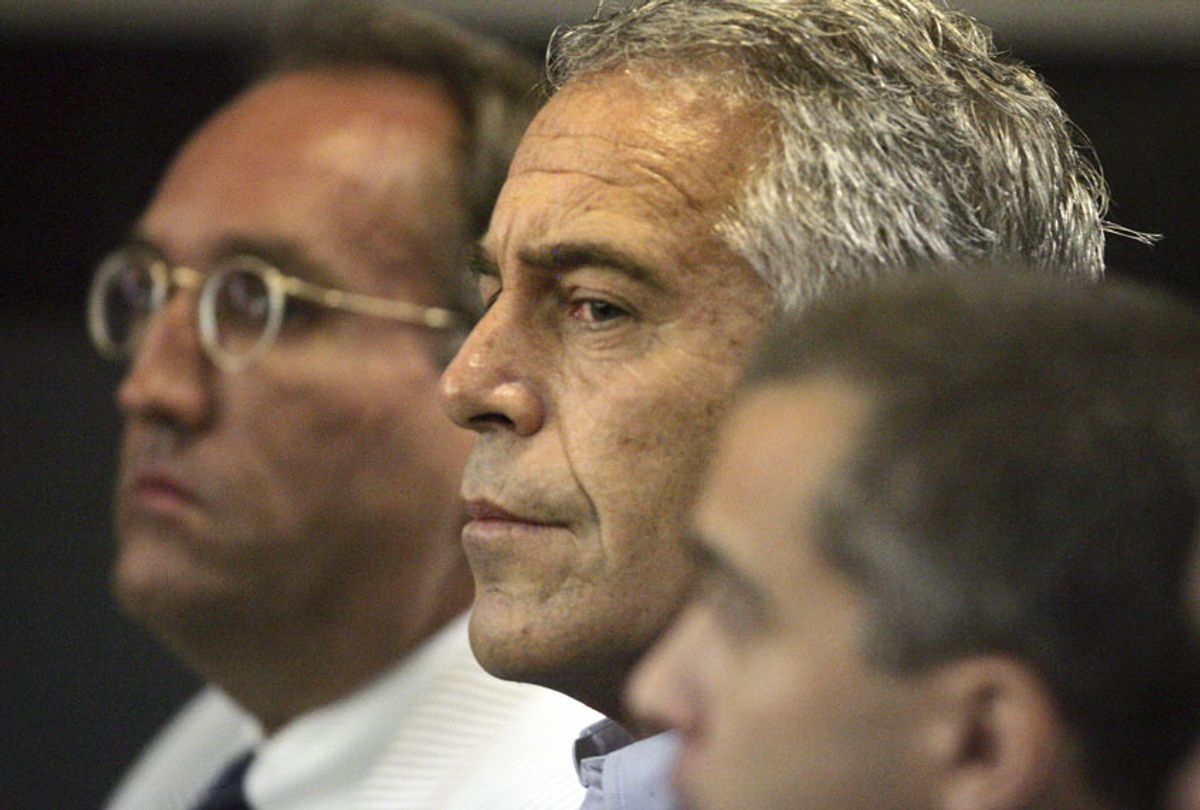

The surprise arrest of billionaire Jeffrey Epstein on Saturday — and the revival of a decade-old case against him for sex trafficking — is a big story in its own right. That's both because of Epstein's own unbelievably sleazy profile, but also because it's possible that other men who have been shielded from justice may be exposed for participating in the sexual abuse of minors. But the social implications may be even larger.

The Epstein case is a real test over whether the #MeToo movement, an explosive period in which thousands of women stepped forward with stories of sexual harassment and abuse, was just a flash in the pan. Will we see long-term changes in how our society deals with powerful men who commit sexual abuse with little or fear of consequences? Or are we moving back toward business as usual and sweeping such things under the rug?

From the moment the #MeToo movement started, both supporters and opponents suspect that it would never really have any long-term impact. A few powerful men's careers would be sacrificed and then we would return to the status quo where men of privilege can abuse and harass women (or men) without facing any meaningful punishment. With cynical speed, defenders of the status quo started workshopping talking points about how #MeToo had gone too far and helpless men were the real victims of the all-powerful women's movement. That had worked before, after both the anti-rape activism of the 1970s and early '80s and after the Clarence Thomas-Anita Hill debacle: There's a temporary burst of social condemnation of sexual abuse and then a quite retreat to the way things used to be.

Now, less than two years after the #MeToo movement went big time with the October 2017 revelations about movie mogul Harvey Weinstein, it's an open question of whether the immediate and vociferous backlash worked. Evidence that the sexists are winning is daunting. Brett Kavanaugh was confirmed to the Supreme Court, despite two credible allegations of sexual assault. That happened less than a year after the Weinstein article, creating a clear marker in the historical landscape that the #MeToo tide had been turned.

The return to the era of no-accountability has spread rapidly since then. As Rebecca Traister of New York magazine detailed in June, Republican men realized that they can avoid consequences by simple stonewalling, but it's not just them. Democratic men who've been accused of sexual misconduct — and even of rape — are starting to figure out that refusing to leave office no matter how many members of your party call for your resignation tends to work out in the long run. The sense that the sexists are winning is so strong, in fact, that a credible rape allegation by journalist E. Jean Carroll against Donald Trump barely registered in the media, largely because most pundits and editors assumed that nothing consequential would ever come of it, which is the very definition of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

But there have also been signs that #MeToo isn't as dead as the defenders of male privilege hope. Around the same time that Kavanaugh was wiggling free of consequences and into a lifetime seat on the Supreme Court, CBS CEO Les Moonves saw his career implode after more than a dozen women came forward with accusations of sexual abuse. Another top CBS executive, Jeff Fager, was pushed out alongside him. Moonves was a man of immense, seemingly untouchable power, who had gotten away with this behavior for decades. Yet in the end he was no match for the #MeToo movement and the hard-working journalists that have been sustained by it.

Epstein's case — at least until Trump was elected president — was the most iconic recent example of how much abuse a wealthy and powerful man can get away with. By the time he was arrested for sexual abuse of minors in 2008, Epstein had ensconced himself deeply in power, surrounding himself with famous and powerful friends like Bill Clinton, whom Epstein hung out with in 2002 and 2003, and Donald Trump, who in 2002 described Epstein as a "terrific friend" who liked women "on the younger side."

Thanks to Alex Acosta, who was then a U.S. attorney in Miami and is now Trump's labor secretary, Epstein got a plea deal in 2007 that makes a slap on the wrist look like the electric chair. The full details came out in a 2018 series from the Miami Herald, in which reporter Julie K. Brown exposed how Acosta allowed Epstein to escape federal charges, shield the identities of "any potential co-conspirators" and keep the details from victims, so long as he pled guilty to two minor state offenses. Epstein didn't even really serve the 18 months he agreed to, as he was kept in a private wing of the Palm Beach County jail and only stayed there at night, allowed out on "work release" for 12 hours a day, six days a week.

During an MSNBC appearance, Brown said that while she started reporting her Herald story before the #MeToo movement got launched in earnest, she also thinks "the story and my journalism benefited from the #MeToo movement because we're at a point in our culture where we're giving these cases a lot more scrutiny."

Epstein was indicted on Monday morning by federal prosecutors who appear to have been inspired by Brown's reporting to look deeper into the case. That alone is a good sign that #MeToo is hardly dead, but the biggest tests are yet to come. It isn't just a question of whether Epstein will be able to snake his way out of personal consequences yet again. It's also about whether any of his rich and powerful friends will be outed as participants in the sex trafficking ring Epstein was allegedly running.

As Brown reported on Monday, Epstein has been accused of "loaning" underage girls to his friends to sexually assault, and prosecutors say he had a robust network of assistance in running his sex trafficking operation. Brown also said on MSNBC that "there are probably quite a few important people, powerful people, who are sweating it out right now."

If Brown is right and there are other powerful people involved, then this could become a major test of whether or not #MeToo has caused permanent changes. Will guilty people be able to fling influence and money around and make their criminal behavior disappear into the ether, as they have done for years? Or will this finally be the moment that people who have gotten away with horrible sex crimes finally get what's coming to them?

There's no way to answer that right now, but the mere fact that Epstein has been indicted again offers reason to hope. The sexist backlash to #MeToo has been robust in its efforts to stuff the genie back into the bottle. But it may be harder than the counterattackers believed to erase nearly two years of public outrage, and public truth-telling, about the relationship between sexual abuse, power and money.

Shares